Shade: The Promise of a Forgotten Natural Resource by Sam Bloch Random House | $32

The first cities were not heat islands, but the opposite: shady oases that provided refuge from the blazing Mesopotamian sun. Here in the New World, from Indigenous adobe homes to California Craftsman bungalows and breezy Louisiana shotgun houses, “American builders used to be climate control experts,” Sam Bloch writes. So why, today, is it impossible to find shade along many urban thoroughfares? Shade can mean the difference between comfort and misery, or even life and death. It invites us to linger and interact. In Shade, an enjoyable and persuasive read, Bloch, an environmental journalist, argues that shade is an overlooked “natural resource” and fundamental human right that can help us survive a warming planet and revitalize the urban public realm.

Leveraging scientific data and colorful anecdotes, Bloch proves that shade is far more important, delightful, and elusive than I, for one, had considered. We humans are just like salmon and squirrels and cows and bugs in that, in summer, we mostly choose shade when we can. We differ in that we also design for shade—from sombreros to arcaded cities—but we have forgotten our old tricks for collective outdoor shade tolerance, at least in the U.S. Our default reliance on private air-conditioned cars and homes has left the public realm inhospitable and dangerous, especially for vulnerable populations. It’s also weakened our bodies’ ability to adjust to hot weather, Bloch says. The good news is that all this is reversible— not through architecture alone, but through design coupled with policy moves and different cultural expectations.

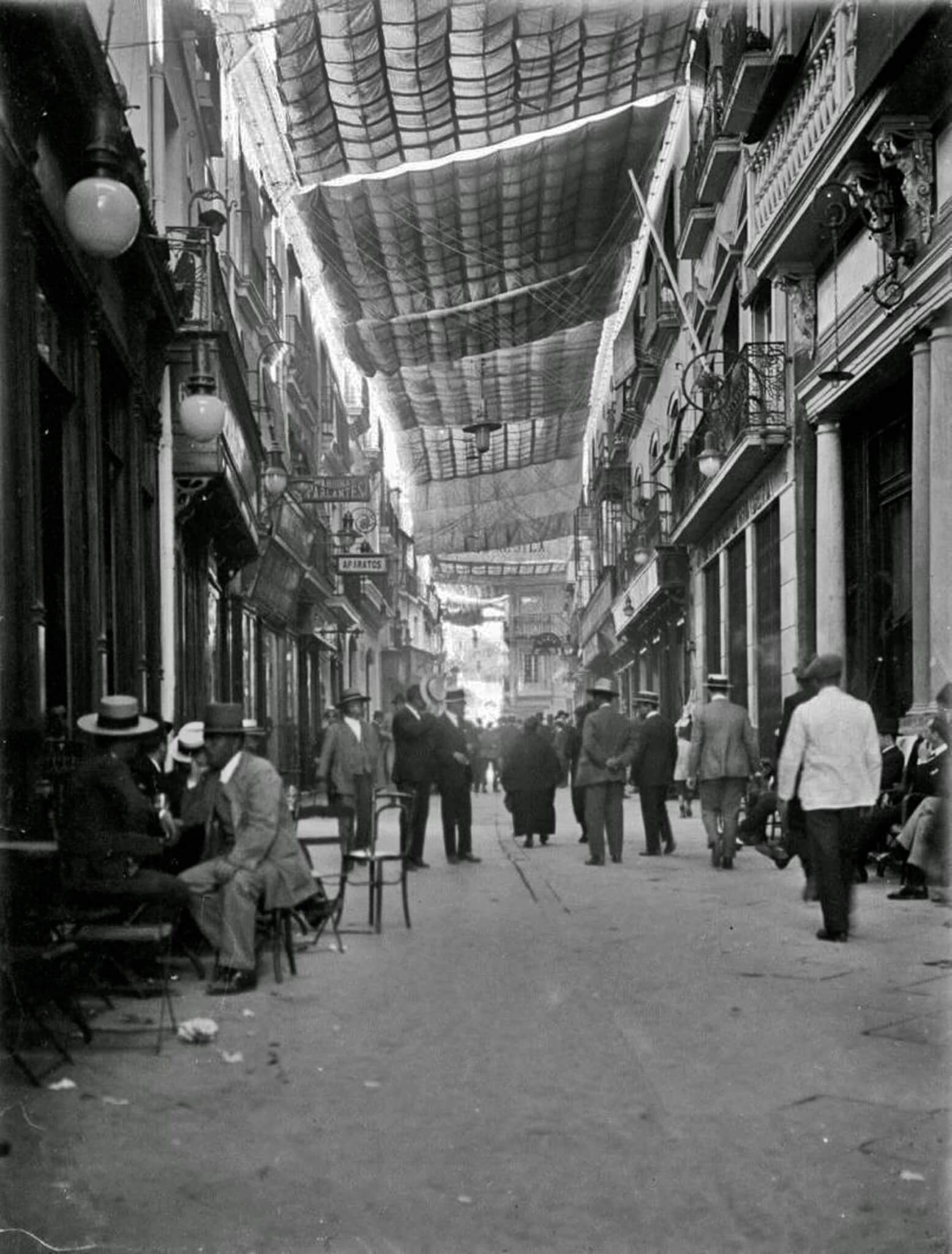

Bloch takes us from shade-starved, mercilessly exposed bus stops and streets in Los Angeles, where he lived for a time (in one of the city’s “shadiest,” i.e., most privileged, neighborhoods, he admits), to older cities in sunny climes. The tall, canyon-like alleys of Fez, Morocco, “blockade” cool air near the ground, whereas the arcaded portici of Bologna, Italy, protecting more than 24 miles of street frontage, create a breeze from the differential temperature of shaded walks and unshaded streets. Contemporary Singapore has its covered sidewalks, which Bloch calls an “urban lubricant” because they catalyze social and economic activity in steamy weather. Barcelona has its crazily popular green streets. But in Los Angeles, Bloch reports, shade is effectively “illegal” on arteries like Figueroa Street, where thousands of people wait for buses on scorched sidewalks deemed too narrow for shelters, trees, or even vendor umbrellas. That’s why shade is not strictly an architectural or landscape design problem, according to Bloch. It’s also about culture, politics, and social equity. In Australia, following a generation of public service announcements about the dangers of sun exposure, people “have come to believe that everyone should be able to access shade.” More than 80 percent of public playgrounds in New South Wales are now shaded by trees or sails, Bloch reports, whereas only about 33 percent of American playgrounds are similarly shaded.

Bloch does not think shade can replace air-conditioning when it’s extremely hot out, which is an increasingly urgent matter. But to cope with ordinary summer heat, he implores us to abandon our (North American, post-WWII, fossil fuel–enabled) comfort zone and relearn how to use shade, curtains, water, and ventilation. He describes a passive house in Portland, Oregon, that never warmed above 84 degrees during the 2021 heat dome, when outdoor temperatures soared to 116 degrees. Its builder and inhabitant, architect Jeff Stern, recalled living through those days in “light sweating mode.” Could mainstream American culture adjust to light sweating mode? Bloch says we should try by maximizing passive design options and limiting our use of AC to truly dangerous heat, thereby limiting carbon emissions that further warm the planet. Bloch realizes, of course, that places like Portland are quickly expanding air-conditioning capacity in response to the shock of hotter summers. But if city or state agencies worked together to incentivize shade in public realm design and private development, architects and landscape architects could spring into action.

Bloch’s favorite outdoor air conditioners are deciduous trees, which he fondly calls “communal parasols” and “misting machines that cool the air.” Miraculously, these shade towers automatically drop their canopy in the winter, letting the sun shine through. But he’s also enthusiastic about technological shade solutions like agrivoltaics—solar panels that partially shade crops—which stimulate higher yields and produce clean energy.

Bloch is a witty writer. I could not fathom how I was going to read hundreds of pages on this topic until I realized the author was committed to cranking out zingers: “If shade is as old as the Bible, so is the bias against it.” “Americans use more energy for cooling than the billion-plus people of Africa use for everything.” And Bloch’s science journalism sparkles. Early on, for example, he explains why shade feels good on a hot day, and it’s almost trippy to contemplate. “Shade soothes the senses. When the sun’s light is removed from bare skin, the infrared waves diminish and the agitated water molecules in our tissues begin to calm. They slow down, which cools them.” He brings the same verve to describing how Diébédo Francis Kéré’s passively cooled schools in Burkina Faso not only use shade and wind to “temper a hot desert environment” but also require that occupants know when to open and close windows and remember to refill buckets of water under windows to maximize evaporative cooling.

Toward the end of the book, Bloch zooms high above the clouds to explore the potential for controversial geo-engineering or “planetary shade” solutions involving solar radiation modification. The basic premise is to screen a fraction of the sun’s energy before it hits Earth and gets trapped in the atmosphere. There are many ideas about how this could be done, from blankets of gas to swarms of reflecting devices, but each of them could have unintended and uncontrollable consequences, Bloch says. And in our era of shady billionaires and self-serving politicians setting the agenda for space, such technology could be used for private advantage rather than public good.

Even back on Earth, shade is not equally distributed. Bloch wants to make sure there’s enough to go around. All we have to do is build and plant more shade infrastructure, not piecemeal but systemically, in “holistic, long-term plans for streets, parks, and playgrounds.”

Gideon Fink Shapiro is a critic and historian who spends a lot of time in public spaces.

This post contains affiliate links. AN may have a commission if you make a purchase through these links.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper