Architecture Follows Fish: An Amphibious History of the North Atlantic

André Tavares

The MIT Press

$50

On Columbus Day in the sixth grade, I told my teacher that the Genoan was not the first European to reach the New World. Portuguese fisherman, I noted, had dried their cod on the shores of Newfoundland for centuries, for which impertinence I was chastised. Miss McDonnell’s ignorance could have been erased had there only been André Tavares’s comprehensive amphibious history of the North Atlantic, Architecture Follows Fish.

The Porto-based architect asks us to imagine a fish’s-eye view of architecture. He writes: “An amphibious gaze transcends histories of architecture as an exclusively human activity or art form.” Tavares sees it “as a component with a larger socioecological history.” Fish know no nationality, and while much of the framework of history is political, this book places humankind at the pivot between a consumer product and a natural resource. “Biology, technology, processing, politics, and consumption are lenses to help us perceive just how intimately entangled fishing and terrestrial landscape are.”

Casting his gaze from the Industrial Revolution to the era of frozen fillets and globalization, Tavares addresses docks, storage sheds, and processing plants—what Bernard Rudofsky referred to as “non-pedigreed architecture.” Modernism and Le Corbusier, nevertheless, are mentioned—the book opens with a 1950 severe white cube of a freezing plant in Myre, Norway. There was a Cold Storage Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, and three years earlier Adler & Sullivan tried to “develop a language for a novel public monument” with its Cold Storage Exchange. The 1934 Massarelos fish market in Porto, designed by Januário Godinho, undoubtedly new to most readers, became an emblem for the city and is “a point of reference in modern architecture” in the history of cod-obsessed Portugal.

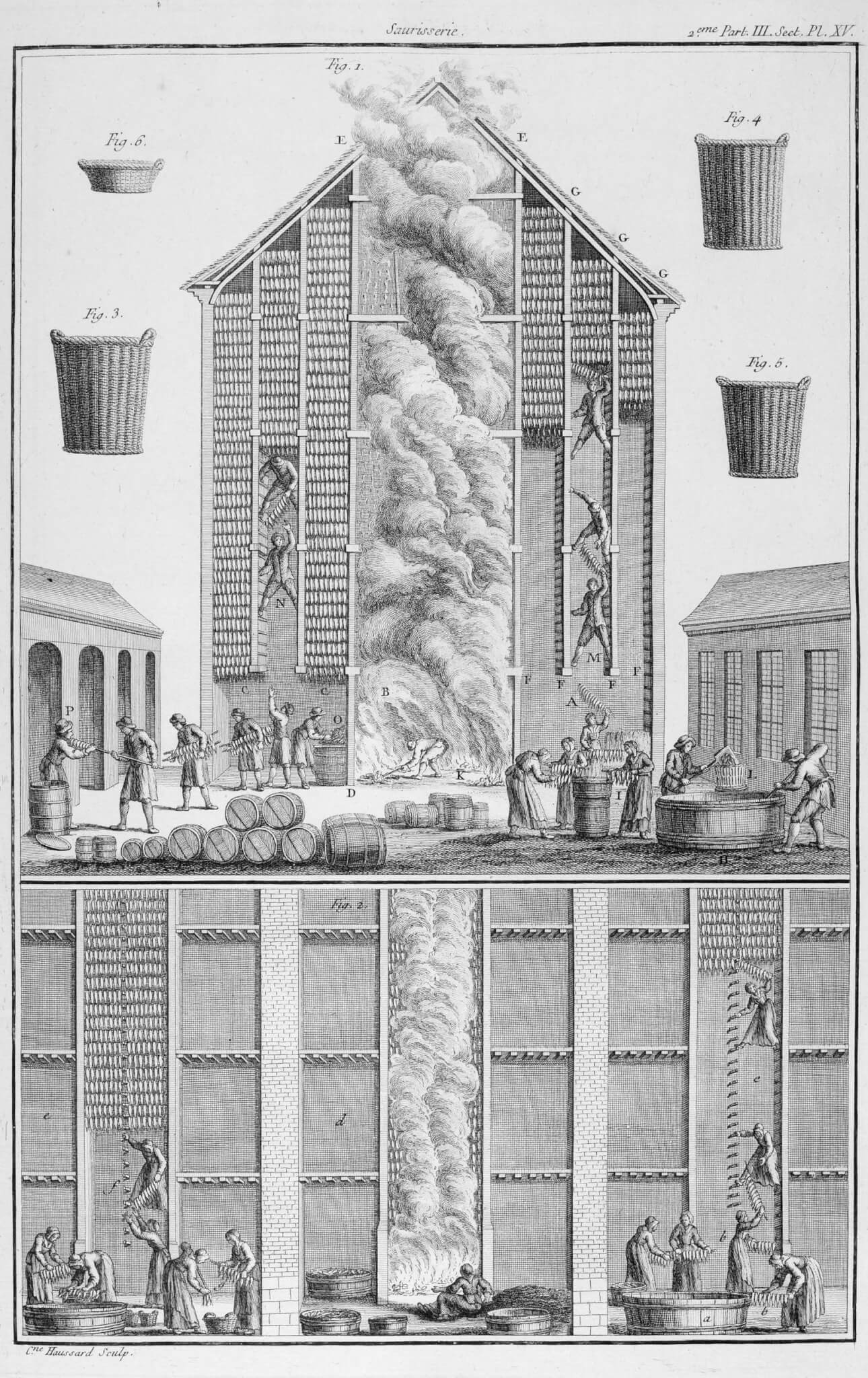

Piscatorial architecture is a reflection of transformations in technology. Revealing how fish shape landscape and architecture, Tavares is not so much interested in the form of buildings as in a “desire to understand built manifestations of the human presence within nature.” The intersection of various technologies marks the architecture of fishing, so there is a lot of information here on oceanography and marine biology. Cod and sardine fisheries are different, for example, one depending upon drying, the other on canning. Hence, their respective architecture of drying racks, warehouses, cold storage, boats, nets, and traps is different. Conversely, since this is an ecological history, marine ecosystems are affected by what we build on land.

Eating fish is just one aspect of a larger food chain, wherein fish is a commodity—also a nonrenewable one, the success of which depends upon its exploitation. Fishing is less like agriculture than mining, in that once the vulnerable fish are extracted from the ocean, none are left. The fishing villages clinging to the rocky shores of Newfoundland serve as an example of how the fundamental supporting structures on land were altered as the cod moved farther from shore; the introduction of factory ships in the 1950s rendered many villages redundant. In the 1850s, sardine fishing, which doesn’t need harbors, was transformed by the introduction of canning.

The evolution of such technological and political changes can be charted by following whaling. The discovery of oil in western Pennsylvania in the mid-19th century came at the apogee of whaling, and prior to that we can read the landscape and structures formed by the hunting of the Leviathan. The first Nantucket whalers fished close to shore, but as they chased the sperm whale around the globe, bigger boats, longer journeys, and more infrastructure changed the island and spelled its doom as an industrial powerhouse.

The growth of the food-processing industry, spurred by the ability to can sardines, saw the construction of huge market halls, like that in Lorient, Brittany—a Les Halles for fish, accompanied by the dredging of a new harbor. The Italianate palace for Billinsgate Market on the Thames in London was designed for the social aspirations of the Fishmongers Company rather than proximity to the fish. Billingsgate, Hungerford, and Covent Garden were all connected to the railroad, allowing fish to become available to the urban poor. Fish and chips is still Britain’s most popular takeaway food.

“From the perspective of fish, architecture is a passage. Appearing on its path from animal to commodity, buildings are interfaces, facilitators inscribed within a sequence of logistical movements leading from the harvesting to their arrival in distant places to be turned into food.” In this process, Tavares writes, “no building typology has had a larger impact than freezers.” Refrigeration made possible new products like fish sticks, as witnessed by Clarence Birdseye’s 1924 patented “Method of Preserving Piscatorial Products.” Iceboxes, along with improved schooner designs, drove fish consumption way up. One of the main reasons the Nazis occupied Norway was for its rich fishing grounds; their factories increased production of needed protein for the Reich to 35 times prewar levels. Under Portugal’s Salazar dictatorship cod fishermen were mythologized as Atlantic heroes “following a glorious nation’s destiny.” Lisbon’s cold-storage facility became a symbol of national self-sufficiency during World War II.

The North Atlantic has been overfished, technology has been unable to offset the inevitable decline, and there is “no marine counterpart to the picturesque quality of terrestrial ruins.” As Rachel Carson wrote in The Sea Around Us, “We still haven’t become mature to think of ourselves as only a very tiny part of a vast and incredible universe.” Such interconnectivity, however, is Tavares’s grand theme. Architecture Follows Fish is not an easy meal, for there is a lot to digest here. But it is a bold, significant, and even revolutionary approach to architectural history.

William Morgan writes extensively about New England architecture. His latest book is The Cape Cod Cottage (Abbeville Press).

This post contains affiliate links. AN may have a commission if you make a purchase through these links.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper