Architecture and Videogames: Intersecting Worlds is a new book edited by Vincent Hui, Ryan Scavnicky, and Tatiana Estrina and published by Routledge. The book features contributions from architects and educators including Viola Ago, Galo Canizares, Graham Harman, Damjan Jovanovic, Kristen Mimms Scavnicky, Jose Sanchez, and Leah Wulfman, and its title unites architecture’s reliance on digital technology with the discipline of game design. The book “begins a study of virtual space produced and nurtured by videogames through an architectural lens,” its editors write in a preface. Individual subjects are pulled from both academic research and architectural practice. In the text below, excerpted from a chapter in the book, AN contributor Ryan Scavnicky connects virtual architecture to paper architecture and articulates why shared digital spaces are relevant for architects today.

The space of a videogame is the space of architectural thinking. After all, so many buildings are first conceptualized and designed as a 3D digital model, so it makes sense that examining videogames as architectural works requires only minor shifts in the application of core architectural ideas. This creates a new extended boundary of architecture and the public imagination and offers a glimpse into a future of spatial design where virtual and physical spaces merge, opening doors to new domesticities and other potential worlds at the intersection of these two dynamic fields.

Understanding the role that architecture plays within game environments must include consideration of societal desires of play in order to understand the potential spatial and cultural effects of that game. In any particular narrative, the buildings inside of an environment can be understood as characters just like any other. This character is sometimes helpful, like Howl’s Moving Castle, mysterious like the Inverted Castle in Castlevania, or straightforwardly evil like Bowser’s Castle. As an example, my studio Learning from Los Santos looked at the Gerudo Ice House from Zelda Breath of the Wild and diagrammed it through Jay Appleton’s prospect and refuge theory, as well as points of spatial conflict between player and monster or NPC. We then reimagined the building from virtual space to “real” space as a gas station, which revealed extreme similarities between game and real architecture, and the space of player vs. monster with player vs. worker.

As videogames become more immersive and culturally mainstream, they begin to shift from mere 3D environments to entire ecosystems. Meaning the space of a game is not limited to the virtual model in which the players interact and the buildings they interact with, but the physical and social containers surrounding the leisure time and space of play. These containers are as diverse as a living room couch in a single apartment for a gamer playing with friends spread across the world, a busy traveler playing a solo handheld game while half listening for the call to board their next flight, and a chat room with thousands of viewers on a Twitch stream. Each of these scenarios are spatial containers that provide two layers of oscillating information. The creation of virtual architecture rests upon understanding these mixed mechanics layered with social interactions that are structured, staged, and organized into an intentional spatial experience.

Any simulated world exists in relation to the known world. In architecture, models of possible worlds are used as a way to make a statement about the world today and how it should change. Historically referred to as “paper architecture,” buildings can be more influential as unbuilt plans than they are asa finished product, hence the design stays “on paper.” Canonical figures like Daniel Burnham and Frank Lloyd Wright often pointed out the crucial way architecture can simulate a new reality for people and convince them that it was indeed possible. Still today there is a strong interest to pursue this kind of thinking in architecture, what Aaron Betsky calls “anarchitecture” in his latest tome The Monster Leviathan (2024). Ultimately, to be effective, paper architecture must stir the public imagination in such a way as to spark real change.

Paper Visions

“Only through the structure of the image, and in no other way, can the reign of necessity merge with the reign of freedom.”—Manfredo Tafuri, Toward a Critique of Architectural Ideology (1969)

Visionary architecture is an intentional type of paper architecture that concedes its impossibility in order to interrogate various conditions of the world. Perhaps none have worked so closely with this as a type than Lebbeus Woods. He famously kept a blog where he playfully and directly interacted with virtual commenters.6 In a post titled simply “Visionary Architecture” from December 11, 2008, Woods identified three essential attributes. First: the projects propose new principles by which to design for the urban conditions they address. Second, the designs are total in scope. Third, the designs invent new types of buildings (2008). Woods gives two examples: Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin and Steven Holl’s Spatial Retaining Bars. Examining these canonical examples alongside outsider architectures through this lens will allow us to speculate a new set of Woods’ conditions to satisfy.

In 1925, Paris was suffering from overcrowding and poor housing conditions while steel construction was allowing most major cities to build vertically. In response, Le Corbusier designed a series of buildings that would house one million people right in the city center. He proposed demolishing a large section of buildings extending along the Rive Droite directly at Île-de-laCité, enough room to clear space for an airport runway. The proposal was ultimately rejected, but the ideas it instigated changed the profession forever. Some have turned out to be good ideas, like housing many people in spacious and equitable living conditions, like Co-Op City by architect Herman Jessor, which recently turned 50 years old. Some have turned out rotten, like the clearing of large quantities of a historic core. One particularly devastating example is the west end of the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood in Cincinnati that was cleared to create the Interstate 75 freeway, displacing a majority black population.

In 1989, the city of Phoenix, Arizona searched for answers in planning the growing metropolis and its seemingly endless encroachment into the desert. Single-family home zoning was putting incredible stress on the highway system, causing the city to spread out of control. Steven Holl proposed Spatial Retaining Bars, a giant development of horizontal towers to form an implied edge between the city and desert. This idea was not only to mark the edge, but to contain the developments and potentially organize the chaos. What would’ve been a massive undertaking at the time, we may consider today to have been well worth the effort. The city has now spread for hours in every direction, causing extreme reliance on automobile infrastructure that stresses the city to the limit. While these two examples from Woods exist squarely within the discipline of architecture, we next consider an outsider example, while staying in the architecture field.

In late 2021, Dennis McFadden of the architecture review board of UC Santa Barbara tendered a resignation letter just as a new building proposal for the school was made public. The proposal, designed by then 99-year-old billionaire Charlie Munger of Berkshire Hathaway, made headlines because a majority of the building’s 4,536 beds were without a window to the outside. This controversial decision was described as one made out of necessity: UCSB is in desperate need of housing. Yet, this housing need could be filled like many other universities around the world whose dorms have windows, so the windowless rooms understandably drew a lot of public scrutiny. The media outcry earned the project the nickname “Dormzilla” prompting the university to back off, demonstrating the societal values that effective paper architecture can tease out. The vision, it seems, was out of sync with the limits of the living conditions expected by the masses, and therefore pressured society to organize around its defeat. Lastly, we look for an example entirely outside of the field of architecture that created a massive change to civic space.

In the summer of 2016, Americans couldn’t get enough of the mixed reality mobile game Pokemon Go, which revitalized the brand in the hearts of millions who grew up with the franchise but found themselves decades removed from their old GameBoy. The game works by building a digital twin of your mobile device map, and by walking around you encounter Pokemon, which you try to capture using mixed reality passthrough via your camera. Success in the game involves hatching and leveling up your Pokemon by actively walking around with them, which uses the phone’s step tracker. So, one must do a lot of traipsing about and exploring your neighborhood, looking for landmarks called “PokeStops” for you to get items, trade, and replenish.

These PokeStops became overnight sensations, attracting throngs of people to municipal buildings, libraries, and parks in large numbers. The number of Pokemon Go players newly introduced to public life stimulated civic spaces in a way that was so extraordinary that in July of 2016, Pokemon Go players stumbled upon two dead bodies a week while venturing into off-thebeaten-path locations. The game is highly interactive between players who are physically proximate, with items like a “lure” which would attract rarer and more frequent Pokemon to all players in the vicinity. It takes hours of work to earn just a single 20-minute lure, or one can buy them for a fee. But in one important instance, my local dive bar in downtown Los Angeles was advertising the placing of a “lure” on the three different PokeStops within range of their patio during a happy hour complete with drink specials. Meanwhile, empty bars without PokeStops were desperately trying to figure out how to add them.

Pokemon Go is a spectacular example of gaming’s ability to transform the built environment at a large scale by creating a mirror virtual architectural world. This leads into a future of visionary architecture existing in the deep societies, new economies, and interactive mechanics of future games. Just as we can’t imagine a videogame made by only a single person, we can no longer theorize architecture by a single author. Both architecture and videogames should be theorized as coming from multitudes of authors across experiences, backgrounds, and specialties. Thus, we can speculate an update to the three points suggested by Woods for a new form of virtual visionary architecture. First: the projects propose new principles by which people interact and behave. Second, the designs are total in scope. Third, the designs invent new types of spaces.

Ethical Considerations

An additional challenge when judging videogames as architecture is the almost universal requirement to commit an act of violence or murder in order to experience the space in itself. In the essay On Style, Susan Sontag addresses the concealment of moral faculties to properly judge the aesthetic content of a work of art. She presents the example of writer Jean Genet, and most of the characters in King Lear. Sontag writes “it is immaterial that Genet’s characters might repel us in real life. The interest … lies in the manner whereby his ‘subject’ is annihilated by the serenity and intelligence of his imagination.” Yet Bernard Tschumi’s famous Advertisements for Architecture state that “to really appreciate architecture, you may even need to commit a murder.” The conceit here is that it is the actions performed, not architecture, which defines space. If you want to make meaningful space, you could do something memorable in it, the most transgressive example being murder. If space is defined by its actions rather than its walls, the actions of pretend play, community-building, and leisure created and nurtured in virtual environments are as transgressive as Tschumi could ask for.

It is certainly possible to have virtual mediums without narratives of murder, so to have a pure aesthetic experience of a certain game, what other faculties might we be able to suspend? Within this framework, we see an agency of architectural thinking develop. The virtual architecture space of a game like Journey, which puts two random players together on a quest but limits their ability to communicate, examines our standards of behavior and teamwork via storytelling. Games like Zelda: Breath of the Wild create an architecture that showcases visions of ecologies which stand as a model for reparative natures. Even games like Fall Guys create a virtual architectural space that tests our understanding of bodily advantage, as each player has the exact same physical ability.

In suspending those faculties, it is possible to introduce a player to a world as a critique of their own, in essence, completing the notion of a virtual visionary architecture. As Lebbeus Woods said of his own work “I’m not interested in living in a fantasy world. All my work is still meant to evoke real architectural spaces. But what interests me is what the world would be like if we were free of conventional limits. Maybe I can show what could happen if we lived by a different set of rules” (2008).

Pixels and Poetry

[Academic architecture] is “a dismal science, which in every instance demands of our ideas that they finalize themselves as solutions … close themselves in, prove themselves, eradicating the mystical, the unspeakable, eradicating every last trace of poetic ambiguity …”—John May, Under Present Conditions Our Dullness Will Intensify

To make space for these kinds of activities, virtual space must be imbued with meaningful cultural value. Game designers already know how to make a space meaningful to players. The tactics and strategies employed (the passing of time, player and community participation, etc.) mirror historical architecture theories attempting to create the same type of effect. When a player has agency to play a game in a way that is enjoyable for them, the play creates meaning because the game space itself has an embedded history. The game holds within it the marks and changes made by the player. And even greater is the meaning created by participatory and community cultures inside of games. The sandbox style game, for example, is the ultimate game type to foster meaning and engagement with an environment.

In the Seven Lamps of Architecture, John Ruskin theorized architecture and its relationship to craft (1849). Lamp Five, the lamp of life, argues that buildings should be evidently made by human hands so that the joy and history of the craftsperson or laborer is seen and enjoyed. At first glance, this seems easily related to the environment of a game changing as the player interacts with it. However, there is an important difference to bear in mind with the lamp of life in relation to labor. The craftsperson referred to by Ruskin is a builder, not the homeowner. We can better relate this theory with the signature worldbuilding details and easter eggs of contemporary production. In an era so marred by reports of the poor working conditions of videogame studios, these touches bring a player in important close relation to a new type of craft. Thus, we could speculate a future architecture wherein the labor of the multiple workers or craftspeople is given agency enough to leave a signature on the world built for a player to inhabit.

When it comes to domestic space in particular, Ruskin believed that “restoration, so called, is the worst manner of Destruction” (1849). Meaning that the history of a building and its age is preservation itself. The markings and scars of inhabitation are the very soul of the work of architecture. To see one’s own effect on the environment is to truly live inside of it. In the same way that games mark the passage of time and progress of the player by changing the environment, so does a house grow with a family. What’s important here is that there is little difference between the marks you’ve made on the wall of your childhood home and the weapons you’ve hung to display in the house you can purchase in Zelda Breath of the Wild—both are a particular shared cultural experience made through meaningful insertions on space.

Game mechanics like the total loss of an item when it wears out or the glass shattering permanently on the car I shoot up in Grand Theft Auto properly reflect this desirable architectural agency. Other successful examples include when franchises like Halo remastered the infamous Blood Gulch multiplayer map, or the smashing success that Fortnite had when re-releasing its original maps. These sentiments are felt through contemporary meme culture, which often has pictures of places like the Warehouse in Woodland Hills from Tony Hawk Pro Skater with words like “Scientists at Harvard University have created this 3D Model depicting what The Garden of Eden may have looked like” or “Images you can hear” or my personal favorite “You’ve just ordered Pizza Hut and a 2L Mountain Dew. You’ve loaded up Diablo on your PC. No school tomorrow. Your parents don’t care if you stay up all night long. A perfect Summer night. You are 39 years old. The year is 2023.” These memes showcase a contemporary longing which equates a particular virtual space with the comfort of domestic leisure.

According to the website Fortnite.gg the game typically has around 400,000 active players at any given time, but during the release of classic original maps on Thursday, November 2, 2023, it peaked around 3.1 million active players. Imagine Cleveland, Ohio swelling from 390,000 people to hosting Rod Stewart’s free 1994 show at Copacabana Beach in Rio de Janeiro, which had an audience of approximately 3.5 million. This type of swelling is among the largest gatherings of people in human history, and will only grow in scale and proportion next to the obvious limitations of the purely physical world. As a study of this phenomena, I wondered how the spaces and floor plan of Control, a videogame supposedly taking place in 33 Thomas Street (formerly the AT&T Long Lines Building) would look if we tried to fit it into the hulking Manhattan mass, and what it would be like to visualize all the active players of the game moving through it, from their own space.

It’s Architecture With Or Without Architects

The discipline of architecture has always grappled with the extraordinary expanse of buildings and spaces in the world and the difficulty surrounding the choice of which few to denote as canonical examples. In 1964, Bernard Rudofsky organized an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City called Architecture without Architects in which the canon of architecture history itself was challenged (1964). Presenting what is now broadly known as vernacular architecture, Rudofsky interrogates the notion of the master builder and its history by presenting works built not by individuals but by cultures responding to specific local material conditions and environments. In the book written for the exhibition, Rudolfsky writes “part of our troubles results from the tendency to ascribe to architects—or, for that matter, to all specialists— exceptional insight into problems of living when, in truth, most of them are concerned with problems of business and prestige.”

Photographs of the MOMA exhibition, however, reveal images of indigenous and vernacular structures without context positioned across a simple stud wall system. The show was designed for people to take inspiration from this architecture and make new buildings from it, which perpetuates the cycles of prestige Rudofsky so despises. It additionally created a clear border between the “insiders” and “outsiders” of the discipline by presenting this work to a particular audience of museumgoers, which resulted in the fetishization of the work itself rather than learning with interest, empathy, and respect. Rudofsky again, “the present exhibition is a.. vehicle of the idea that the philosophy and know-how of the anonymous builders presents the largest untapped source of architectural inspiration for industrial man” (1964). This smells more like colonialism than honest representation.

In opposition to this, a YouTube video by Andres Souto of mUcHo estudio/taller called El Grand Tour gives a guided tour of the fantastic and wild speculative architecture available on the Sketchup Warehouse. This type of representation opposes the fetishizing quality because it speculates a radical repositioning of authorship. Instead of a survey of amateurs by masters prepared to pounce on the discovered unnamed talent, the video supposed the amateurs have the mark of true genius and it is us who should marvel at the work. This comparison and reversal showcases a new possibility for architecture to work through challenges of authorship and vernacular as it navigates changes in world culture and then remixes it. A better framework for this type of creation is Jill Stoner’s Toward a Minor Architecture, which highlights the need to take things apart in our constructed wasteland and emerge from power structures to liberate from below (2012).

Yet we still must rely on the idea of vernacular architecture not for fetishization of form over materials, mechanics, and shared authorship but the way vernacular creates and nurtures a shared domestic image. A recent commercial for Nintendo Switch showed two brothers playing Goldeneye 007—a game released on the Nintendo 64 in 1997—online with one another in February of 2023. While playing together in their current lives, they are transported to their childhood bedroom where they have stored memories of domestic leisure and play. This meaningful physical-digital interaction, and the clear reflection on virtual space as an extension of the domestic, has resounding implications for the future of all spatial design.

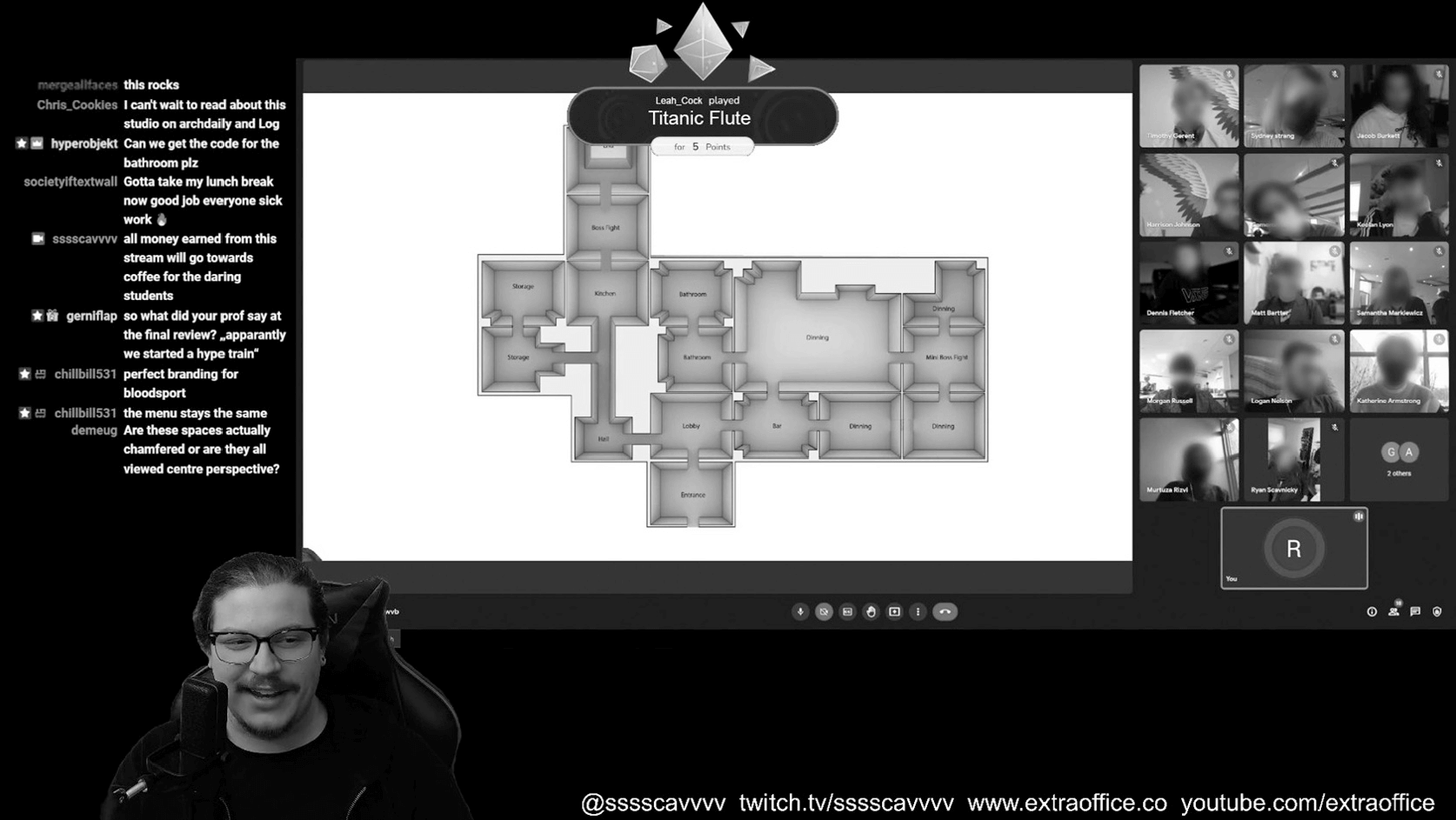

This manifests through my work and research as a gamer and an architecture teacher. Building on sentiments expressed poetically by a famous post from Viviane Schwarz on X (formerly Twitter) which stated “Zoom sucks, we started having editorial meetings in Red Dead Redemption instead. It’s nice to sit at the campfire and discuss projects, with the wolves howling out in the night.” So during 2020, to experience immersive space as a class, I held desk crits remotely, but rather than Zoom, we met inside of a virtual space called Sansar, which comes with a variety of community-built avatar skins. We also held our final critiques online and instead of a typical jury, we invited a Twitch chat to do a “chat plays” stream where the chat is the jury. This generated feedback not just by architecture faculty but by outside characters, truly opening the architecture jury to the broader public while experiencing a new type of shared domestic space.

Through slightly shifting core ideas and foundational concepts, domesticity in architecture is changing from one that is contained to one that leaks into shared virtual containers. The merging of videogames and architecture reveals a dense stew of spatial design, societal influence, and cultural significance. Videogames, evolving into immersive ecosystems, transcend digital environments to become cultural artifacts akin to physical buildings. They shape behavior, reflect societal norms, and transform physical spaces, destroying the assumed boundary between virtual and real-world architecture.

The concept of virtual visionary architecture has emerged, and it promises collaborative design and participatory experiences that reflect the multiplicity of voices in our society. Whether huddled around a living room console or engaging with a global community through online platforms, players inhabit diverse spatial contexts that enrich their experiences. Understanding the intricacies of these mixed domestic mechanics and social interactions is essential for reimagining the discipline of architecture through the design of virtual worlds as a new project of our shared cultural imagination.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper