Torqued beside the rail lines at Dybbølsbro Station, the Kaktus Towers cut serrated profiles against the Copenhagen sky. Designed by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), the seemingly—but not quite—twisted micro-living towers mark the edge of Vesterbro, a former industrial zone now undergoing a new wave of development.

Rising from an elevated green plateau—about 65 feet above the street, spanning a neighboring highway and IKEA—the duplicate towers induce a vicarious sort of thrill. Two gigantic biophilic figures mimic each other in a game of suggested motion. With balconies arranged in different orientations, their protruding, puzzle-like facades are both amusing and difficult to track. They seem almost to beg for reverse-engineering.

For those inclined to investigate, the process by which these forms were derived is actually quite simple. In an isometric series on the firm’s website, two generic tower volumes rise from an elevated ground plane, with floor plates uniform and repetitive. Then, curved blue arrows appear at their bases, signaling rotation. The lowest plates begin to turn, and the arrows multiply. Next, the rotation climbs the height of the towers, generating cantilevered terraces and irregular, jagged profiles. Lastly, the arrows vanish, revealing a clear snapshot of the final forms.

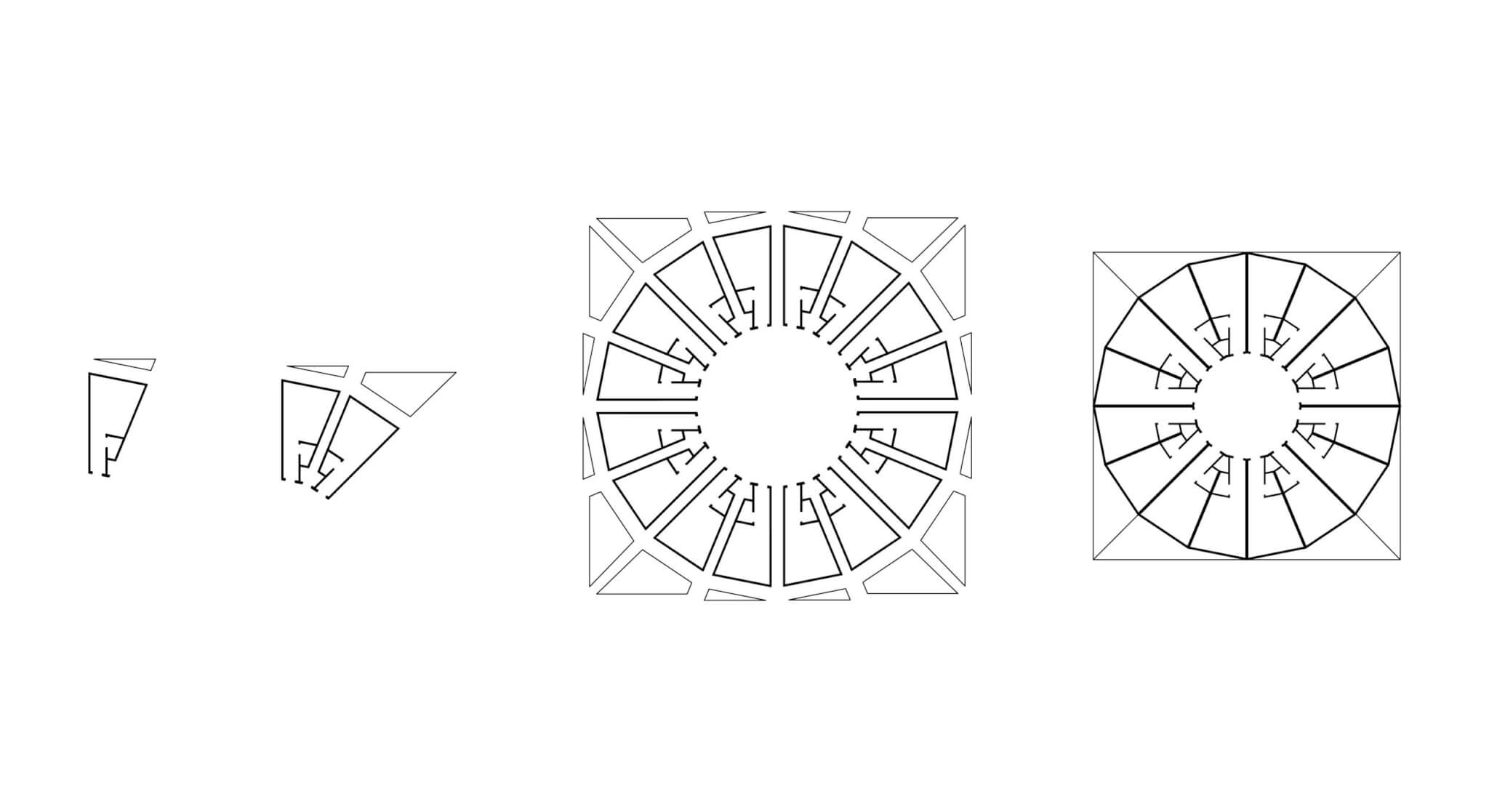

In more specific terms, the towers were conceived as a series of square floor plates, systematically rotated relative to each other. A typical floor plan shows a square perimeter that rotates 22.5 degrees per level, producing the effect of varied, cantilevered triangles along the tower’s edges.

Fixed at the center of the plan, a hexadecagon—the core tower—defines the line of enclosure. The 16-sided figure contains 16 wedge-shaped micro-units per floor, each about 376 square feet, with built-in furniture that accommodates sleeping, cooking, dining, and working.

With 16 straight perimeter modules (as opposed to the continuous curvature of a circle), the hexadecagonal form allows the facade to be rationalized as a prefabricated, unitized system. Just two balcony types—large and small—are mirrored into four variations and repeated across the entire project.

The balconies make use of a steel structure that attaches to bearing brackets within the tower core’s precast slab, limiting thermal bridging at the connection points. Along the slab perimeter, a curved ring beam ties the structure together and supports the cantilevered balconies.

The assembly was first prototyped by BIG Engineering in 2021 for a different student housing development in Esbjerg, Denmark that now includes hotel apartments. In both projects, balcony modules create an illusion of twisting when seen from most vantage points. Though, when approaching the base, the repeating pattern of cantilevers comes into focus, and the towers appear more stable.

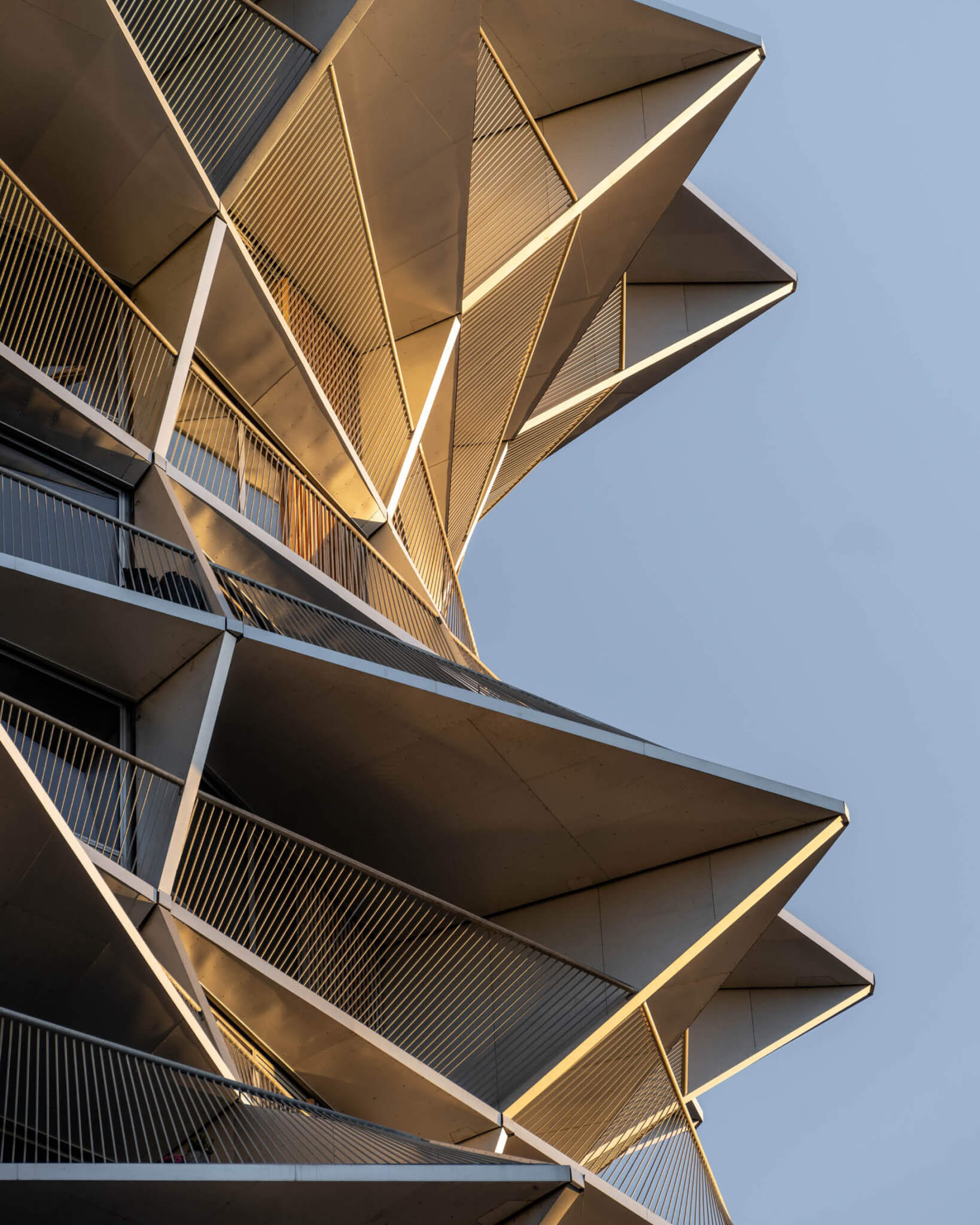

Running up each tower’s 16 edges, vertical dividers between balcony units slant to bridge the gaps between misaligned levels. These dividers give shape to the elevation profiles, adding both nuance and a sense of continuity to the system of horizontals. Spanning between these, thin aluminum railings—delicate enough not to disrupt the overall image—twist and turn to connect odd shapes.

“The facade is built on a logic of efficiency and repetition without falling into monotony,” BIG partner David Zahle told AN. “Every floor is essentially the same, but the balconies rotate with each level, creating the twisting visual effect using identical components.”

At the Copenhagen site, the balconies are sheathed in aluminum panels with a chrome-gray finish that, from a distance, almost resembles concrete. The finish makes the balcony attachments seem more integral to the structure than they actually are—a move that feels intuitive, and consistent with the logic of BIG’s diagrams.

Balancing the sharp expression of the metal, the hexadecagonal tower is clad in striated panels of vertical wooden louvers, warming the overall tone as they screen the bathroom window of each micro-unit. The wood pairs with dark, reflective glass of the doors and windows that lend the envelope a layered, recessive quality all around.

Seen from across the harbor—or better yet, in an aerial reel online—the towers look attuned to their playfully landscaped surroundings of zigzagging paths, diverse plants, and big circular voids to below. As the protruding slabs flatten in perspective, the facade begins to read like thin horizontal bands of scaffolding—flexible, as opposed to the typically more static demeanor of lasting construction. Between these lines, passing shadows fill the folds and recesses, accentuating a geometry that seems, somehow, always animate.

Project Specifications

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper