In 2025, architecture moved through prestige cinema and television, danced inside fashion ads and music videos, shrank itself into pocket-sized books, and fully surrendered to the algorithm. If the discipline once relied on monographs, journals, and public-facing institutions to mediate its public life, this year suggested those channels no longer feel sufficient. Architecture was no longer being explained so much as performed, aestheticized, memed, contested, and occasionally misread, often by people far outside the profession.

What united these moments wasn’t coherence but pressure. On screen, architecture oscillated between myth and menace; in print, publishers questioned whether books still made sense; online, the discipline bypassed gatekeepers altogether. Even criticism, long tethered to legacy platforms, showed signs of reconfiguration, as one of the field’s most consequential recognitions landed not with an institutional masthead but with a freelance voice working in digital media. At the same time, some of the platforms that once reliably carried architectural history and civic storytelling began to feel newly precarious, their futures suddenly uncertain.

More than a year of media appearances, 2025 revealed just how fragile the cultural infrastructure supporting architectural discourse has become.

Architecture took the screen in 2025 and refused to behave

Architecture had an unusually charged year on screen in 2025, beginning with the cultural eruption around The Brutalist. Brady Corbet’s awards-season juggernaut turned concrete into cinematic spectacle, reintroducing Brutalism to mass audiences while simultaneously alienating much of the architectural world. The film sparked backlash over its mythologizing of the architect as a lone genius, its muddled historical references, and controversies around AI-assisted production. The Brutalist exposed how easily the discipline can be flattened into aesthetic shorthand, provoking debate about Brutalism and who gets to narrate architectural history in popular culture.

Television proved far more incisive. Severance returned with a second season that treated architecture not as symbolism but as a system of control. Its immaculate midcentury interiors, shot in and inspired by Eero Saarinen’s Bell Labs, turned modernist order into existential dread, with endless corridors, rigid grids, and blank surfaces doing the narrative heavy lifting. At Lumon’s headquarters, architecture functioned as management strategy and psychological weapon, staging a slow-burn horror of workplace alienation that felt uncomfortably familiar. Unlike The Brutalist, Severance understood that architecture’s power isn’t in monumentality, but in how it disciplines bodies and behavior.

Then there was The Studio, Seth Rogen’s self-aware Hollywood satire, which leaned into Frank Lloyd Wright and John Lautner as architectural shorthand for cultural legitimacy. The television series’ modernist settings were knowingly performative, status symbols masquerading as artistic seriousness, mirroring an industry obsessed with appearing timeless while endlessly recycling itself.

The contrast between the Oscar-winner and the television shows was hard to miss. When architecture was framed as heroic myth, it buckled under scrutiny; but when treated as infrastructure, ideology, or performance, it became far more incisive. In 2025, the most compelling screen architecture wasn’t reverent or monumental, it was unsettling, self-aware, and deeply suspicious of authority.

That suspicion may soon find its clearest subject yet. Matthew Rhys is reportedly in talks with Netflix to dramatize The Power Broker, shifting the focus away from architect-as-auteur fantasy toward infrastructure, bureaucracy, and metropolitan power at scale.

Small books published big feelings

If architecture publishing seemed to share a resolution in 2025, it was to rethink the container. Not the ideas themselves, but the formats used to carry them. Across books, magazines, and even a very L.A. newsprint experiment, the year signaled a shift away from unwieldy tomes and inherited publishing habits, and toward formats better suited to how architectural discourse actually circulates today.

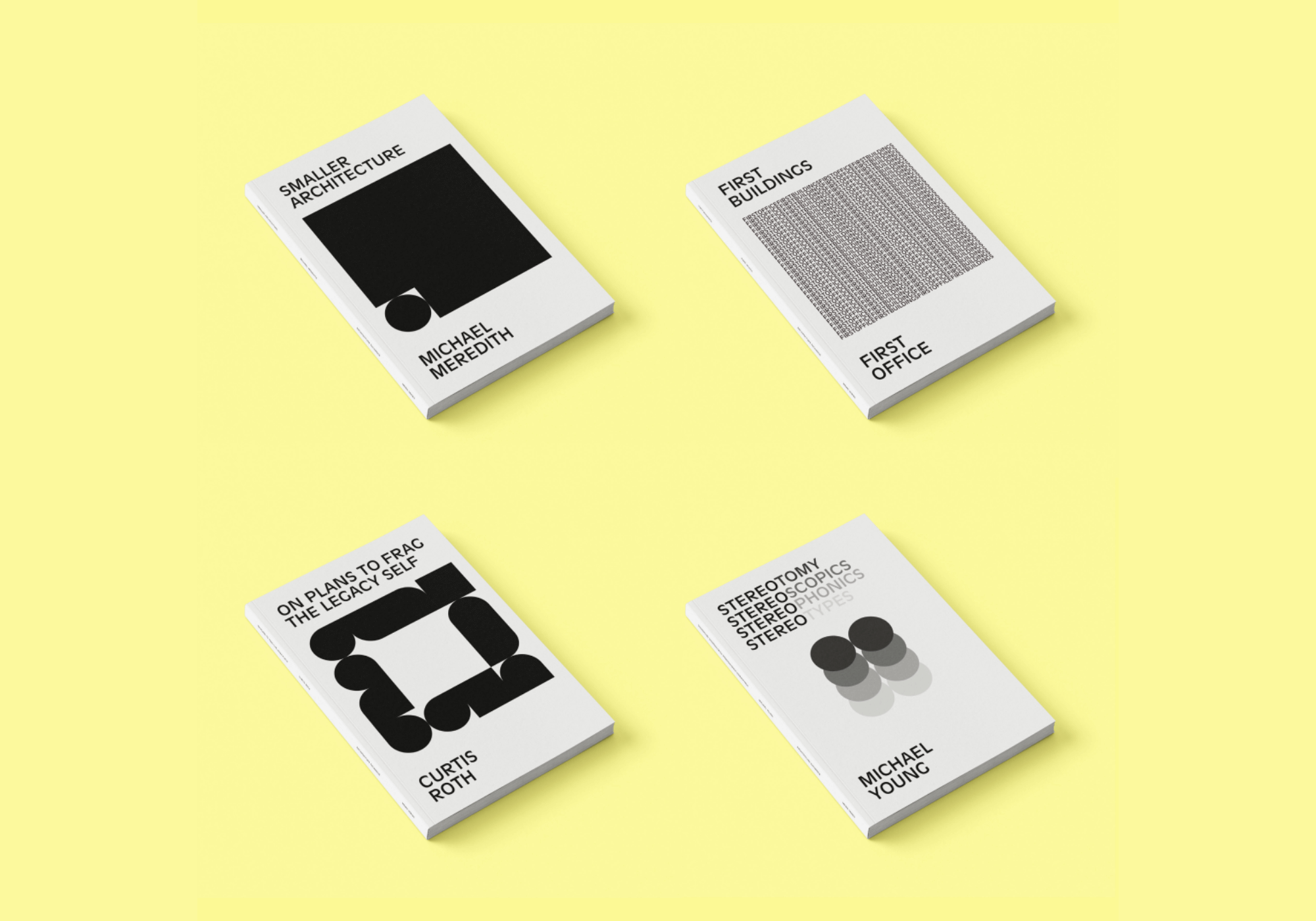

On one end of the spectrum came the small-book revival. Architecture Exchange launched Memo, a series explicitly chasing “small, cheap, and elegant little books” that can actually circulate, especially among students and early-career practitioners. These pocket-sized publications framed “smallness” not as austerity but as political positioning. Against bigness, against extractive ambition, and against theory that can’t leave the studio.

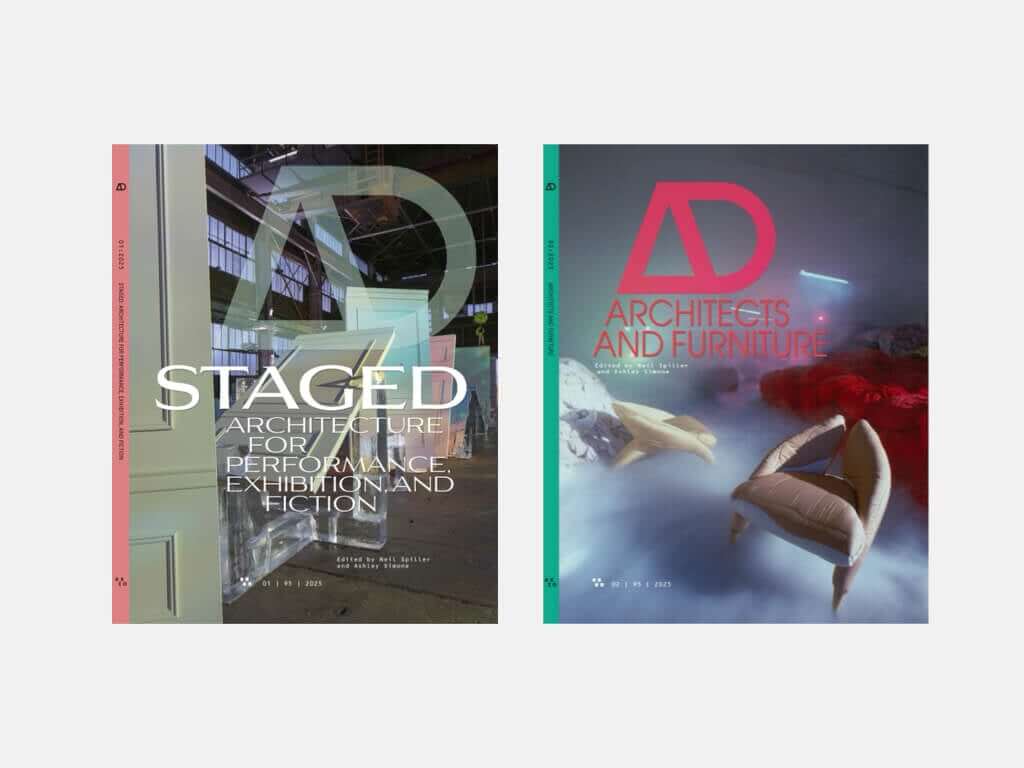

Meanwhile, legacy media didn’t retreat. Axiomatic Editions (Axio) took over Architectural Design (AD) from Wiley, with Ashley Simone as Editorial Director and the move reads like more than a change-of-hands. AD keeps its historic reputation for tracking avant-gardes, but the new era was pitched as more explicitly social/cultural/environmental, with fewer issues per year and a multi-channel expansion to broaden the audience beyond academia.

Then there was Los Angeles. Of the Moment (OTM), a folded, black-ink newsprint publication instigated by Thom Mayne and supported by the A&D Museum. It came onto the scene, positioning itself against snarky criticism in favor of conversation, scene-setting, and local allegiance. The fight was: do architects need critics or cheerleaders right now? In 2025, architecture media wasn’t asking what should we say, so much as where, how, and for whom should we say it? The answer, increasingly, was to try a new container and see who shows up.

Buildings found a beat

Gap dropped Parker Posey into Eric Owen Moss’s unruly (W)rapper building, turning a polarizing, partly vacant office tower into a late-’90s dance floor. Shot like a love letter to late-’90s Gap ads, the video treated the building less as a monument than as infrastructure for movement, with its steel tubes, mezzanines, and vacant expanses becoming props in a video.

Meanwhile, Bad Bunny’s “NUEVAYoL,” directed by Bronx-born photographer Renell Medrano, transformed Meister Hall, Marcel Breuer’s Brutalist landmark at Bronx Community College, into a cinematic stage where pastel styling, protest imagery, and concrete modernism collided.

Released on July 4, the video folded architecture into politics, draping monuments with resistance and reframing Brutalism as both seductive and defiant, even flashing a rejected fake apology from Donald Trump. The two moments showed that if architecture is struggling to assert relevance on its own terms, pop culture is more than happy to give it choreography.

Architecture, now loading

If it hadn’t already, in 2025, architectural discourse decisively left the page and moved onto the phone screen. Across Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube, design culture became faster, looser, and more personality-driven, with critique, history, and professional advice delivered as reels, explainers, and memes rather than essays or monographs. What once circulated through journals, conferences, and syllabi now travels algorithmically reaching audiences far beyond the discipline’s traditional consumers.

This shift played out on two fronts. Early-career designers and students—among them Maria Ulashchenko, Mikayla De Gouveia, Lachie McKern, Sana Tabassum, Juan Goya, and Kyara—used social platforms to document process, precarity, and becoming an architect in public. At the same time, mass educators and critics like Dami Lee, Stewart Hicks, Diana Regan, Cathal Crumley, Nino Ferrari-Mathis, and Dan Rosen translated architectural history, urban politics, and design criticism into entertaining, accessible formats. Together, they marked a year when architecture stopped waiting to be published and started scrolling.

This year made clear that architecture’s future public life will be shaped less by who controls the canon than by who controls the platforms where buildings are watched, shared, argued over, and absorbed.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper