Incorporating Architects: How American Architecture Became a Practice of Empire

Aaron Cayer

University of California Press

$29.95

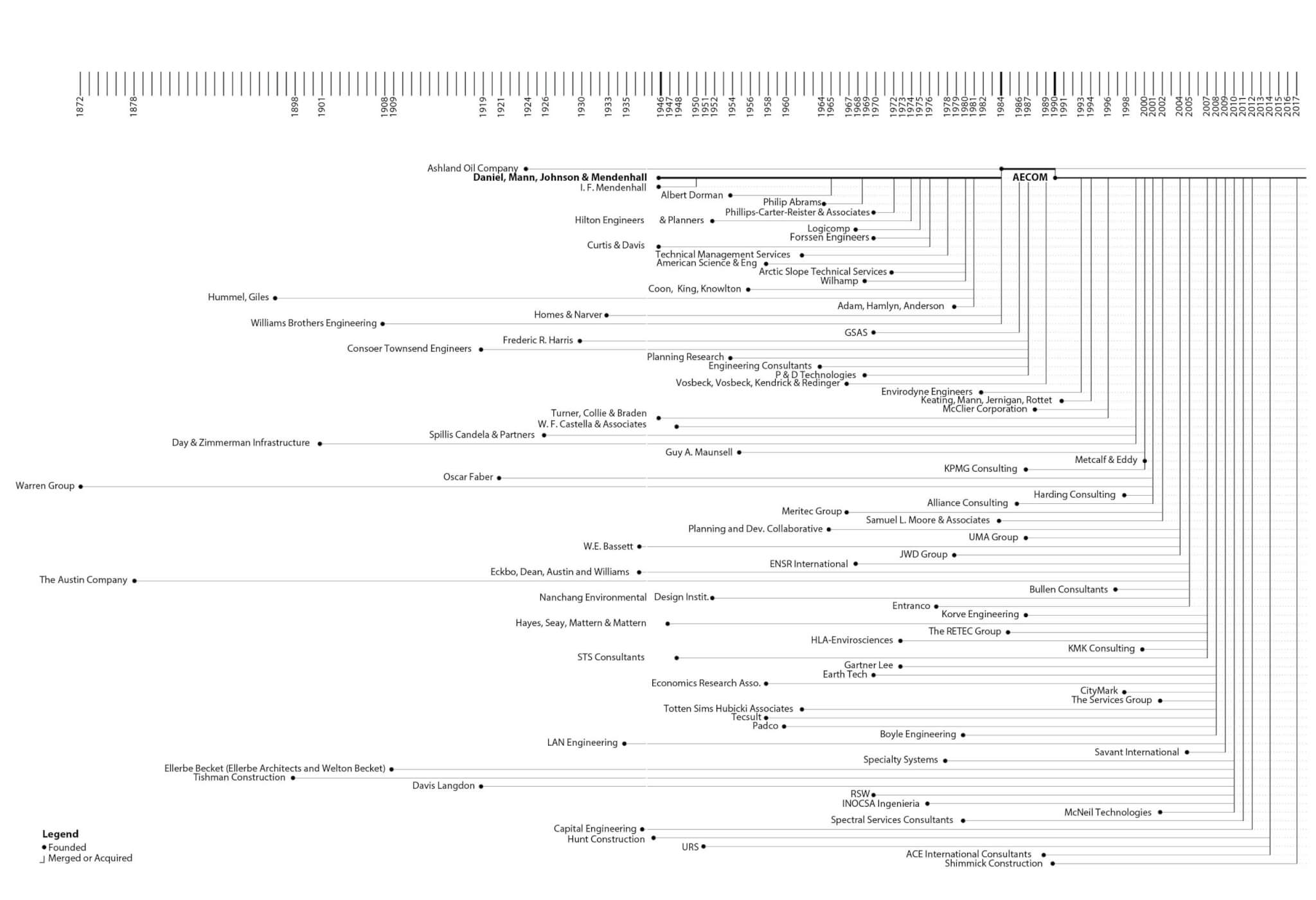

Many books pose the question: What can architecture do that’s good? Not enough ask what architecture can do for evil. Historian Aaron Cayer’s book Incorporating Architects: How American Architecture Became a Practice of Empire does exactly that. The book traces architecture’s role in postwar and Cold War American imperialism through the history of Daniel, Mann, Johnson and Mendenhall (DMJM), the firm later known as AECOM. Often viewed by critics and practitioners as a shadowy behemoth whose role blurs the line between an architecture and engineering firm and a defense contractor, AECOM is the biggest such firm in the world, with its thumb in seemingly every pie, including less savory ones such as inquiries into the reconstruction of a post-urbicide Gaza and water infrastructure for the now-beleaguered NEOM megaproject in Saudi Arabia. Were—one will learn in Cayer’s book—it ever thus!

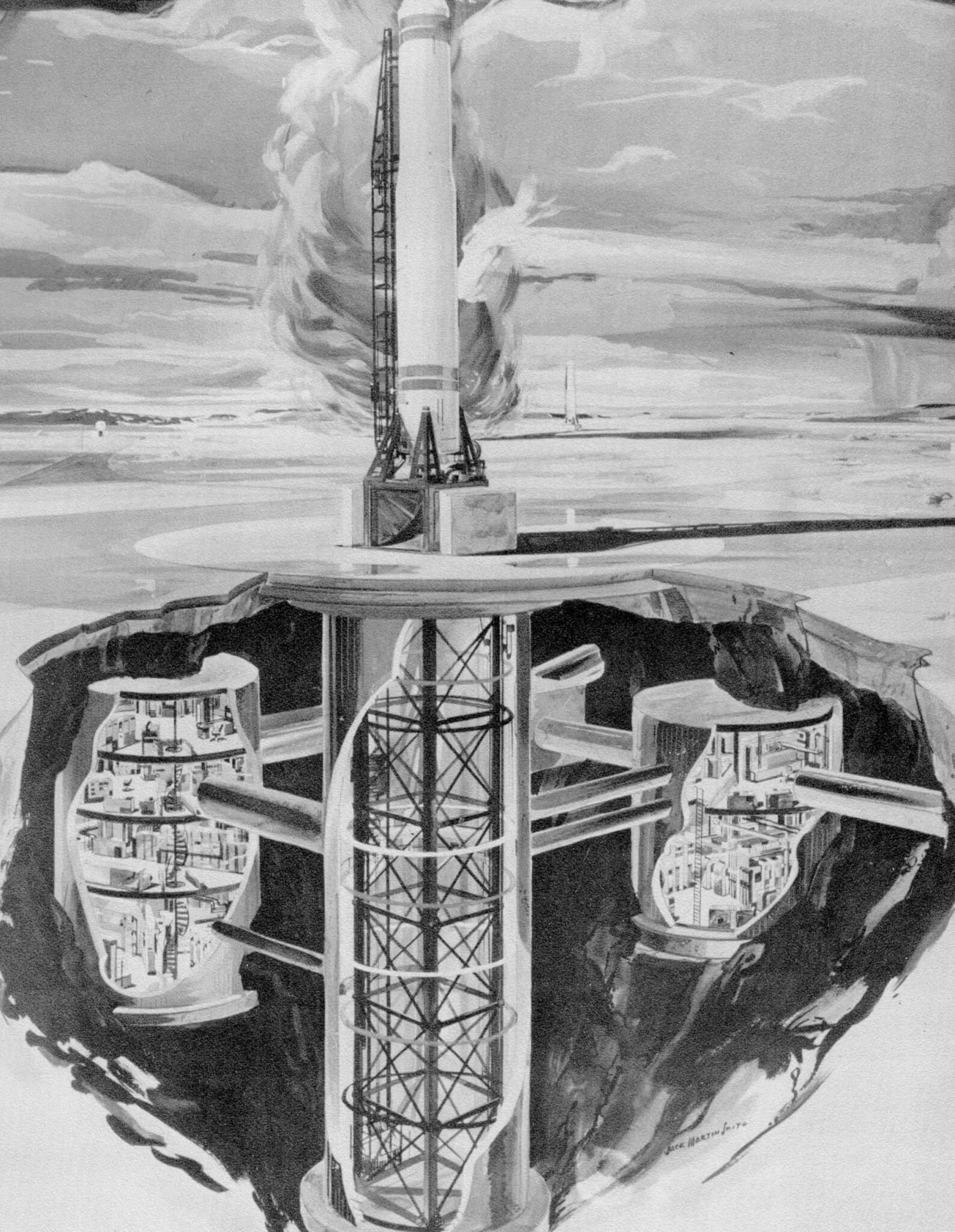

Did you know, for example, that DMJM was implicated in the Watergate scandal? And in the Jakarta program that saw the extrajudicial killing of civilians under the guise of rooting out communism? Did you know that its relationship with the Saudis goes back to the 1970s? Or that DMJM bought a warplane and refurbished it with surveying equipment that would later be used in the construction of U.S. air bases abroad? Or that it was, for a time, bought out by the Ashland Oil company, which sought to use its geospatial services for oil production? Did you know that it did a building for the CIA? That it stored its records in the Iron Mountain underground fortress? Did you know that the funding for such imperial projects was often underwritten by the construction of schools and public infrastructure for the City of Los Angeles?

Cayer, an assistant professor at Cal Poly Pomona and a longtime critical voice with regards to the labor of architecture (he is also a board member of The Architecture Lobby) is well suited to the task of linking architecture and empire. Here he offers insight into a murky world that’s difficult to historicize simply because, for matters of national security, it’s difficult to access. This makes Incorporating Architects not only a history of a firm but an object lesson on how to assemble a historical narrative through pieces of information—letters, interviews, news clippings, FOIA requests, etc.—obtained beyond an elusive central corporate archive. Helping Cayer along, however, is the role of famous architects, which itself does not go unnoticed. While he’s always been pegged as a corporate architect, there are passages in this book where César Pelli, who got his start at DMJM in the 1960s doing office parks for defense contractors, sounds like Karl Rove.

Incorporating Architects does the field a great service by demonstrating the staggering extent to which firms like AECOM were embedded within the state and thereby complicit in war profiteering, espionage, and foreign policy. It also shows how changes in the nature of work and the evolution of business models to adapt to new economic realities—i.e., the expectation of economic downturn after the postwar boom—both reinforced the appeal of government contracts as a stabilizing factor and enabled firms to adapt to and exploit a post-Fordist world through changes in their very structures. These changes were even helped along by the AIA, whose 1970s reforms liberalized (in the Reagan sense) the business side of architecture, taking what was once a “gentleman’s profession,” a trade bound by a shared, ostensibly apolitical culture and a set of ethics, and reshaping it in the image of management consultants and mergers and acquisitions.

AECOM, here, is an object lesson in a bigger claim, namely the overarching role of incorporation and conglomeration on architectural form, ethics, practices, and business. Cayer writes: “While adopting the terms, tools, and techniques of the state, architecture and engineering firms produced and made visible the stages of capitalist development through the design of their firms and of everyday urban infrastructure.” This claim is substantiated throughout the book’s six chapters. These respectively tackle the major structural changes in architecture firms as businesses after World War II; the history of conglomeration, especially at DMJM; how the firm’s inner structures of center and periphery, core, and subsidiaries map onto the architecture it built; the history of architecture firms within the military industrial complex writ large; concurrent publications about architectural practice; and the culture of secrecy that emerged around architectural work in the postwar era, with a special focus on the hidden work of women in computation and archiving.

Of these chapters, the front three are most compelling to the general reader, though the back half of the book has much to offer those more interested in critical interpretation and historiography. Compared to most academic histories of architecture, Incorporating Architects is very readable and at times even feels like a spy thriller. Through its studying of large architecture firms as businesses having a vested interest in their own self-perpetuation—interests that, for AECOM in particular, are intertwined with the maintenance and construction of American hegemony— architectural production is stripped down to its political and material bolts. The mechanism of stability in an unstable world was, as implied by the title, conglomerates, what Cayer defines conceptually as “firms with many firms within them—as social, physical, economic, political and technological infrastructures through which land, money, people, resources, materials, or business flow in or out and change over time.”

As for the architecture itself, while it’s always tempting to attach politics to form willy-nilly, especially with regards to the emergence of postmodernism and the corporate headquarters big firms like DMJM were producing in the 1960s and ’70s, Cayer avoids this trap, even in his critical analysis of the buildings themselves (in particular Cesar Pelli for DMJM’s Teledyne headquarters), by pairing organizational objectives with architectural thinking. “The building,” Cayer writes of Teledyne, a sprawling, horizontal structure defined by the mirrored skin made possible by Pelli’s inventive use of inverted mullions, “quite literally took on the form of an organization chart transposed onto the ground, thereby maintaining the modernist relationship between form and function while also recognizing the difficulty of designing for a future building that did not yet exist.” This is my favorite part of the book, in part because it disrupts the typical postmodern analysis—from Jameson to Jencks—of the slick-skinned buildings as ones that, to paraphrase Cayer, represented postmodernism in “their engagement with language and their abstracted relationship to capital” rather than produced it.

Overall, Cayer’s book fulfills many objectives, all of which should be considered crucial for understanding the role architecture plays in the bad infinity, as Adorno put it, of the world we’ve made. It examines in detail structures of labor and bureaucracy; exposes relationships between what is ostensibly “an art” and military and political power; and interrogates how architecture as a practice portrays, theorizes, and reproduces itself. After all, conglomeration remains a crucial way to conceal corporate structures and funds, to plan for future contingencies, and to offset liability. It continues to shape architectural practice and culture, even in “bespoke” firms like SHoP and Gehry Partners. In other words, there’s a little AECOM in a whole lot of architecture.

Kate Wagner is the architecture critic at The Nation.

This post contains affiliate links. AN may have a commission if you make a purchase through these links.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper