Design Against Racism: Creating Work that Transforms Communities by Omari Souza and contributors Zariah Cameron, George Fourlas, Shimika Klassen, Daniel Lake, Cassini Nazir, Lesley-Ann Noel, Yolanda Rankin, Soniya Robinson, Kaleena Sales, and Lauren Williams | Princeton Architectural Press | $24.95

In Design Against Racism, Omari Souza and his contributors have compiled a primer on racism and design for those who are new to the United States’s specific brand of structural racism and its codification through design and architecture. Souza has curated a collection of 33 mini-essays that condense scholarly concepts, share personal stories, and offer advice on practicing antiracism in design. The book is organized into three sections: History, Practice, and Case Studies. With this handbook Souza aims to provide a resource to architecture students and professors looking to reshape design pedagogy, as well as architecture practitioners who work with Black and brown communities. Perhaps in a different universe, the book would be mandatory reading across design classrooms, a signal of a structural change following the “racial reckoning” that followed the murder of George Floyd in 2020. As it is, in our present universe in 2025, words like “racism” and “equity” are officially banned by the Federal Government. Instead, it must find its audience among those of us who are still brave enough to want to learn how to practice restorative design, which the book defines as “an approach to design that centers on healing, inclusivity, and equity by addressing and repairing past harms inflicted on marginalized communities.”

Reframing Histories of Racism

In the History section of the book, nine essays by Souza and one essay by George Fourlas highlight ten conceptual flashpoints in the United States’s distinct structures of colonial and anti-Black racism. The author’s approach to history is anthropological in that it does not list strings of facts, but rather focuses on the nuanced descriptions of one’s own communities as modeled by anthropologists like Zora Neale Hurston and William Cunningham Bissell who are referenced in the book. The brevity of each chapter indicates the author’s desire to make the topic accessible, however for many of its target audience who might already be familiar, these summaries might feel surface-level and basic.

The first few chapters condense the scholarship of key concepts such as Eurocentrism (Fourlas’ contribution), the white gaze, and colonial nostalgia. Souza and Foulas ground these concepts within specific place-based histories of anti-colonial history and thought: Europe itself, Zanzibar in Africa, and the island of Martinique in the Caribbean.

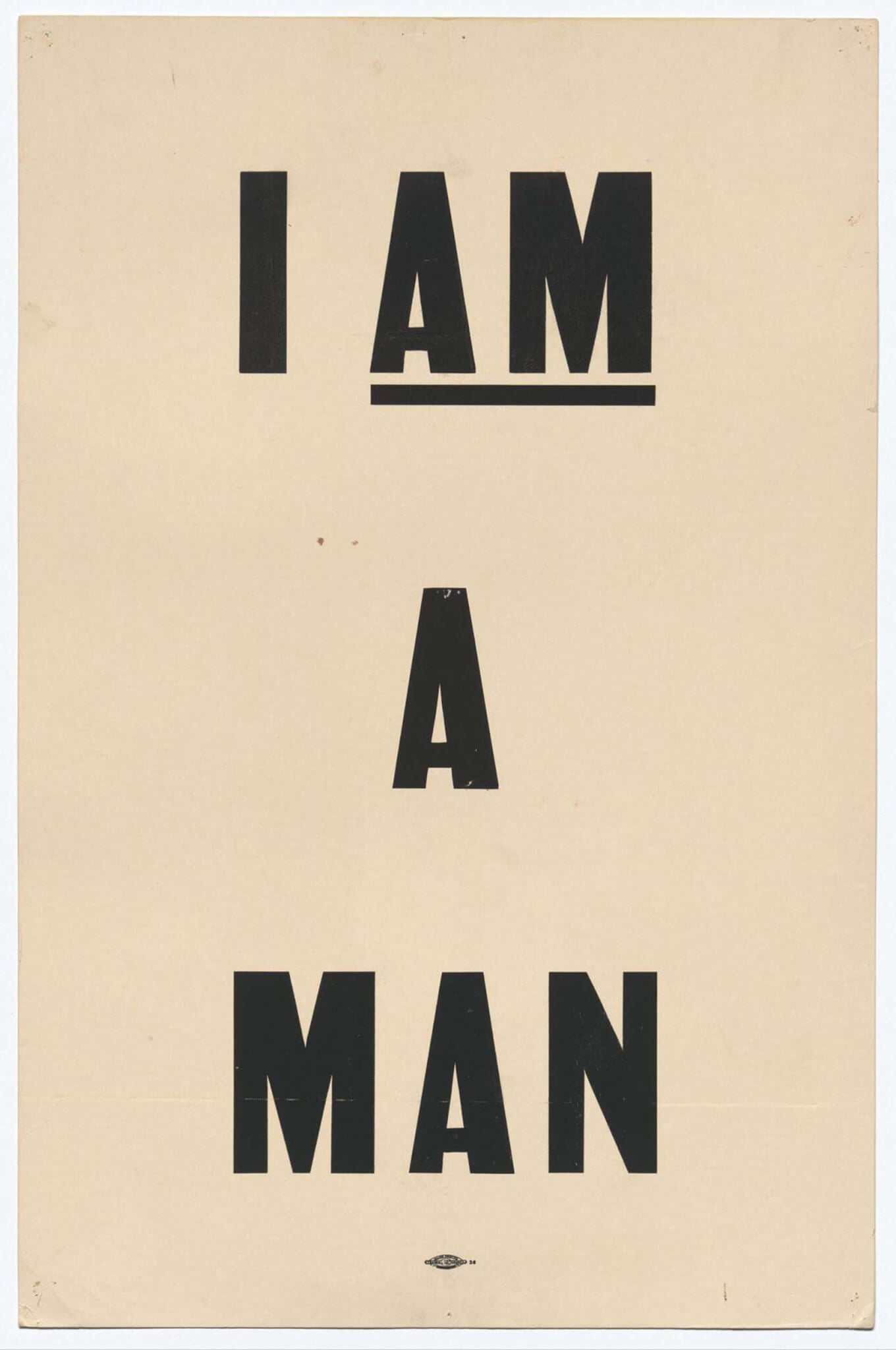

The next chapters highlight the reclamation of spoken and visual language by African Americans in efforts to re-story themselves as subjects, not objects, in the United States. Topics include the history of the “I AM A MAN” sign as part of the Black Sanitation Workers protest in 1968 and Kenneth and Mamie Clark’s Doll Test in 1947, which revealed that both Black and white three to seven years old children attribute negative associations to Black skin, and its recreation by Toni Studivant in 2017.

The History section concludes with a focus on two examples of the deep intersections of racism and spatial design in the United States: first, redlining’s discriminatory history as an instrument for limiting Black homeownership and investment in Black neighborhoods, and second, the mortal danger of sundown towns. Souza uses the existence of sundown towns to showcase the creation of the Negro Traveler’s Green Book, which helped Black travelers navigate the United States by creating a networked list of safe places to eat and rest.

In his retelling of design histories in this first section of the book, Souza makes a clear case for how racism is reproduced through design. However, to serve as inspiration for the next generation of designers, he also points toward examples of how marginalized communities have historically countered such harmful designs with solutions and alternatives that not only ensure survival but also foster joy.

Anti-racist Practices of Self and Community Care

So, what does it look like to be an anti-racist designer? In the Practice section, readers are offered reflective and practical advice on how to incorporate anti-racist and restorative approaches into their own creative practices. The advice comes from a wide range of global contributors besides Souza, including Leslie Ann Noel, Cassini Nazir, Sekou Cooke, Shimika Klassen, Kaleena Sales, and Zariah Cameron. The fifteen mini-essays cluster into three domains of restorative practice: storytelling, community building, and spatial design.

The chapters focused on restorative storytelling feel abstract and focused on tools of self-reflection. They outline important strategies such as acknowledging past harms through reconciliatory interventions, such as a Holocaust “Survivor Café” and South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and reframing storytelling POVs to be inclusive of those with less power.

Although power is mentioned, little is said on how to actually fight, for example, the power structures of media consolidation and digital censorship to platform restorative stories. This information requires greater urgency, especially when institutional support has waned or is even openly hostile to these restorative narratives in recent years.

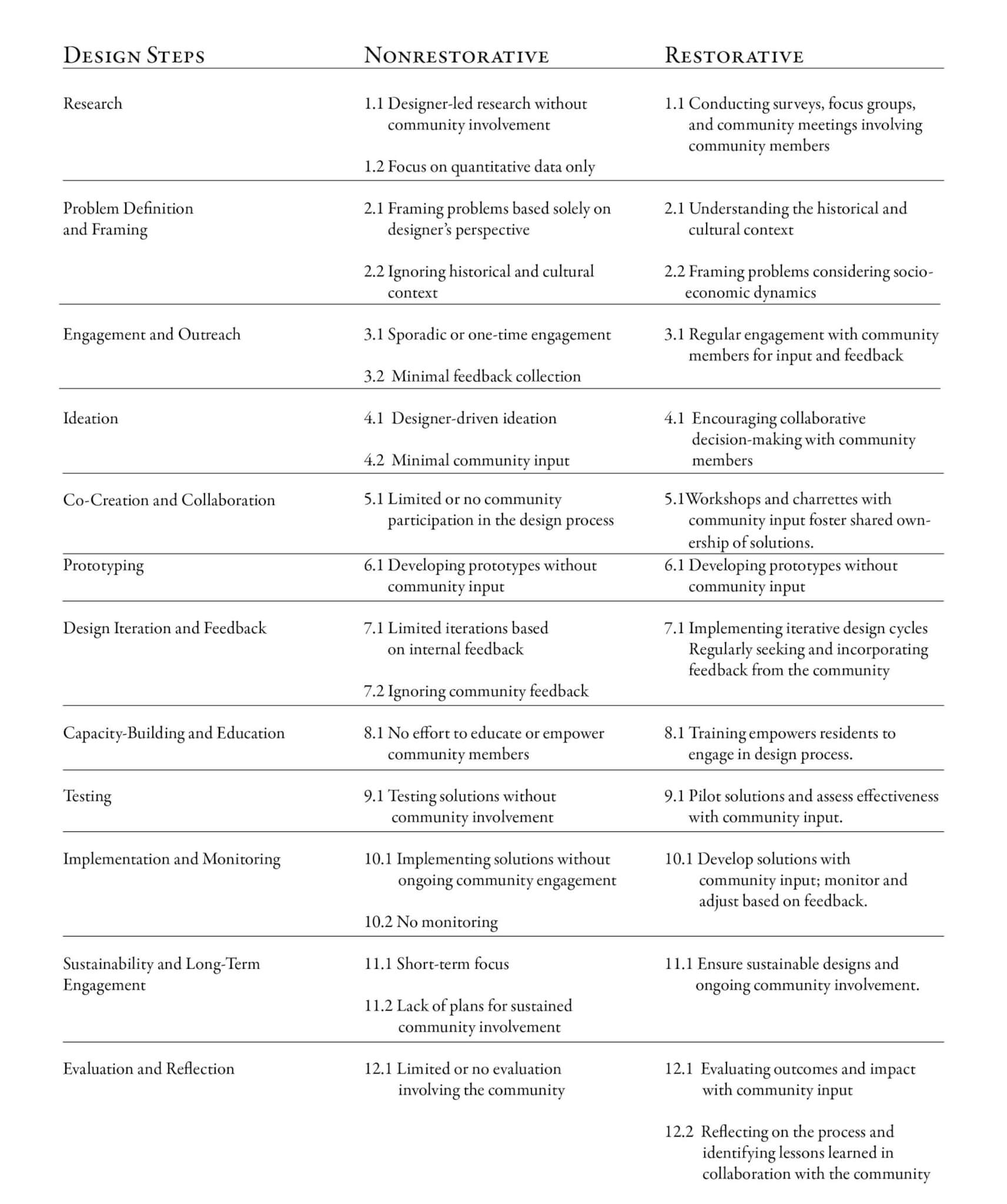

The chapters focused on restorative community building are more grounded in the dynamics of power and relationships. Cassini Nazir addresses the limitations and possibilities of empathy as “curiosity and care.” Noel provides tools to knowing your own positionality (i.e. how who you are can determine the story you tell about the world). Souza offers a chart representing the Spectrum of Approaches to Community Design, which clearly lists what a design process looks like with or without community input. What is missing in the restorative community chapters is advice on figuring out compensation and legal intellectual property ownership, which are often key areas where community partnerships fail.

The last five chapters draw upon a wide range of Black authors who highlight different aspects of restorative spatial design practices. The reader gains a broad exposure to Black values, as expressed through cultural forms like hip-hop, quilting, and collage. The design examples selected, such as the National Museum of African American History and Culture by David Adjaye or the collages of Marryam Moma, show how the application of Black values to design and architecture restores Black minds and bodies through the self-representation of Black resilience and joy.

Case Studies in Restorative Design

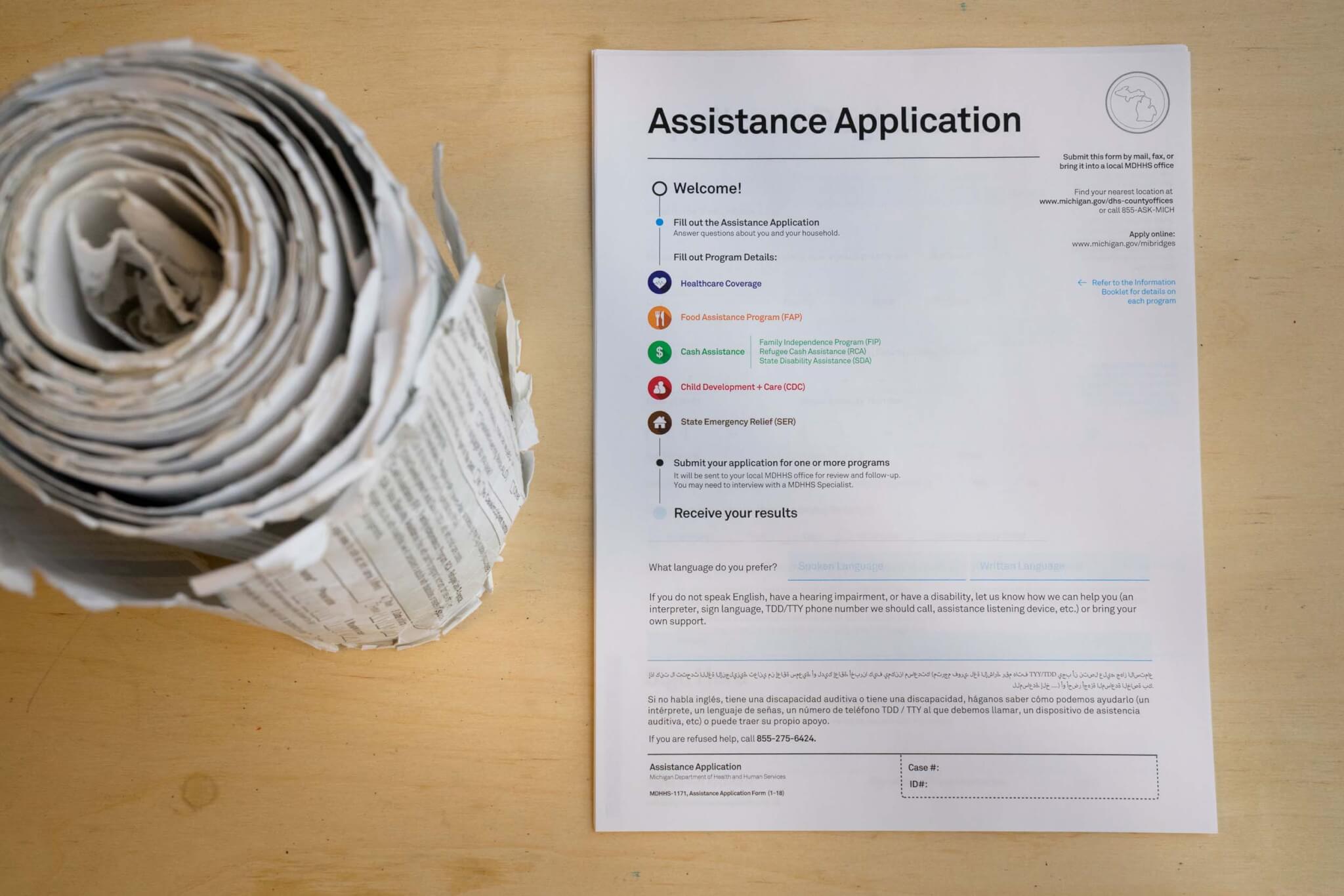

Souza and his collaborators close out the book with eight examples of how educational institutions, non-profit studios, and community organizations are practicing restorative design. The highlighted projects are success stories, illustrating what restorative design looks like in the field. While the brevity of chapter format worked well for the first two sections, it does disservice to each project’s complexity in the Case Studies section. I desired more depth about the set up and impact of each project. For example, the Civilla project worked for three years with Detroit residents and government administrators to transform a 40-page public benefits application form into something shorter and easier for people to use. However, key questions remained in the book’s analysis, such as why the organization had to independently fund the preliminary research with community or how much shorter the final form ended up being. These details are important for understanding the replicability of success in a restorative design process, especially for young architects and designers who want to build restorative design practices.

Yet, I appreciated Souza ending the book with the case studies. The reader leaves feeling good about the real unity and cohesion of a restorative design approach. It is clear how restorative design should be expanded in design education to correct for the imbalances of Eurocentric perspectives in the curriculum, such as the Bauhaus.

In today’s political climate, Design Against Racism is even more crucial to read. Black, immigrant, and Indigenous peoples, women, the LGBTQ+, and the disability communities are being systematically harmed by policies seeking to exclude and erase them in the United States. I hope that when the present harms have passed, as they surely will, Souza and his contributors have already laid out for us the frameworks for the restorative design necessary to rebuild our communities.

Dori Tunstall is an award-winning design anthropologist and author, who consults with organizations seeking to practice liberatory joy in their work with cultural communities.

This post contains affiliate links. AN may have a commission if you make a purchase through these links.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper