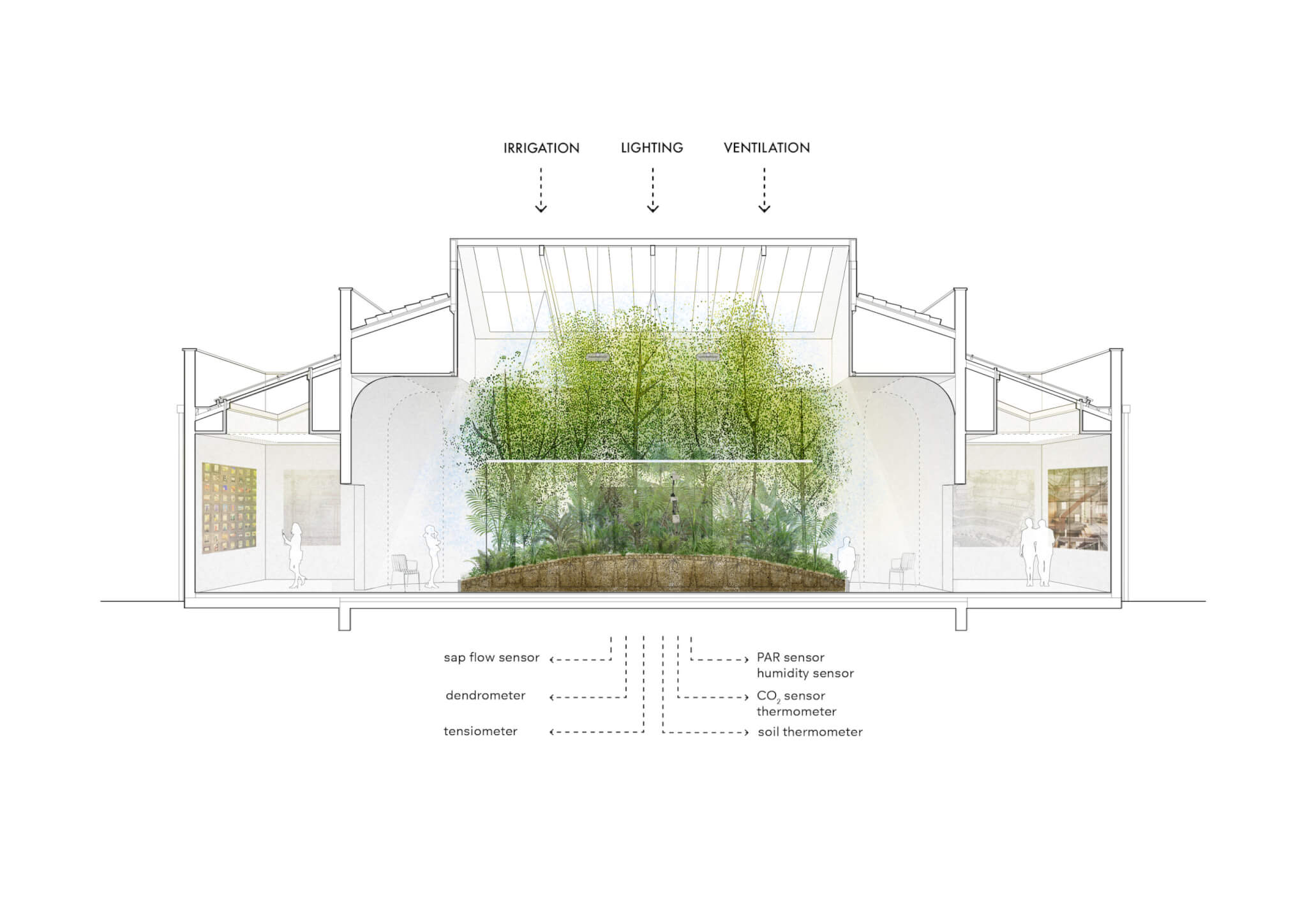

Walk through the art nouveau doorway of the Belgian Pavilion at the Giardini in Venice, and you step directly into a jungle. Building Biospheres, the installation curated by Brussels landscape architect Bas Smets and neurobiologist Stefano Mancuso, fills the central hall with a dense, rectangular cluster of four hundred tropical understory plants. Sensors throughout the display monitor plant behavior in real time—data that, in turn, drives the building’s lighting, irrigation, and ventilation.

“We see the building as a microclimate, and we see the plants as a possibility to interfere with that climate,” Smets said during the preview. “The plants are cooling the temperature in summer and heating it in winter.”

It’s not just a metaphor. The prototype demonstrates a new model for climate control in architecture, employing the “natural intelligence” that Biennale curator Carlo Ratti cites as one of the Biennale’s themes. Instead of ornaments, the plants here are agents in a calibrated feedback loop. The installation is a working system, developed with Ghent University ecophysiologist Kathy Steppe and engineer Dirk De Pauw.

The key premise is comfort: If the plants are comfortable, people are comfortable. Tropical species were chosen for their environmental preferences, which align closely with human thermal comfort. However, this prototype system is not perfect: Smets notes that humidity is still a challenge using only natural ventilation. A series of adjunct proposals from emerging Belgian practices—like a hemp-lime wall system or bamboo-based humidifier walls—expand on the idea, exploring how to stabilize interior moisture levels through architectural materiality.

More provocatively, the team imagines how to deploy these ideas in existing buildings. For a 1967 residential tower in the Pacific housing complex, a scheme would convert several floors into “climate rooms,” lush green environments fed by water pumped from a belowground aquifer. These plant-filled spaces would act as living lungs for the building, distributing cool, clean air throughout the apartments.

Another pilot project targets the former office building of glass manufacturer Glaverbel, a ring-shaped 1960s structure whose empty courtyard would be enclosed to create an interior biome. Plants like king ferns and giant taro—species from Southeast Asia’s humid forests—will anchor the system.

“Architecture has always been about survival,” reflected Smets, whose public projects, including a new square at Notre-Dame Cathedral of Paris, increasingly engage with the impacts of climate change. “It’s about protecting us from wind, rain, and snow. But over time, architecture began to produce its own artificial climate—sealed off from the biosphere that allows life.” Building Biospheres argues for reversing that separation, engaging with the natural world in an intimate form of collaboration.

Alex Bozikovic is the architecture critic of The Globe and Mail and the author of books including 305 Lost Buildings of Canada.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper