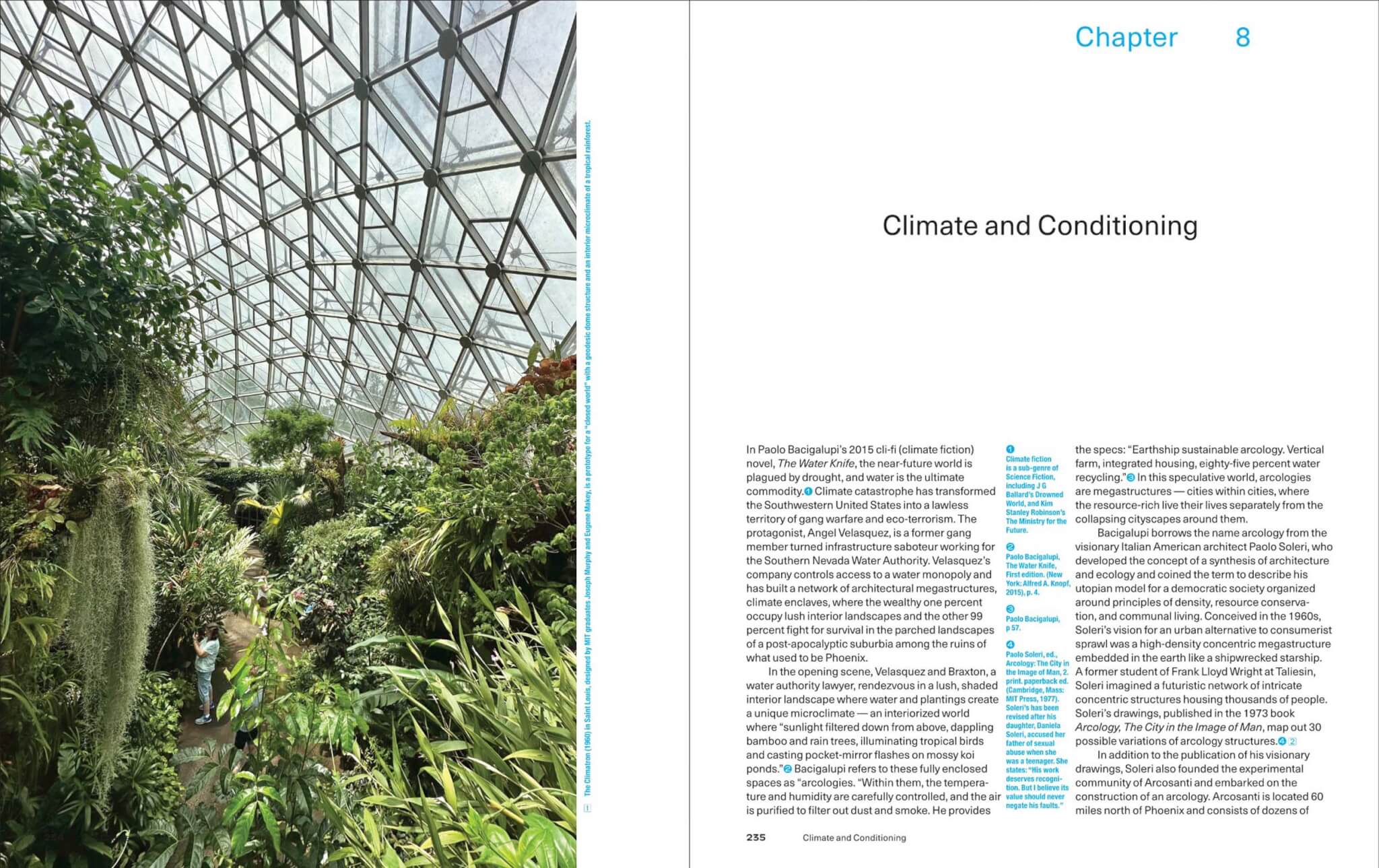

Have you seen a photo of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye under construction? I hadn’t this until I reached page 165 of Eric Höweler’s book Design for Construction: Tectonic Imagination in Contemporary Architecture. Staged on a spread opposite the abstract, white-washed version we think we know, the image reveals how banal its construction was—a concrete frame infilled by hollow clay tile blocks set in a running bond pattern.

Throughout his book, Höweler thoughtfully undermines and contextualizes a range of buildings, from historic to not-yet-built, within chapters that present major themes that shape architectural knowledge today. The result is something like a textbook or a guidebook, but it is written in a more freely associative, meandering sequence with mysterious section headers like Anticipation, Lobotomy, Risk Society, Gap in the Forest, Haunted House, and on. This is perhaps the result of the content beginning as lectures in a building technology course at Harvard GSD, where Höweler has taught for 20 years. He also co-leads Höweler + Yoon Architecture (HYA), the Boston-based firm he cofounded with his partner Meejin Yoon.

Höweler’s aim with Design for Construction is to rethink what designers can do to address “changing attitudes about performance, procurement, risk, reuse, embodied energy, and the laboring bodies that build our buildings,” as he writes. At the end of the introduction, he asks: “How much agency might design as both a field of study and a practice reasonably assume amidst global procurement, widespread calls to rid buildings of toxic materials, and international movements to improve working conditions in ways that would ensure our built environment is certifiably produced through fair labor practices? How might architects reclaim some agency by connecting processes of design, material specification, and the construction of architecture?”

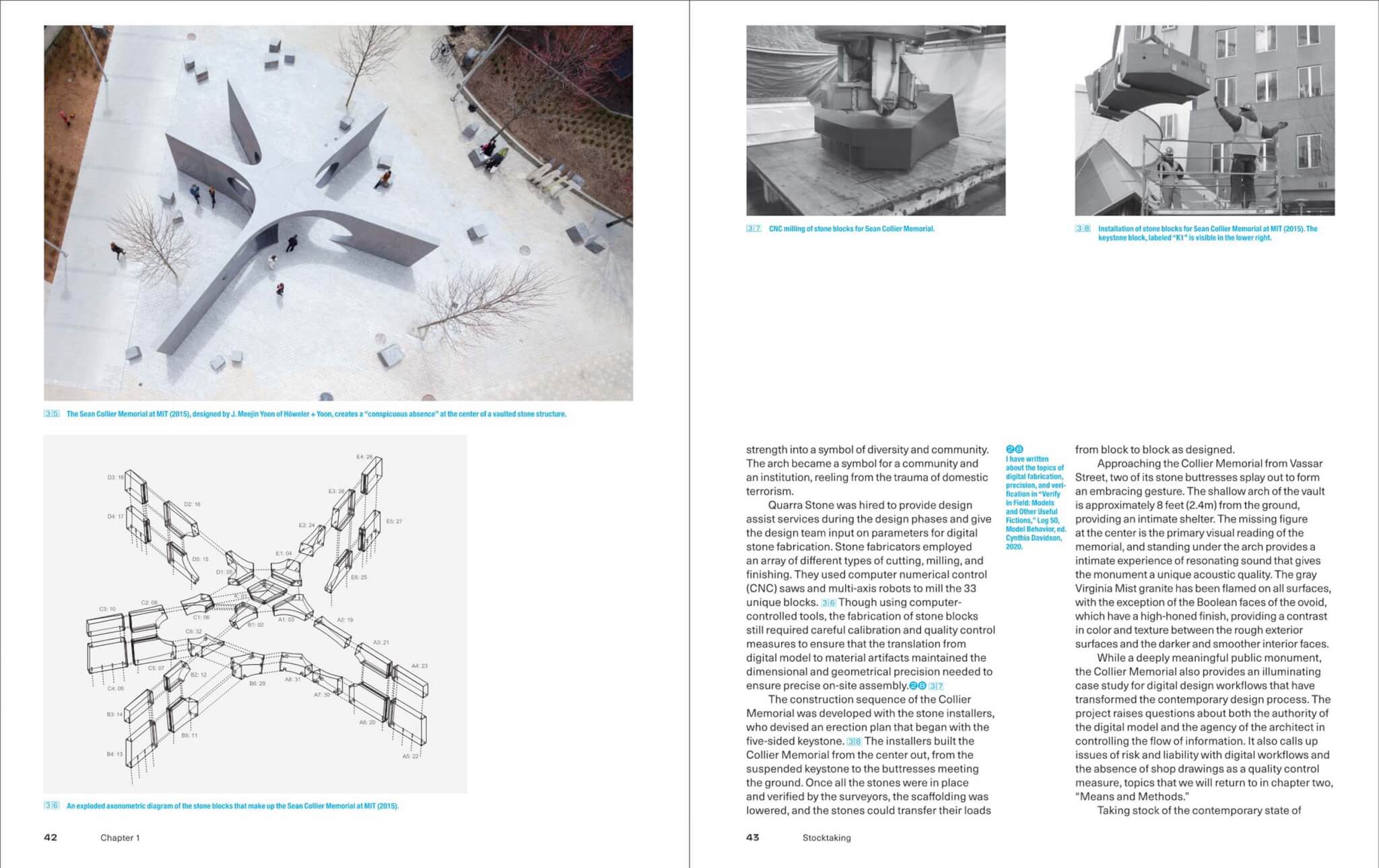

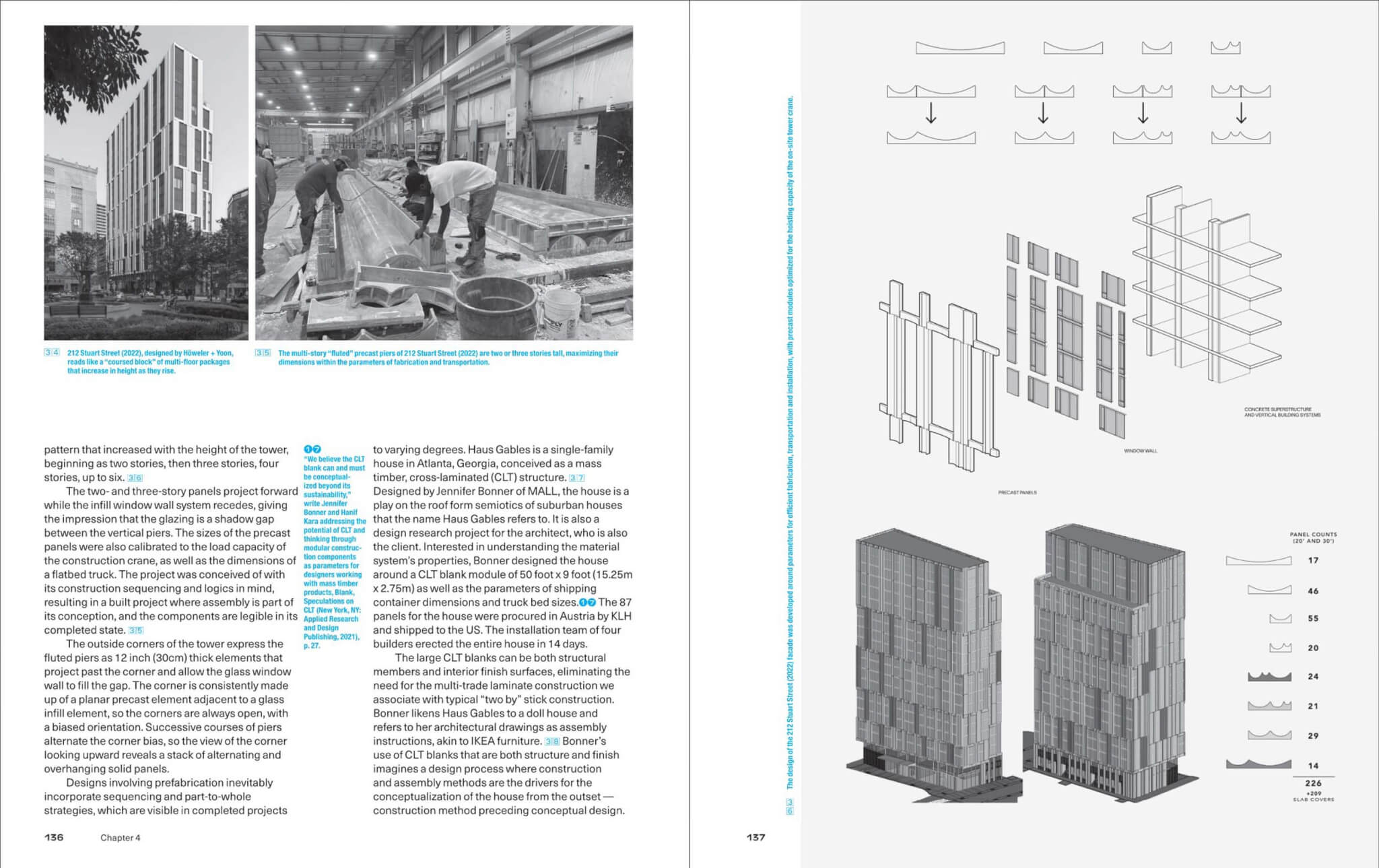

One answer comes by embracing the logic of “implementability” as the key measure of success for architecture. Throughout the book—and via text paired with a range of imagery, from “finished” photos to site and fabrication shots, drawings, diagrams, and the author’s own photos—Höweler analyzes projects to “pop the hood” of their material realities. The sensibility parallels his Instagram account, which has more than 46,000 followers, where Höweler documents his travels and fascinations.

He spoke with AN’s editor in chief Jack Murphy ahead of his January 23, 2026, book presentation at New York’s Center for Architecture.

AN: What is the origin story of this book?

Eric Höweler (EH): When I started at the GSD, I was teaching studio, but then I took on building technology classes. I taught construction systems, and recently I’ve been teaching a class called Cases in Contemporary Construction. It is thematic, and it addresses questions of tolerance and risk, materials and methods, and who are the protagonists on a construction site. Because it uses case studies, I also say it’s about looking at the world critically. It’s about criticism—being able to look at a building and see what was intended, how was it achieved, and the gap between those things. It is in the sequence of building technology classes, but I say it’s a design class, because the boundary between design and construction is really a matter of time and attention. The inertia of your design intent follows through from initial schematics into construction, and the problems you have to solve in order to implement the idea are basically just inertia.

I try to blur the line between design and construction because they are treated as two different worlds: There’s one cast of characters when we design, and then there’s another when the project is built. This gets down to the fundamental disciplinary rift between builders and designers. When I was researching this book, I went back to Mark Jarzombek’s Architecture Constructed, and he quotes Leon Battista Alberti as saying “the carpenter is but a tool in the hand of an architect.” The genesis of the discipline was a deliberate split between builders and the thinkers.

I was always looking for sources as I was teaching my class, and I found there weren’t any good ones. My students were looking at Francis Ching’s Building Construction Illustrated, but that isn’t so design oriented. There is Detail magazine or Birkhauser’s books, but those are European details and don’t capture the way we build here.

I identified a blind spot. I wrote a proposal to my publisher and said, “I can’t find a book to teach to assign in my course, so I would like to write it.” And they said, “Go ahead.” That’s a good tip: If you want to publish a book, identify a gap in the publishing landscape and make a case to fill it.

How did you translate your lectures into chapters?

EH: I started looking at books that I liked. There are a number of famous ones that translate lectures into books, like Robert Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture or John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. Sometimes two lectures became one chapter, and sometimes a lecture split into two chapters. My first proposal had 14 chapters, but these got boiled down to 10, and maybe that is too many. Tighter is always better.

I felt compelled to take the temperature of the age, so I begin with Stocktaking and then end on Construction Futures. In between, I address part-to-whole relationships, think about materials and processes, and talk about forces and form. I also write about obsolescence and the renewed interest in existing buildings, embodied energy, and adaptive reuse.

How did you finalize the case studies? Were these buildings already in your lecture slides? Or did you seek out new ones?

EH: A lot of them are in my lectures, and I talk about them all the time. Some of my students said, “I can hear your voice when I read the book because these are familiar projects you’re your lectures.” I think that’s a good thing.

There’s some of Kenneth Frampton’s tectonics and ideas of assemblage and aggregation from Nader Tehrani and Mónica Ponce de Leon; these are figures who were part of my formative years as an architect. But I am trying to be more inclusive and expansive through bringing new examples, not just from the Western canon, but looking globally at other practices that that are contributing to existing disciplinary concerns. I had a spreadsheet and a slide deck, and I would work back and forth, tracking projects.

But at the end of the day, it has to flow. Going from Theo van Doesburg’s axonometric drawings to Ensemble Studio’s Hemeroscopium House is a nice transition. One seems to be devoid of gravity, while the other seems to embody some sense of counterweights. While they appear visually similar, there are key differences that are surprising. I like this twist of visual comparisons. It’s like sorting out the difference between Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House and SANAA’s Glass Pavilion in Toledo. At first they are similar, but the more you look, the more you find nuance in the way they are assembled or conceptualized that shows you actual constructional differences.

The flow and level of expertise is well calibrated. How did you find the right tone for your audience?

EH: Great question. This book isn’t a monograph, even though it has HYA projects, and I inevitably use them when I teach. It is more of a disciplinary contribution.

I thought about voice. Is this book like a professor lecturing me about something? Or an architect? Or my friend taking me around town, pointing at things and looking at buildings? I like that last idea. It’s like my Instagram, where I take people on a tour. This voice has a nice informality. It’s not professorial, but it is curious. It says, “Let’s look under a building to figure out how it goes together.” I bring this to both my social media and my writing, and while I recognize those are different formats, the attitude is the same.

To go back to the Farnsworth House: How many columns does the Farnsworth House have? There are 12 steel ones, but if you look underneath the building, you will see the thirteenth one: It’s not structural but actually a hollow infrastructural tube where all the pipes go.

I would be happy if people came away from the book or my class looking at architecture differently—maybe more carefully or at least popping the hood. It’s useful for architects to always dig a little bit more.

Who did you have in mind as your audience for the book?

EH: Routledge thought this could be a textbook, but I don’t claim the comprehensiveness or the authority of a textbook. I think it’s for people that are interested in the implementability of architecture.

I also make a case for the architect’s agency as a figure who makes material decisions and understands sources and uses. I guess I’m aiming for a younger architect, but one who wants to make something happen. That’s why the title is Designed for Construction. It’s not “designed for design,” and it’s not “designed for theory.” The book is geared toward the purpose of implementation.

Can you tell me about the book’s graphic design?

EH: I hired Common Name, the graphic designer who did HYA’s last two books. They’re awesome. I said I wanted a book that looks like a reference book, a dictionary, or an encyclopedia. We looked at handbooks, like the Pipefitters Handbook. And then we looked at textbooks; we found those uninspiring at the end of the day.

The use of color to desaturate and highlight comes from Common Name’s conceptual approach to use color deliberately to curate the reader’s attention. It doesn’t look like a typical Routledge book, and it doesn’t feel exactly like a textbook or just a book of pretty pictures. I think it is very conceptual.

What feedback have you received about the book?

EH: Nobody has complained about my title, which I was expecting, because it says that architecture is designed for construction. It makes the point: If it’s not designed for construction, then what is it?

People have challenged the word tectonic. Nader, in particular, asked me to take a position relative to Frampton’s Studies in Tectonic Culture, which is 30 years old. I ask my students: How do you take a fantastic text and bring it into the present? I do acknowledge Frampton’s attack on the image or space of architecture by focusing on the process by which it came about—that’s his shift, from image to process, which I still like. But he was writing at a pre-internet time before we were talking about climate change, so a lot has changed, and I think his text is worth updating. Tectonics is a trigger word for some people because it locates the idea so specifically in time. But the word to me also signals things like carpentry and detailing, so for me it was an effective way to communicate that I’m interested in how things are made.

What surprised you about making this book and now seeing it released?

EH: It clarified a lot of things for me. It has also launched a lot of other inquiries; now I have ideas for future books!

Have the conversations at HYA or with your clients changed due to this book?

EH: I feel like it gives people more access to my brain. Somehow, they already know what I’m going to say—sometimes, but not always. People in the office refer to things in the book, which is helpful. But clients, not yet; maybe one day that will change.

I recommend writing a book to everyone. It will change your brain and the way you think about architecture in surprising ways.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper