Furnishing Fascism: Modernist Design and Politics in Italy by Ignacio G. Galán | University of Minnesota Press | $35

There are many endings in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1962 film, L’Eclisse. The most celebrated of these—the final seven-minute montage where Antonioni’s restless camera pans and cuts through the buildings and parks of Rome’s EUR district—stands as Antonioni’s most architectural gesture: a vision of a fragmented city beneath the honeyed gaze of a setting sun. The few figures who remain in this suffocating emptiness cast nervous glances skyward, hurrying home in search of light to escape the encroaching darkness. Here in Antonioni’s twilight Rome, the sloe-eyed Vittoria (Monica Vitti, embodying devastating languor) has ended her affair with Piero (the smoldering Alain Delon), a stockbroker whose demeanor mingles the feral with the inviting. Their final encounter precedes film’s tense montage of urban tableaux. Day surrenders to night. Buildings dissolve into the darkening sky. Streetlights flicker to life while Giovanni Fusco’s piercing, hammer-like forte piano chords amplify the slow-burning dread—a city drained of life in the grip of an ending.

This dread resonates so deeply because L’Eclisse functions as much as a study of interior lives as of architectural interiors. The film’s opening sequence establishes this dual focus: We witness Vittoria ending her relationship with Riccardo, a writer who commissions translations from her. Though little dialogue passes between them, their surroundings speak volumes. Riccardo’s carefully appointed home becomes a character, demanding its own inventory of objects, artworks, and furnishings. The accumulation tells us that here is the unmistakable domain of an educated, politically savvy urbanite. And later, we follow Vittoria to her own residence in an apartment block designed by Michele Valori, Leonardo Benevolo, and Giampaolo Rotondi. There she recounts her day to her friend Anita before both women visit their neighbor Marta, an English-speaking white colonialist whose apartment—also by Valori, this time in collaboration with Hilda Selem—serves as a shrine to her colonial past: Recently returned from Kenya, Marta has adorned her walls with photographs of Eastern Africa and filled her space with various curios and artifacts, including a glass table supported by a base fashioned from a taxidermied elephant’s foot.

These carefully catalogued objects and interiors represent what architect and historian Ignacio G. Galán identifies as arredamento in his new book, Furnishing Fascism: Modernist Design and Politics in Italy. Arredamento is a term that encompasses both “a single piece of furniture” and “the ensemble of elements that furnish a unified space, an interior,” while extending in practice to include industrial design and decorative arts. For Galán, the interwar Italian logic of arredamento offers an opportunity to revisit familiar figures from Italian architectural modernism—Gio Ponti, Lina Bo Bardi, Carlo Mollino, Eduardo Persico, Carlo Enrico Bava, and others—as major participants in a thriving public dialogue about interior design.

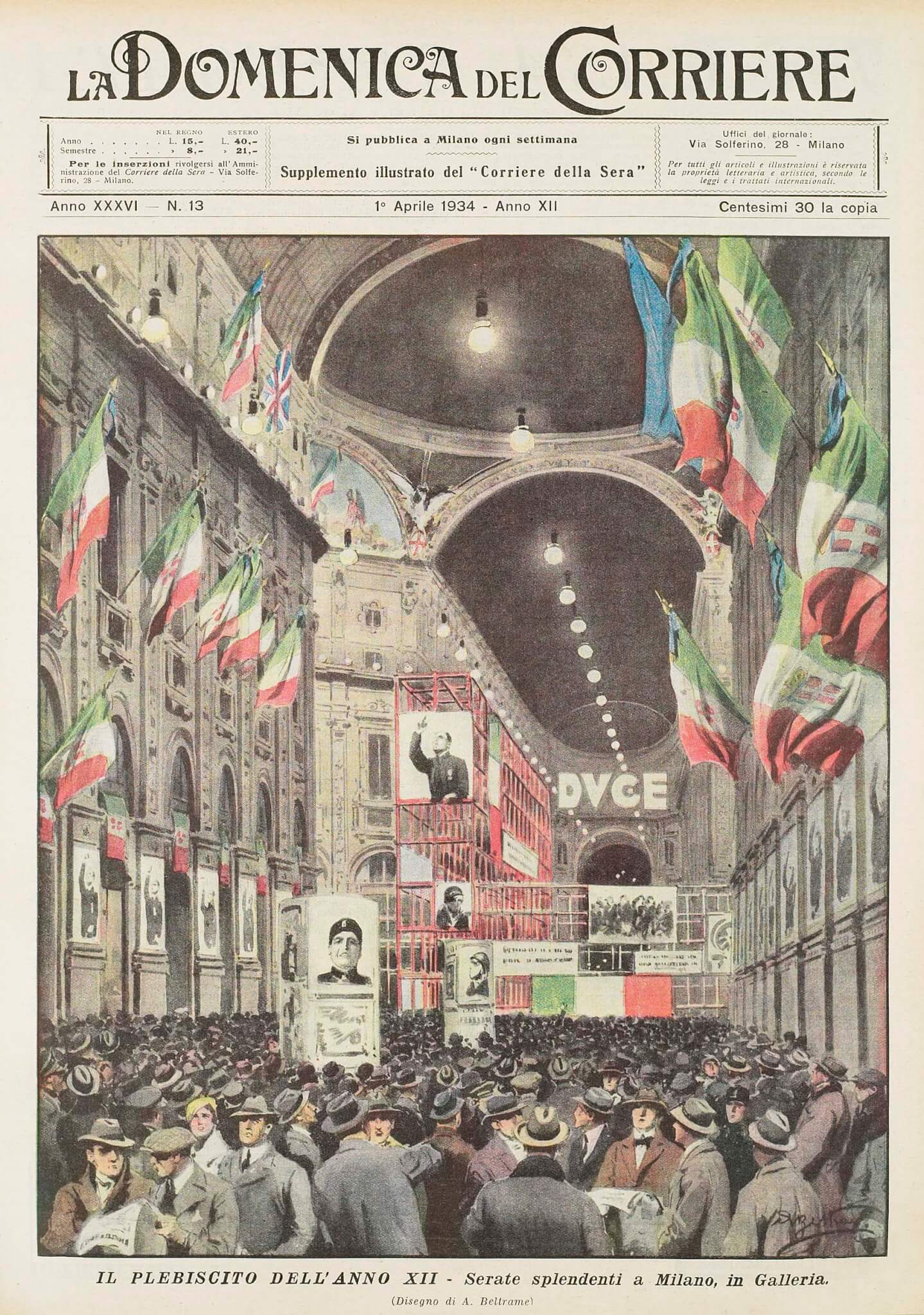

In the book, we read how this conversation played out across multiple venues: in the pages of publications like Casabella and Domus, exhibitions and films produced in the fabled Cinecittà Studios, homes along the Mediterranean coast, and even the design and display of domestic interiors intended for settlers in Italian East Africa. And as one can guess by the book’s title, it turns out that each of these venues sublimated the architectural interior into a mechanism for communicating national (and nationalizing) aspirations into something legible and consumable—or as Galán tells us, instances of how “furnishing coordinated the emphases of modernist design with the project of fascism.”

Architecture as Coordination?

“Coordinated” proves a curious turn of phrase, suggesting that without arredamento, the realms of modernist design and interwar politics remained at a distance—hardly connecting, sometimes occluding each other. Galán portrays arredamento as a kind of intellectual prologue to fascism. In this sense, furnishing became a way to link design “to the idealized values of civiltà (national identity)” as well as “a medium to advance the processes of national regeneration that led the project of fascism.” Though Galán rightly claims that the interrelations between design and politics in interwar Italy were multidimensional and not necessarily explicit, Furnishing Fascism may inadvertently ascribe false agency to arredamento‘s “coordinating” role. One reason for this lies in Galán’s decision to limit his scope of inquiry to media discourses concerning furnishing and interior design.

Furnishing Fascism is a finely written, compelling, and thorough analysis of the language of furnishing—of how design publications aimed at both highbrow and mass audiences argued for the civilizing spirit of something as ordinary as a chair. Yet one hazard of publication-based discourse analysis is its almost exclusive focus on authors’ inner logics or editorial intent. Throughout Furnishing Fascism, we receive an incomplete picture of the lives of articles published in Casabella or Domus. A welcome reception is assumed, meaning we rarely encounter criticism levied against the book’s major actors. It would take considerable imagination to envision a world where cultural discourse moves and propagates as if through smooth, isotropic space freed from obstacles and restrictions. This may be far from the world of Furnishing Fascism, yet any sense of how arredamento landed outside known, well-defined circles is absent.

We are meant to understand arredamento as a design strategy of practice, but when subjected to discourse analysis, it is tempting to treat it as a theory of design in the same capacity as its contemporary fellow traveler, razionalismo (rationalism). This shift brings hazards, particularly when Galán writes that “seemingly neutral everyday furniture items and the allegedly minor arts played a major role in shaping Italy’s identity at the scale of the household and enacting the regime’s politics during the Mussolini era.” The difficulty lies in finding any histories that contradict the claim that furniture was passive or “neutral everyday”—and no field of historical inquiry exemplifies this better than scholarship dedicated to design and politics in interwar Europe.

The rich body of work arguing this exact point is vast. Consider Jeffrey Herf’s Reactionary Modernism: Technology, Culture, and Politics in Weimar and the Third Reich (1984) or Anson Rabinbach’s discussion of the Amt Schönheit der Arbeit (Bureau of Beauty of Labor) in The Eclipse of the Utopias of Labor (2018). The Bureau, created in 1934 by the Nazi workers’ association and the German Labor Front, promoted the beautification of industrial interiors. Even Sigfried Giedion, that erstwhile promoter of modernism, claimed in Mechanization Takes Command (1948) that an “anonymous history of our period” reveals “our mode of life as affected by mechanization—its impact on our dwellings, our food, our furniture.”

This discourse is further evidenced in Michael Thad Allen’s The Business of Genocide: The SS, Slave Labor, and the Concentration Camps (2005) or Jean-Louis Cohen’s wide-ranging analysis of design’s multiple scales in Architecture in Uniform: Designing and Building for the Second World War (2011). The results of such research still manage to surprise and shock. Consider architectural historian Nader Vossoughian, who in the June 2022 issue of the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians examined how the Nazi Institute for Standardization’s Construction Standards Committee, presided over by Ernst Neufert, served as the main intellectual and professional inspiration for the Finnish Standardization Office, established by architect Alvar Aalto in 1942. Through deep analysis of standardization in Finnish architecture journals and trade publications during the Second World War, Vossoughian concluded that the Finnish Standardization Office “was nothing if not a mechanism through which to normalize trade relations between Finland and Germany. It was dangerous precisely because it was part of an intricate and, at times, imperceptible global infrastructure that furthered the Nazis’ destructive aims.”

The Apparatus of the Interior

Galán’s central assertion throughout Furnishing Fascism—that furniture design held an important presence in discussions about national identity—remains well-taken. This holds true even though our understanding of that design comes filtered through photographs and written pieces published in magazines. When it comes to analyzing the role that film sets played in this discourse, however, the issue of representation becomes more problematic. Galán ascribes a kind of anthropomorphic agency to pieces of modernist furniture and the films in which they are featured. They “perform,” he argues. But what exactly does this mean? How does a film “perform”?

We might turn to the work of film theorists like Jean-Louis Baudry, Christian Metz, and Jean-Louis Comolli—key figures in what became known as “apparatus theory” in film studies—to consider how all aspects of filmmaking contribute to a film’s meaning and effect. For apparatus theorists, cinema functions as an ideological mechanism that shapes spectators’ perception of reality through its technical and institutional structures. The camera, projection system, editing techniques, and even the darkened theater itself work together to create what Baudry termed the “basic cinematographic apparatus”—a system that produces specific subject positions and ways of seeing. In this framework, films don’t simply represent reality; they actively construct it through the technological and social apparatus of cinema itself. The furniture within film sets, then, would participate in this broader ideological work, not through autonomous “performance” but as elements within cinema’s complex representational machinery. And this is something that Galán tacitly acknowledges when, in a nod to Baudry, describes the process of how “film converged with modernist furnishing under Italian fascism as an apparatus.”

As compelling as this, it presents us with an incomplete picture of the Italian filmmaking apparatus because we are only looking at a handful of films whose explicit “convergence” with architecture is mediated through known figures like Carlo Mollino and ancillary discussion in film and design journals. In other words, a more nuanced discussion on actual apparatus-ness of the apparatus is missing. It is a missed opportunity to cast filmmaking as a principal organ in disseminating the logics of arredamento.

Rather than focusing on the ways in which films “performed,” it proves more productive to consider how Italian cinema constructed the logic of arredamento. The architectural metaphor may seem facile, yet it yields significant insights. Consider Michelangelo Antonioni’s documentary Gente del Po (People of the Po Valley), completed in 1957. With its sumptuous framing of natural and built landscapes, this film, Antonioni’s first, stands as an aesthetic precursor to his later masterworks: L’Avventura (1960), Il Deserto Rosso (Red Desert) (1964), and L’Eclisse (1962). Yet Gente del Po began life in 1939 as an article titled “Per un film sul fiume Po” for the journal Cinema. As film scholar Noa Steimatsky has demonstrated, the article reveals the populist-humanist and regional-modernist tensions that characterized art in late-Fascist culture—concerns equally central to Furnishing Fascism. Antonioni’s Gente del Po imbues the landscapes of the Po Valley with a distinctly national and modernizing aesthetic that foregrounds the actual “gente” of its subject. Examine the images of cinematic interiors in Galán’s book: Those taken from films teem with life, while the photographs published in design and professional journals are notably devoid of human presence.

The cinematic dimension of Furnishing Fascism merits more sustained engagement. Galán’s sensitive analysis of cinematic interiors proves compelling as one of the few recent works to bridge architecture and cinema as practices emphasizing both design and construction. (One recalls that in Italian film production the production designer is typically designated “architetto.”) The most persuasive argument for how cinema and photography can “construct” architecture appears on page 134 with Carlo Mollino’s plan of the Casa Miller in Turin for a 1937 issue of Domus. Inscribed within this conventional architectural plan lie various arrows corresponding to camera positions, a device reminiscent of the directional cues in Herbert Bayer’s floor plan for Bauhaus 1918–1928 at MoMA, Alfred Hitchcock’s continuous single-camera shot threading through a Manhattan apartment’s interior space in Rope (1948), or Guy Debord’s Naked City: Illustration de l’hypothèse des plaques tournantes en psychogéographique (1957), which imagines a psychogeographic Paris whose disparate neighborhoods are stitched together with red arrows. Such devices ultimately remind us of Antonioni’s own characterization of Gente del Po not as documentary, but as narrative.

Arredamento Abroad

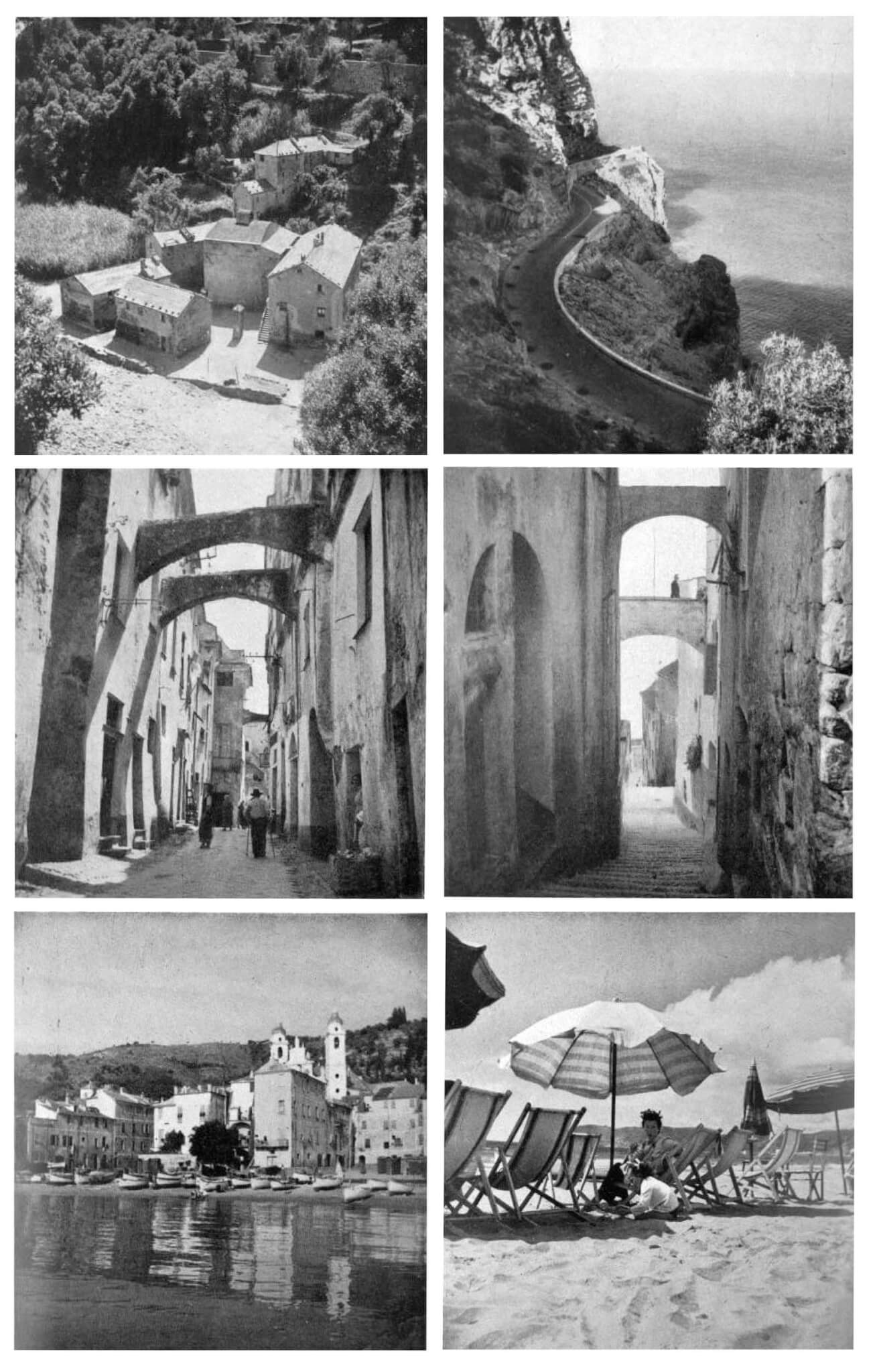

Yet arredamento’s significance extended well beyond the confines of cinematic representation. Far more than a civilizing presence, it was crucial to the creation of a regional and colonial identity—even though the internal pressures to create a legible and localized Italian identity threatened to undercut global aspirations. Both colonialism and tourism endowed arredamento with a distinctly mobile quality, transforming Italian design into a portable cultural ambassador that could adapt to diverse contexts while maintaining its essential character. This mobility, however, created a paradox: Italian culture found itself running to stand still, desperately seeking to gain a foothold in a world that kept shifting and changing under the pressure of an oncoming global conflagration.

In the final passages of Furnishing Fascism, Galán demonstrates how designers navigated this unstable terrain by imagining both a Mediterraneanized version of civiltà that repurposed historical buildings and an exportable version that portrayed a new kind of domestic life in East Africa. The tourist villas of the Italian Riviera required furnishings that could speak to international sophistication while remaining recognizably Italian; the colonial settlements of Eritrea and Ethiopia demanded designs that could project metropolitan authority in landscapes thousands of miles from Rome. This geographic dispersal meant that arredamento had to function simultaneously as anchor and vessel—grounding Italian identity while enabling its circulation across an increasingly volatile world. In other words, arredamento became indispensable to reimagining the past, present, and future of Italian identity precisely because that identity could no longer remain stationary in the face of global upheaval.

Addressing Fascism Itself

There is nevertheless an unresolved tension throughout Furnishing Fascism. On one hand, Galán situates his observations within a larger constellation of discourses about art, architecture, and design in Fascist Italy. By focusing on the significance of a single concept—arredamento—the book presents readers with a kaleidoscopic reading of design that refracts the project of Italian Fascism into disparate shards, each with its own discourse and cast of players. On the other hand, Galán’s effort to add nuance and depth to the historiography of design in Mussolini-era Italy deflects from more critical approaches to the existing literature and, more crucially, from any penetrating commentary on the nature of fascism itself.

Clearly, Furnishing Fascism is not a book about complicity or about how modernist discourse found an accommodating vessel in Fascism—territory covered admirably by a generation of scholars including Romy Golan, Jeffrey Schnapp, and David Rifkind. Instead, Galán offers fascinating conclusions about how historical understandings of furnishing are woefully outdated while posing broader questions about how the logic of furnishing might apply to our contemporary moment. It is as if Galán stops short of asking harder questions about the relationship between architecture and power, and like Lidia Levi, the matriarch of Natalia Ginzburg’s 1963 novel Lessico famigliare (Family Lexicon), merely observes: “Let’s see if fascism will last for a while.”

We return, then, to those emptied streets of Antonioni’s EUR district, where architecture and objects speak in the absence of human voices. The challenge that Furnishing Fascism poses—and perhaps inadvertently sidesteps—is how to read the ideological weight of domestic spaces without falling into the trap of treating them as autonomous actors. The book’s title inevitably recalls Susan Sontag’s 1975 essay “Fascinating Fascism,” published in the New York Review of Books as a critique of cinema’s attempts to rehabilitate Leni Riefenstahl’s work without acknowledging her Nazi past. Sontag’s warning about the aesthetic seduction of fascist imagery resonates here: The danger lies not in the objects themselves but in our willingness to admire their formal qualities while remaining blind to their complicity in systems of oppression.

Contemporary cinema continues to grapple with this question. Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest (2023) offers a stark reminder that interiors still demand interrogation, presenting the domestic realm of a Nazi commandant’s family home as a space where the most mundane furnishings—a child’s toys, a kitchen table, garden furniture—become complicit in unspeakable horrors occurring just beyond the garden wall. Like Antonioni’s architectural fragments, these objects require us to look beyond their apparent neutrality and examine the systems of power and ideology within which they operate. The work of understanding how spaces and their contents participate in broader historical projects remains as urgent as ever.

Enrique Ramirez is Visiting Associate Professor at Pratt’s School of Architecture and Adjunct Associate Professor at Columbia University GSAPP.

This post contains affiliate links. AN may have a commission if you make a purchase through these links.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper