In Minneapolis, where I live, two months of occupation from federal agents have changed how residents can use their city. In my own building, roughly one third of the residents are East African. Two upstairs neighbors, who are sisters, have disappeared for the last two weeks. We think they may be staying with relatives in the suburbs.

Another neighbor, who is Panamanian, works as a Spanish translator at a hospital. She has been on furlough from work for several weeks because none of the Spanish-speaking patients are coming in anymore; they don’t arrive for scheduled appointments, checkups, or even emergency care.

At one of my favorite coffee shops in the Longfellow neighborhood, employees now stand by the door, unlock it when customers arrive, and then re-lock it once they’re safely inside. The reason is that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) personnel tend to show up in surges, and they don’t bother asking permission to enter. Recently, they tried to swarm the Ecuadorian consulate in Minneapolis, a blatant violation of diplomatic protocol. The staff struggled to lock the door on them, a blatant violation of diplomatic protocol.

Such repeated incidents confirm ICE’s disregard for private, public, and diplomatic spaces, in addition to the violence they’ve brought to our city.

Why the Twin Cities?

On December 1, 2025, the Twin Cities became the latest site of ICE’s occupying forces, who arrived in the wake of an alleged fraud scandal. There were other reasons: We have long been sanctuary cities and are among the most liberal in the country. And then our governor Tim Waltz rose to national prominence last year by repeatedly noting on television how the GOP was “weird as hell”—namely, candidates Trump and Vance. It must have struck a chord.

We are also relatively small cities: We are the 15th largest metropolitan economy in the country with an immigrant population of feasible size that the still nascent ICE forces could fully terrorize with about 3,000 agents. The combined police forces of Minneapolis and Saint Paul are less than half of that. The combined police forces of Minneapolis and Saint Paul are less than half of that.

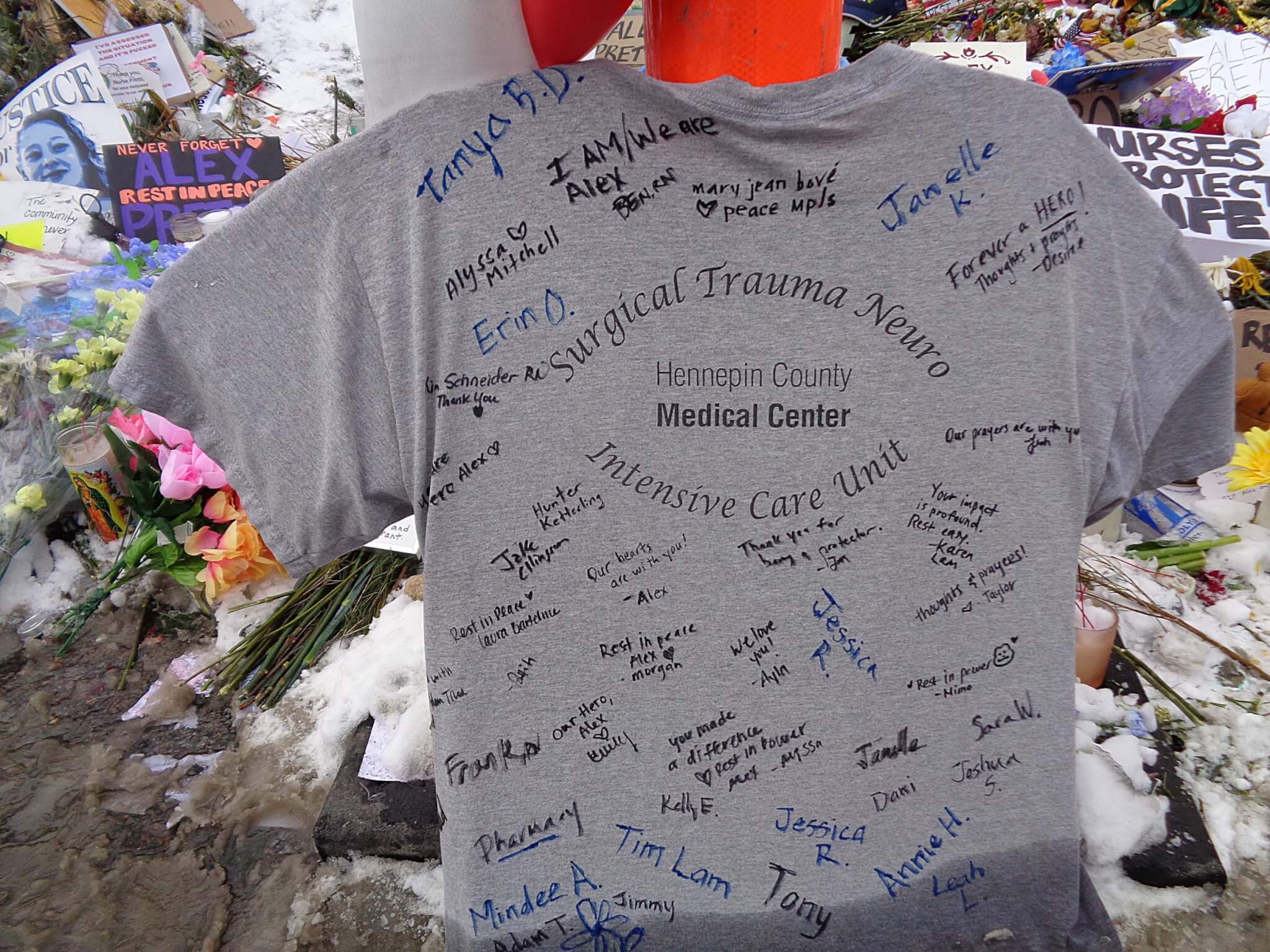

Uncertainty was the first local reaction, then resistance. But after the January 7 murder of Renée Nicole Good, Minneapolis and Saint Paul exploded in protest. We had not seen anything like that since George Floyd was murdered in May 2020 by the Minneapolis police. Last month, the situation intensified after Alex Pretti was shot and killed and video evidence clearly showed how the official narrative of the encounter was a lie.

Rather than a singular act of streetside cruelty, ICE’s masked forces appear in many places with unclear motives. This occupation is not a singular event but an onslaught of attacks. This has changed how we move around the city. Kids are held home from school, and neighbors band together in ICE Watch groups, complete with improvised checkpoints. We watch the news or stay updated on an app like Citizen to make sure nothing is happening where we plan to go.

Whereas the murder of George Floyd occurred in late May during one of the most beautiful months of the year, the ICE occupation is happening in one of our coldest winters in a decade. Color has receded from the city. Dirty snowbanks line the streets encrusted with ice—the frozen water kind—thanks to previous freeze-thaws.

There is too much road salt everywhere, on sidewalks, on streets, inside buildings and our homes. Now a new element joints this bland palette: the ICE agents themselves in their beige protective vests, black and brown skin-tight masks, baggy utility pants, and camouflage. Together, they move in cordons and can show up at any place at any time.

When they arrive for an “action,” the large and anonymous officers pour out of their trucks and fan out along the street as a core team rushes to the homes and businesses of planned targets. The outer perimeter is intended to keep back the protesters who rapidly arrive thanks to their online alert networks. They follow ICE movements and actions as they unfold across the city.

Three Types of Responses

From what I’ve observed, there are three main types of anti-ICE protests that bring people to the street. The most visible in the national media are the marches and gatherings of tens of thousands of people in downtown streets and government plazas.

The second version engages people like me, who drive by, see a protest on a bridge over the Mississippi, and stop. Someone gives us a sign that reads ICE GET OUT! or similar. We stand there for 20 minutes or maybe an hour. The fact that it might be 10 degrees doesn’t seem to deter people. I hadn’t been planning to do it, but the first time I stopped, I found the enthusiastic honking of cars passing by so restorative. At least we were doing something. We were not alone, and most people liked us for it. I attended one rally where the parents of a local elementary school organized a bridge protest and brought their children along.

The third variant are the boldest and bravest protesters who mobilize when ICE arrives. This happens quickly thanks to the communication networks of the dedicated activists, also known as the “commuters.” These are regular Minnesotans who have interrupted their own to patrol the streets, notifying neighbors about ICE presence and observing ICE interventions. Their ranks are made up of everyday people, they are nurses and doctors, teachers and parents, faith leaders and their congregations.

Both Renée Nicole Good and Alex Pretti were killed because they were in these situations. Good was attempting to leave the area in her car, and Pretti was an observer with a cell phone in hand to document live actions by federal agents. (A VA nurse, he sprang into action to help a woman being accosted by agents before they turned to him.) Ironically, it was the multiple handheld cell phone videos that deconstructed the horrible details of their deaths. Similarly, in 2020, it was the cell phone video taken by a teenage girl that proved the total and unnecessary cruelty of Derek Chauvin’s killing of George Floyd. Cell phones have changed the way citizens and law-enforcement agents operate Minneapolis.

But today’s federal agent-occupiers don’t seem to get the message. They’re supposed to wear vest cameras, but apparently do not use them. They should have direct footage of each of the murders, yet videos and imagery have yet to be shared. State and city enforcement investigators were not allowed to collect evidence of the scene. This is a case where the federal government is seeking to control state and municipal spaces along with the narrative of what actually happened.

On the Ground

Lately, there are marches almost daily in my neighborhood. I had the odd experience of seeing my building in the background of a Japanese newscast. As a backdrop to these actions, the neighborhood takes on a sense of remove, a distance that makes one begin to see their own home in a different light. We are both inside and outside, well aware of every detail at the scene, yet seeing it from afar, augmented through social media. For white citizens like myself, we have choices about how we engage. We can go to bridge protests with little fear of arrest or being sent to a detention center in Texas.

It is very cold here right now. When the temperature hovers near zero, more than four minutes of skin exposure can lead to frostbite. So when we see an elderly Hmong man being dragged from his house with nothing but his Crocs, boxer shorts, and a blanket slung over his shoulders, we know the stinging, electric cold he must be feeling on his exposed chest, arms, and face. Different people are haunted by different images. This is the one that most haunts me. I empathize with his physical pain but will never fully know his fear of what comes next.

For me, the most anxious moment happened on Saturday, January 17, when pardoned January 6 rioter Jack Lang planned a white supremacist rally in the park west of the Hennepin County Government Center. From there, he planned to march to Cedar Riverside, the largest concentration of Somalis outside Mogadishu. On the other side of the building, anti-ICE forces planned a competing rally. Everyone knew about this.

My neighbors stayed inside as helicopters flew overhead. And then the news came that the ominous and threatening pro-ICE protesters were actually running away to their hotels, chased by the anti-ICE protesters from the neighboring plaza who vastly outnumbered them. They never got to burn the Quran as they intended, and it soon came out that there were probably fewer than 50 of them. Despite their macho bluster, they looked absolutely pathetic.

ICE is also visiting outer suburbs and greater Minnesota. On January 14, a group of agents had lunch at a Mexican restaurant in Willmar, a diverse community thanks to the workers who work in the area’s meat, poultry, and edible oils processing plants. In the afternoon, they came back and arrested some of the workers in the restaurant who had served them.

Yet, there are some public places, events and gatherings where the spirit of resistance can emerge. On January 23, a group of pastors protested at MSP airport, moving out into the passenger pickup lane and momentarily kneeling on the pavement. They were asking major airlines to condemn ICE deportations, roughly 2,000 of which had already gone through MSP. I heard a first-hand account from one of them describing how they wrote their phone numbers in ballpoint ink on their right forearms should they need to be identified later.

Singing Resistance

On Saturday, January 24, over 1,000 singers converged at Hennepin Avenue United Methodist Church with only a few hours’ notice. Having outgrown their planned venue, they asked the church for help. The church planned for 950 people; 1,400 showed up.

Elizabeth Macauley, Hennepin’s pastor, along with a leader of Singing Resistance, soon appeared on CNN with Anderson Cooper to share how this now-viral event happened and what it says about life in the Twin Cities. With its soaring, needle-like spire, Hennepin Avenue Methodist is one of Minneapolis’s great landmarks, modeled on the French-English gothic of Ely Cathedral. Designed by one of our great legacy firms, Hewitt & Brown, it is arguably the most beautiful church in the Twin Cities.

But on that frigid day, it was not the architecture that drew people in. Rather they came to to be together, to hold candles and join in song. Their voices rang out. This public space gained sacredness not as a work of design, but as vehicle for people called to share an expression of pain, community, and hope.

Frank Edgerton Martin is a landscape historian, architectural writer, and design journalist. His writing on campus planning, suburban history, design, and landscape preservation has appeared in publications including: Architecture, Perspecta, Modulus, Fabric Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Design Quarterly.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper