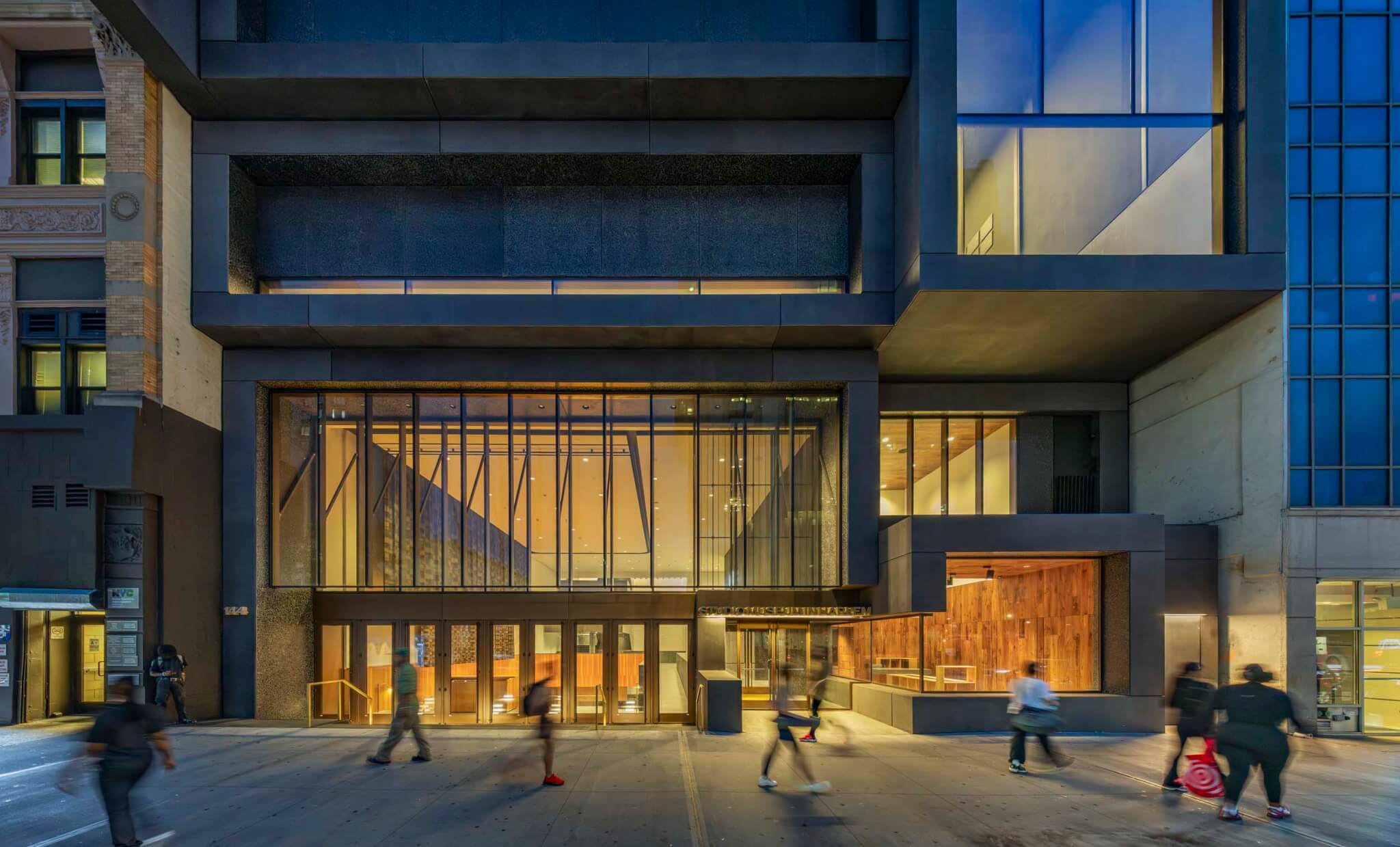

On Saturday, November 15, crowds thronged on 125th Street outside of a building faced in a series of black concrete frames. Street vendors flaunted their wares on the pavement, and music blared from portable speakers. The Studio Museum in Harlem had just inaugurated its first-ever purpose-built home, and the line to get in stretched to the end of the block: a fitting welcome for Harlem’s newest architectural landmark.

Adjaye Associates designed the new building with Cooper Robertson as the executive architect and rooftop landscape by Studio Zewde. The 7-story, 82,000-square-foot building, completed for $160 million, occupies the same site as the museum’s earlier 5-story premises, which was a former bank renovated by J. Max Bond Jr.

The wait has been significant: After the new design was revealed in 2017, the museum closed in 2018, its 50th anniversary year, for construction on the new structure to begin.

“It’s been seven and a half years, so we didn’t know what to expect,” one museum staffer told me near the entrance. “But the community really came out today.”

Rooted in Harlem

Founded as a non-collecting institution in 1968 against the backdrop of the Civil Rights Movement, the Black Power Movement, and the Black Arts Movement, the Studio Museum sought to promote artists of color at a time when they weren’t represented in museums like The Met or MoMA. In an interview conducted last December as a part of my academic research on the Studio Museum while I was a student at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, John T. Reddick, a Harlem-based architectural and cultural historian, told me the museum “evolved out of a community desire.”

Led by Thelma Golden, the museum’s longest-serving director, the Studio Museum currently positions itself as a nexus for artists of African descent. Golden, along with the museum’s board, envisioned the new building as a cultural incubator. They wanted to create a space that would reflect and expand upon the museum’s extensive history of nurturing generations of Black artists, curators, and arts administrators who have redefined contemporary art and centered Black identity and cultural production in their work.

With the new building, Adjaye Associates prioritized context. The structure was designed after considering Harlem’s architectural history, so elements like punched windows and framed doorways draw reference to the neighborhood’s distinguished brownstones. Adjaye himself told The New Yorker that he thought about the institution as a “living laboratory.”

The community desire that birthed this museum was also rooted in place. “The Studio Museum always had an identity of being on 125th Street in a central location,” said contemporary artist and educator Ademola Olugebefola. (A founding member of the Weusi Artist Collective and the Dwyer Cultural Center in Harlem, I interviewed him as a part of my academic research in March 2025.) Part cultural hub, part commercial strip, and part transit corridor, 125th Street is Harlem’s most prominent thoroughfare—and a major tourist destination. For decades, it has served as a canvas for art installations, as well as a stage for performances, rallies, and protests.

Each of the Studio Museum’s earlier premises were adapted from existing structures on 125th Street, forcing the institution to fit its vision into a makeshift vessel. The museum had a humble beginning: It first occupied a small loft space at 2033 Fifth Avenue on 125th Street. (The building has since been demolished to make way for the mixed-use Ray Harlem development that is nearing completion.) In 1982, following a brief conflict over a proposed move downtown to Museum Mile—which saw the Studio Museum’s director and a founding board member resign in protest—the museum began using the renovated Kenwood Building as its current location.

It was here that the museum started building a permanent collection, which is now among the most significant archives of work by Black artists anywhere. Working with the original bank layout, this building’s interior had “an unusual flavor,” with a main gallery and a mezzanine floor, according to Olugebefola.

Golden became the museum’s director and chief curator in 2005. She started her career as an intern at the Studio Museum, then became a curatorial fellow, and subsequently worked at the Whitney Museum for a time before she rejoined in 2000 as deputy director under Lowery Stokes Sims. In time, she and the museum’s board saw how the institution was outgrowing the aging Kenwood Building and embarked on a $300 million capital campaign to both fundraise for a new building and support future operations. During the design process, Golden and her team conducted regular presentations before Manhattan Community Board 10 and took measures to ensure a clear channel of communication between the institution and the community.

Trouble Along the Way

After construction began in 2018, there were delays due to safety concerns and the pandemic. Then in 2023, the museum was caught up in a scandal when the Financial Times published the experiences of three women who credibly accused David Adjaye of sexual misconduct.

Adjaye denied the allegations, but the museum soon distanced itself from him. Pascale Sablan, CEO of Adjaye Associates’ New York office, shepherded the project to completion. “I chose not to have a public presence,” Adjaye told me during a recent interview but then added that “the studio cannot operate without me.”

Reckoning with this is necessary in a post-#MeToo era where, as critic and AN contributor Kate Wagner wrote, those who “fund his work appear to care more about the millions of dollars already spent in architectural fees than they care to take a stance about the plight of women workers.”

Still, this persuasive evidence that has sidelined Adjaye himself ought to be understood alongside what is otherwise a triumph for the Studio Museum. Voza Rivers, chairman of the Harlem Arts Alliance, said that from its inception, the Studio Museum “was a landing location for all things visual or significant, that captured Black culture.”

The museum’s purpose matters now more than ever, as arts institutions face serious opposition across our current political landscape. Earlier this year, the Trump administration dismantled the Institute of Museum and Library Services and gutted the National Endowment for the Arts’s grant programs under the guise of cutting diversity and equity initiatives in government spending. The Studio Museum has received grants from both institutions over the past few years, and for a museum of its size, the cutbacks present a noticeable loss. A new era comes with new problems.

The Studio Museum also joins New York’s museum-building boom that has delivered new wings and projects in recent years. These include the revamped Frick Collection, the Met’s Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, and Sotheby’s Breuer Building renovation. Arts organizations in Harlem aren’t far behind. The Victoria Theater underwent a renovation that opened last year, and the Apollo Theater is undergoing an expansion that’s expected to finish next year. And at the site of the Studio Museum’s first home, the National Black Theatre is slated to open in the podium of Ray Harlem next year as well.

The Building Itself

The new Studio Museum holds its important history within an architecture that is quietly monumental. Like much of the work of Adjaye Associates, it combines geometric forms, attention to materials and detailing, and a touch of late modernist, neo-Brutalist oomph. Like most Brutalist-inspired architecture, some will detest it, and some will die on a hill for it. The new building overlooks the hulking form of the Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office Building—where a portion of the Studio Museum office relocated to during the building’s construction—a kindred spirit from a bygone era.

But whereas the State Office Building stands at the center of a vast plaza, the Studio Museum fits snugly between a Beaux Arts building with arched windows to its left and a gridded glass cube to the right. The through-block structure is a bit taller than its neighbors, and its front facade features an irregular stack of rectangular black, precast concrete boxes, variously big, small, upright, prone, protruding, and recessed. Hoisted above the entrance, David Hammons’s African American Flag (1997) proudly sways in the wind once again.

Glass doors line half of the museum’s ground floor, allowing pedestrians to peer into the building’s “reverse stoop,” a multipurpose performance space clad in caramel-colored engineered wood that cleaves through the floor down into a multipurpose space in the basement. The idea emulates, and inverts, a key social element of Harlem’s brownstones. This space is free to use, even for those who don’t buy museum tickets, but how accessible it will actually be in practice is another question.

The steps resemble church pews; Adjaye Associates described the stoop’s scale as mimicking the interiors of local congregational spaces. In a theatrical flourish, the space can be ringed off from the rest of the interior by a tall, patterned curtain. The steps bring much-needed warmth to an otherwise oversized, awkward, cavernous lobby area, but some of their detailing falls short: Like most pews, they’re not particularly comfortable to stretch out on.

Upon arrival, the lobby can feel stifling, a hint that this new building is more about institutional grandeur than delivering quality gallery space to see art. The neon lettering of Glenn Ligon’s Give Us a Poem (2007) illuminates the area above low, dark walls that direct you toward the ticket counter. Adjaye explained that “the idea is to disorientate you from your traditional perception of a museum immediately. It is not a white box privileged space.”

Throughout the building, Adjaye Associates remixed the white cube with results that alternate between stellar—using signature materials like polished concrete, metallic gold accents, terrazzo, and ample wood paneling—and dully benign. Mabel O. Wilson, professor of architecture at Columbia GSAPP, noted the new building allows the Studio Museum “to have a more coherent visitor experience,” instead of a “series of additions and additions.” At the very least, such continuity means that the museum’s incredible collection is no longer confined to piecemeal galleries; it can spill out into areas like the atrium, which is the illuminated core of the vertical museum experience.

Mezzanines overlooking this void are important gathering spaces. A terrazzo-clad staircase with extra-large landings zig-zags between them, connecting exhibitions across floors. Part of the museum’s mission was to make art and artists more accessible to audiences.

Mesmerizing, minimalist light sculptures by the African American artist, activist, and organizer Tom Lloyd, feature among the new building’s inaugural exhibitions. A handful of his pieces are installed in a vaulted gallery on the second floor meant to evoke a sanctuary-like feeling. (The exhibition design is by AD—WO.) This too is a throwback: The museum’s first show, Electronic Refractions II, in 1968 was by Lloyd.

The fourth floor includes a workspace for the museum’s Artist-in-Residence fellowship, which is a key part of its mission. Artists like David Hammons, Valerie Maynard, Julie Mehretu, Kerry James Marshall, and Wangechi Mutu, all participated in the program. Currently, ahead of the next cohort of artists joining in 2026, the space is populated with more than 100 new works on paper, all from residency alumni.

To Be a Place, a visual timeline on the sixth floor, showcases the museum’s history through archival documents, photographs, and other ephemera. These materials chronicle the Studio Museum’s penchant for discovering and showcasing the varied artistic imaginations of the African diaspora.

The upward journey of ascending through the museum culminates in its rooftop space. As I stepped on to the Studio Museum’s terrace, I appreciated Studio Zewde’s plantings and stoop-like seating, set in front of neighboring water towers. But I also saw the State Office Building to the north and the glittering lights of Midtown Manhattan’s skyline to the south. At that height and in that place, the world beyond felt both endless and within reach. Within this tumultuous world, the Studio Museum has succeeded for a reason: It has continually persevered, breaking through the trammels of convention that dictated what artists and art museums could or couldn’t do. It is fitting that the pyramidal skylight above the atrium has been named the Thelma Golden Light Well: The Studio Museum illuminates Black excellence.

Jerry Elengical is a journalist who has covered art, design, real estate, and politics for STIRworld, The Intercept, and City Limits.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper