The Type V City by Jeana Ripple | University of Texas Press | $45

In the aftermath of the Great Fire of 1871, Chicago faced a fateful decision on how to rebuild. City fathers and business elites supported a citywide fireproof construction mandate. On the other side, the city’s working class wanted to preserve its ability to build cheap wooden homes in peripheral neighborhoods.

In the end, Chicago adopted a compromise that set “fire limits” in and around downtown, establishing areas where fireproof building materials would be required. Wood construction would be permitted in outlying areas.

In the decades following the Great Fire, downtown Chicago would become a center of architectural innovation, serving as the launchpad for the skyscraper. The city’s suburban-style residential neighborhoods would become engines of upward mobility for millions until the late 20th century, when whole blocks of wooden houses were so physically and economically distressed that they would be razed to the ground.

Did building codes play a role in this historical arc?

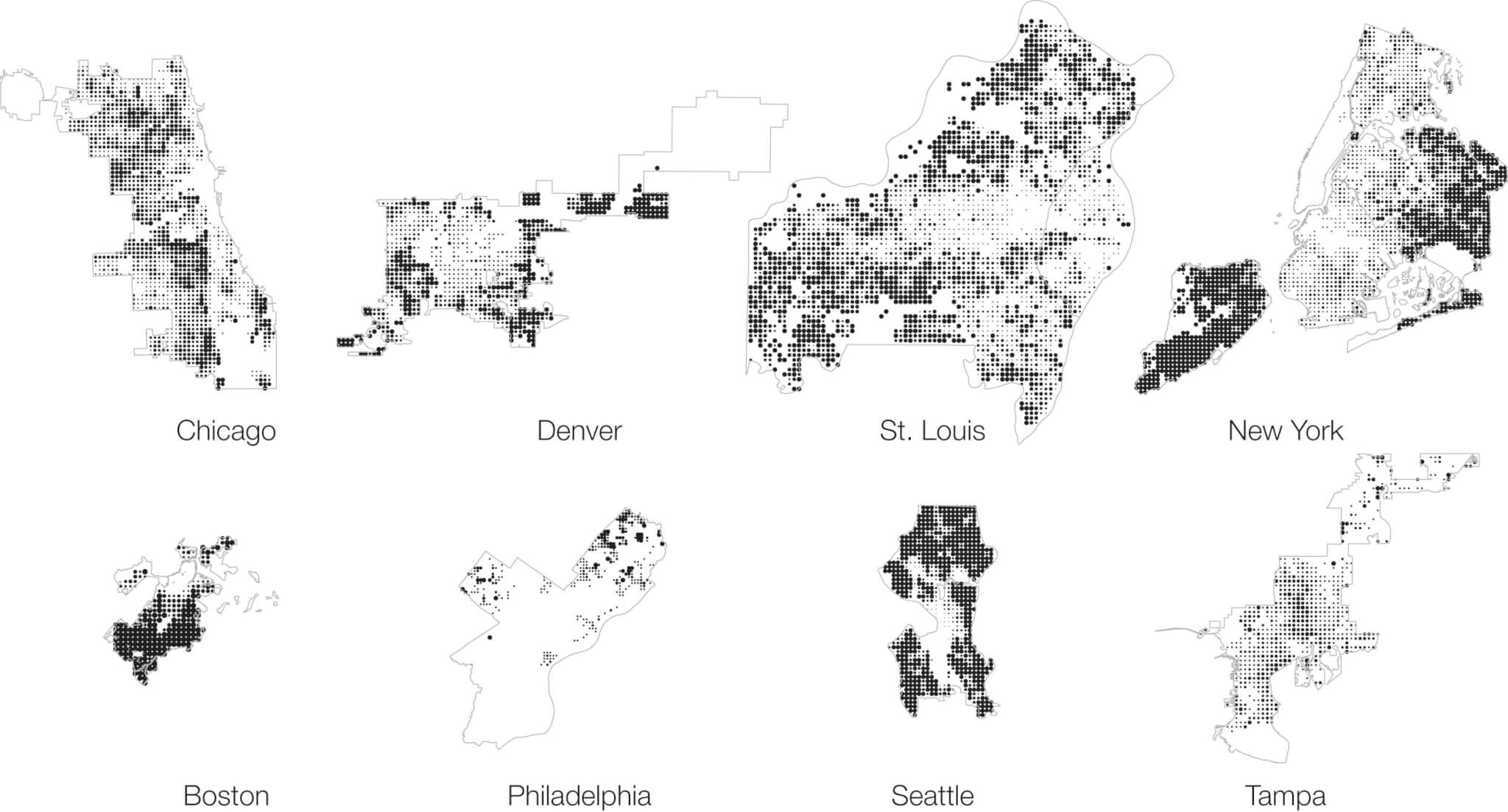

That’s one of the central questions animating The Type V City by Jeana Ripple, a professor of architecture at the University of Virginia. Ripple examines how the spread of wood-frame “Type V” buildings shaped the economies, social relations, and well-being of five American cities: Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, Tampa, and Seattle.

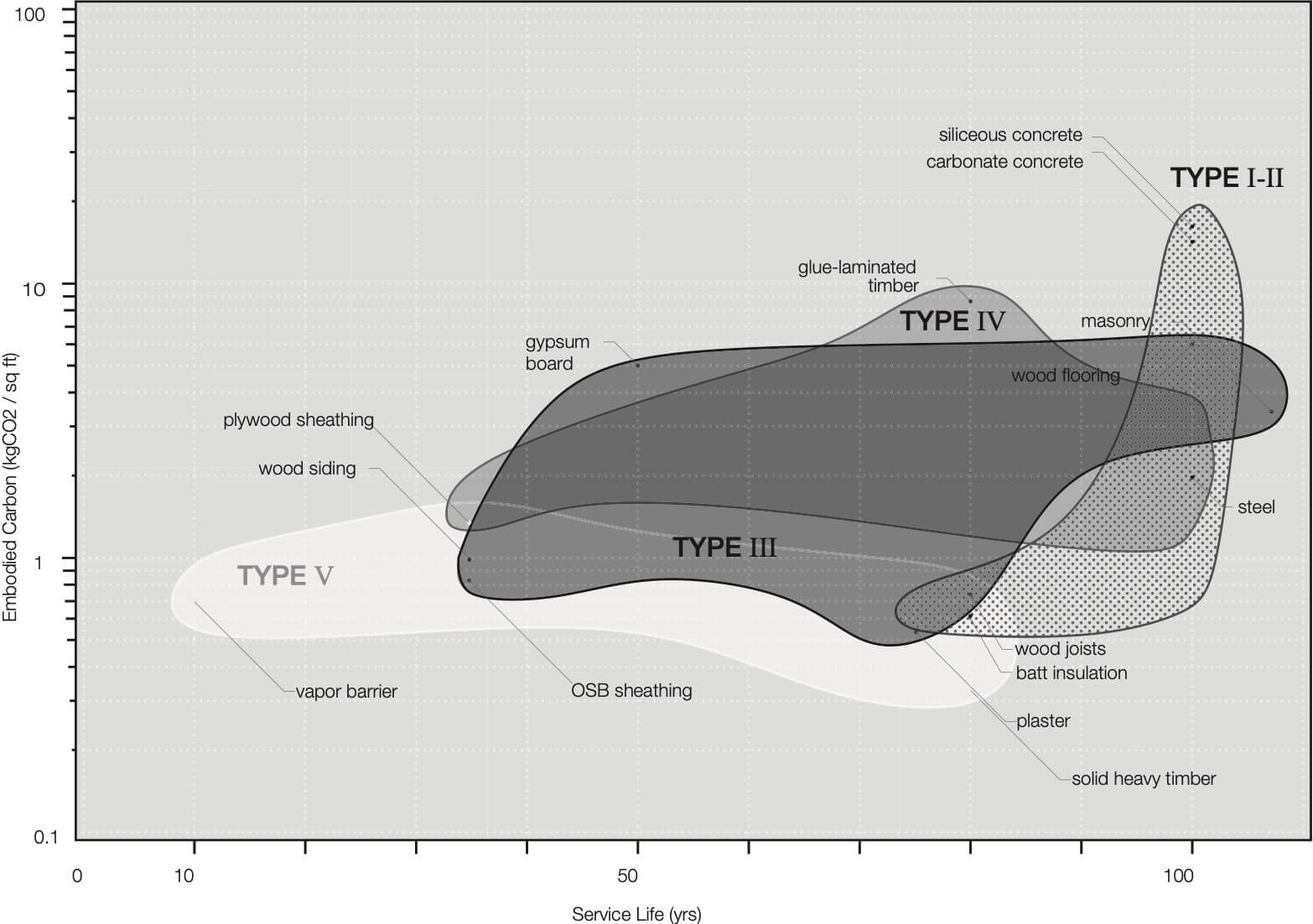

Chicago’s 19th-century codes set the precedent for the major building materials categories, ranging from Type I, totally fireproof concrete or steel to Type V, light timber and other combustible materials. In today’s International Building Code, Type V is clearly dominant: 92 percent of new single-family homes and 85 percent of new multifamily homes in the United States use these materials. While American building codes have largely done the job they were intended for, with their narrow focus on fire risk, Ripple shows how they have failed in other regards.

Type V City arrives at a moment when building codes are receiving greater scrutiny in policy circles. Archaic regulations are being reevaluated in the midst of a crushing housing crisis and a popular revolt against the aesthetics of contemporary apartment design. Ripple’s case studies provide insight into the myriad ways building codes affect the form and function of cities.

The competition between two priorities—affordability and durability—is a major theme throughout the book. Ripple’s vividly rendered spatial analysis shows that Type V neighborhoods in Chicago were historically both more likely to be redlined and to see abandonment and demolition than neighborhoods of brick buildings. That could be a product of the higher maintenance costs and quicker rate of deterioration of wood structures as compared with masonry.

Ripple acknowledges that there were many other socioeconomic forces that contributed to these spatial and racial disparities beyond building materials. There are, after all, plenty of well-maintained, well-functioning wooden houses across Chicagoland and beyond. But in other cases, the consequences of building material choices are even more clear.

In her New York case study, Ripple tackles how building codes have perpetuated disparities in environmental health. The city’s 1916 zoning code mandated masonry throughout most of the metropolis, but allowed wood construction in its “suburban limits,” the as-yet-unbuilt areas stretching along the coastal plains of southern Brooklyn, eastern Queens, and Staten Island. The consequences of this decision were stark when Hurricane Sandy roared through. Ripple reports that a full 99 percent of “red-tagged” buildings, those deemed unfit for habitation, were Type V structures. In some of the buildings left standing, residents began complaining of “Sandy Cough” or “Rockaway Cough,” as the molding wood of their houses sickened them.

Ripple also delves into how labor unions have leveraged building codes throughout urban history. Unlike Chicago and New York, Philadelphia historically required brick or stone construction throughout virtually the entirety of the city. However, the impetus here was not fire risk. Brick mason unions fought for these rules to be codified in order to preserve high-skilled, high-wage jobs on masonry construction sites. At the same time, they also limited access to those jobs from the city’s communities of color. In Philadelphia, the brick masons were, and still are, as Ripple shows, a white man’s club. The city’s building codes were therefore directly connected to the perpetuation of employment segregation and racial inequality.

In other cities, building code enforcement became an instrument for displacing Black communities from centrally located neighborhoods during urban renewal. Ripple recounts how in Tampa, the many wooden houses in the Central Avenue neighborhood were used as a pretext for mass demolitions. Black neighborhoods in Tulsa and Charlottesville were razed under similar auspices.

Among Ripple’s case studies, one city stands out for its commitment to wood construction. In its early pioneer days, Seattle, the nation’s timber capital, stuck with wood construction even in the wake of devastating fires. In more recent decades, it has also been a Type V construction innovator.

It was there, in the 1980s, that chief building officer William Justen recognized that state codes would allow multistory Type V buildings to rise above one- or two-story Type I concrete podiums. Thus, the infamous 5-over-1 was born. In 2015, the International Building Code adopted up to five stories of Type V construction above a single story of Type I, enshrining the 5-over-1 as the default apartment typology of our time.

Ripple is concerned about the longevity of 5-over-1s, which now make up a large majority of new apartment buildings, given wood’s propensity to expand and contract. She also decries their lack of adaptability to new layouts and uses, due to their large number of immovable structural columns.

Yet Ripple has little to say on the most common criticisms levied at 5-over-1s: that they’re aesthetically uninspired and perpetrators of gentrification. She likewise glosses over promising improvements on the horizon for the apartment typology du jour, even though it would fit quite nicely in the Seattle chapter.

Only briefly does Ripple mention mass timber, also known as Type IV construction. In 2018, Washington became the first U.S. state to legalize tall mass timber buildings, kicking off a trend that has spread nationwide. This engineered wood technology could offer many of the same efficiencies as Type V construction, with better longevity and fire resistance.

Ripple also neglects the “single-stair” movement, advocating for the legalization of European-style apartment designs in U.S. building codes. Many of the complaints levied at 5-over-1s—including their bulk, monotony, preponderance of studios and one-bedroom units, and lack of natural light—are connected to the dual-stair requirement in U.S. building codes. A single-stair design, by contrast, allows for more exterior faces and multibedroom units, more dynamic architectural possibilities, and less wasted corridor space.

Single-stair buildings have been legal in Seattle under limited circumstances since the 1970s, and in 2023, legislators passed a law that will permit a greater variety of single-stair buildings statewide beginning as soon as next year. Other states are following suit as more research comes out showing this design is safe.

Perhaps not since Chicago’s Great Fire have building codes been so contested, yet Ripple is surprisingly silent on some of the most salient building code debates of the present day. Nonetheless, her book provides valuable historical context for the origins and impacts of these codes, including lessons that will be of value to today’s building code reformers.

Benjamin Schneider is a freelance journalist covering all things urbanism. He is the author of The Unfinished Metropolis: Igniting the City-Building Revolution.

This post contains affiliate links. AN may have a commission if you make a purchase through these links.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper