Lists like this are set up to fail, and, in line with the inevitable, this one fails too.

But we never kidded ourselves, nor intended to kid you, that we could succeed in definitively choosing the 40 greatest, most important, creative, and successful music makers in the last 40 years. Many great artists didn’t make the cut.

We did try to get this as right as possible, and, if it’s any consolation to you for your favorite artist that’s not on the list, no one was satisfied with the outcome.

I’d say we’re like a big, dysfunctional family, but the word “like” would be redundant. We argued and advocated, and internally there were those who wondered, for instance, why Bowie is on the list, when some say he peaked pre-1985, but Kendrick Lamar isn’t. The deciding view was that Bowie had not peaked and still made great music until his death in 2016 (literally up until the days before he died).

And please don’t think for a second this was all democratically arrived at! God no. That would be dull! There wasn’t much consensus on anything. Which, perhaps, is the way it should be -– because it was all about passion. Some passions prevailed, some didn’t. Some votes, ahem, counted for more than others, but SPIN has always been a banana republic. Proudly.

We started this in our first issue of the year, in spring, with numbers 40 – 31, and continued in summer with 30 – 21. So this is the big reveal!

On reflection, I think we came close…

Bob Guccione, Jr.

40 U2

U2 just make the cut-off because three fourths of the group aren’t pretentious twats and the one who is is a good singer. And they probably just about belong on this list for their audacious, almost supernatural ability to remain popular, and animate the illusion that they are relevant and fresh, without ever actually doing anything particularly very good. Their best, rawest, most interesting work was done before 1985 in my opinion, but since then they put out a couple of great albums, Joshua Tree and (better) Rattle and Hum, and a few good songs on other releases, although I can’t think of any except “Angel of Harlem”, which is truly masterful. So, you know, maybe that’s enough. – Bob Guccione, Jr

39 LAURIE ANDERSON

Ever since Laurie Anderson shot out of the New York downtown scene in 1980, she’s often seemed to be a code to crack, a puzzle to solve. The thing is, she gave us the formula right in plain sight on her very first album, the still-startling Big Science: “Let X = X,” she told us. Or, perhaps in not-too-buried subtext, “Let me be me.”

That she says this in a piece full of quizzical statements, context-deprived observations and decidedly quirky music that somehow manages to straddle pop and experimental minimalism without connecting with any pre-existing genres at all, underscores that individuality. This is the constant of a singular vision running through projects massive — the 1980s landmark multimedia extravaganza epic The United States of America — and intimate — 2015’s film Heart of a Dog, a moving portrait of grief in the wake of the death of her husband, Lou Reed, and their dog Lolabelle, and her most recent album, the affecting Amelia, inspired by doomed aviator Amelia Earhart, doomed voyages being a regular theme for her.

Comparisons are tough to come by, influences range from William S. Burroughs to John Cage to her friend Philip Glass, more philosophical than in specifics of her sound, per se, and to collaborators including Brian Eno, Reed and filmmakers Wim Wenders and Jonathan Demme. As for who she’s influenced, that’s even tougher. No one can do her sound, really, though Kanye West borrowed some sonic structure ideas from her. More clearly, her success paved the way for countless others to be brave with their own artistic visions and ambitions. – Steve Hochman

38 BJORK

The moment Björk hit the public’s consciousness, it was obvious there was something singular about the pixie-like Icelandic artist. Unselfconscious and bold, whether it was with her former post-punk art rock group The Sugarcubes or her solo work, the 16-time Grammy nominee pushed the boundaries of pop with innovative and eclectic musical ideas.

Incorporating technology with audio and visual elements, her sounds and looks (including the famous Oscars swan outfit) are as forward-facing as they are emotional. Her first solo album, 1993’s Debut, is so flawless and well-rounded in every way: songwriting, production, performance, aesthetic, that I wish it were my album. Debut is in no way a one-off — 1995’s Post repeated its brilliance without repeating any of its ideas. The song “Isobel” spun in my head for months and still plays in my mind when Björk’s name comes up. 1997’s Homogenic marked the trifecta for Björk as she closed out the ‘90s on an all-time high.

She sparked new levels of creativity in her production partners, among them Nellee Hooper, 808 State’s Graham Massey, Tricky and Howie B. She reinvented herself as an artist with each of her 10 studio albums. – Lily Moayeri

37 FELA

“We don’t play world-beat music,” a bare-chested Fela Aníkúlápó Kuti declared sternly on stage at L.A.’s Greek Theatre during a 1990 concert. “We play African music.” Fela, as he’s known around the globe, was ever-defiant, never one to compromise. The only concessions he made to the non-African markets may have been to keep his extended, hard-jazz-funk jams — James Brown/Miles Davis grooves repatriated to the Mother Continent — down to 30 minutes or so, rather than all night as he and his bands would often do at his club, The Shrine, in his hometown of Lagos, Nigeria.

Going between keyboards and sax and singing/chanting in Nigerian Pidgin English, he gave his fierce, pointed takes of political and cultural fury, often with a mocking tone, never afraid to run afoul of the military government that ruled his nation for many years of his life, his albums carrying such titles as “Why Black Man Dey Suffer,” “Expensive Shit” and “Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense.”

That latter, 1986 release featured the half-hour “Look and Laugh,” a relentless, menacing account of the attack by Nigerian soldiers on his compound, which he’d declared an independent state, in which his mother was killed, he was injured and his home and property burned. After his death in 1997 his legend only grew, a legacy carried by his musical sons Femi and Seun, in Bill Jones’ vivid Broadway hit Fela! and in countless young bands around the world. But the musical power and presence, the cultural and political fire? The overwhelming spectacle of his performances with his sprawling band — including some of his 27 wives, or “Queens,” dancing and singing? No one can match Fela. – Steve Hochman

36 NILE RODGERS

Nile’s parents were Greenwich Village beatniks who were friends with the Beat poets, jazz musicians and other intellectuals, and introduced their son to music. Which sparked one of the greatest musical imaginations, careers and outputs of recording history.

Superficially most known for his revelatory funk band Chic, co-founded with Bernard Edwards, and their epic disco era hit “Le Freak”, Nile has steadily released new albums (and a fair number of movie soundtracks) and experimented gloriously with new sounds and styles over the last 40 years. But he’s also on this list for having the best ears in music — he’s the ultimate producer who has produced records for dozens of musicians, ranging from David Bowie, Mick Jagger, Madonna, Duran Duran, Peter Gabriel, Daft Punk, The Thompson Twins and Grace Jones (and, ahem, Michael Bolton). Pedants amongst you will point out that the Madonna and Gabriel records came out in 1984, to which I say, psshaw! You’re still listening to them now, aren’t you? – Bob Guccione, Jr

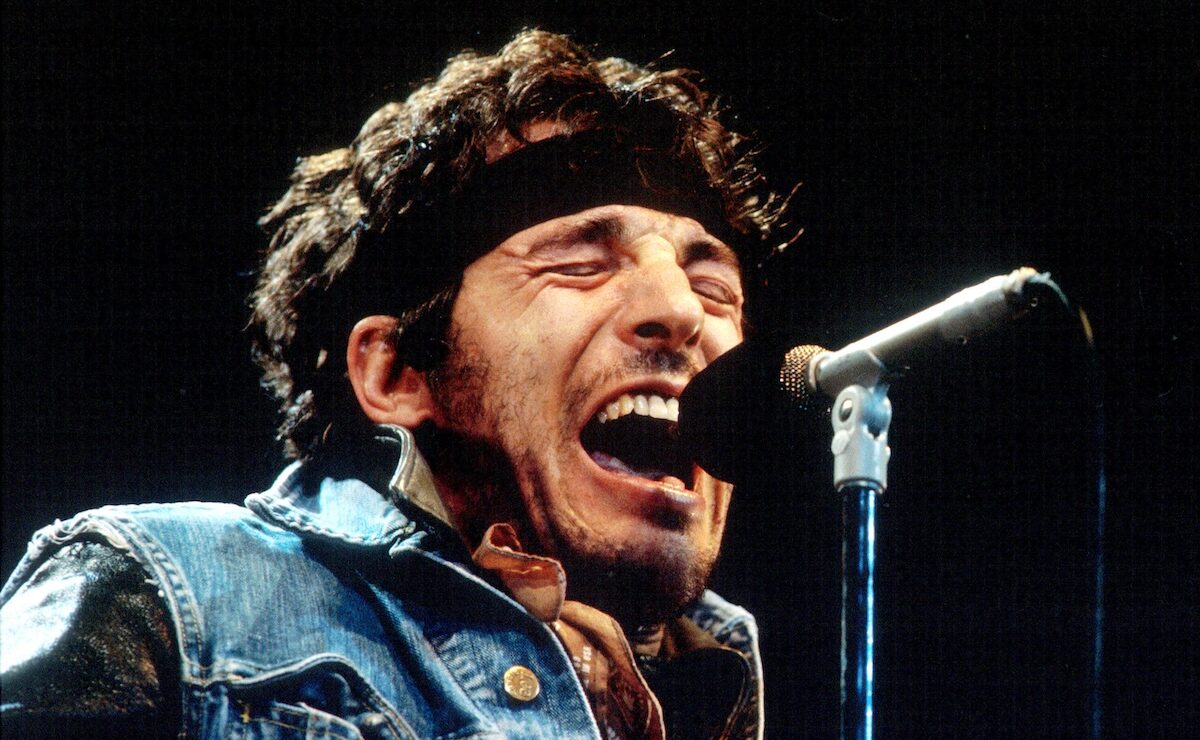

35 BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN

Bruce Springsteen began the last 40 years the same way that he’s ending them: by being the most explosive live rock-and-roll performer ever to strap on a Telecaster. In 1986, when he unleashed the three-disc/five-LP/three-cassette box Live/1975-1986, such packages were rare events, so besides being a literal big deal, it was a cultural big deal as well, eventually going platinum 13 times. What has he been doing recently? Touring almost non-stop and making recordings of the shows, plus plenty of archival concerts, available via nugs.net or his own dot-net site. Clearly, he wants to put an unbridgeable chasm between himself and whoever rock ‘n roll’s second most explosive live performer is. He’s succeeding.

20 of the 31 songs on his latest setlist come from between 1973 and 1984, signalling that in terms of new material, his last four decades have been spotty. Still, no one responded more insightfully to a disintegrating marriage than he did in 1987 with Tunnel of Love (his last to be issued as an eight-track!) or more robustly to the 9/11 attacks than with The Rising. – Arsenio Orteza

34 THE REPLACEMENTS

Between the “Never mind” of Never Mind the Bollocks and Nirvana’s Nevermind, there was the song that kicked off side two of Pleased to Meet Me, the last great Replacements album: “Never Mind.” If one attitude could be said to unite punk, grunge, and the music that linked the two, “Never Mind” would be it. And it’s hardly surprising that all three bands imploded just as stardom swung within reach.

Some will argue that Paul Westerberg, Chris Mars, and the half-brothers Bob and Tommy Stinson can’t be among the greats of the last 40 years because their undisputed masterpiece, Let It Be, came out 41 years ago. OK. It did. But it came out late in ’84, and on Twin/Tone, an indie label with limited PR. So it didn’t come to a lot of people’s attention until 1985. And although the two Sire albums that followed, Tim (’86) and Pleased to Meet Me (’87), have their naysayers, they also contain some of the group’s — and the era’s — most enduring and definitive songs.

About those: Westerberg’s gift was the ability to combine snottiness and pathos until you couldn’t tell where one ended and the other began. The Replacements’ gift as musicians was the ability to do something similar with sound. Often combustible, chaotic, and sloppy, they inevitably ended up careening around irresistible melodies that at their core distilled the essence of the guilty-pleasure pop that the group loved to get drunk enough to cover (badly) onstage. At such times, they became the Everyband that not enough people — the Replacements themselves included — knew that they needed. – Arsenio Orteza

33 CHRIS WHITELY

Chris Whitley is an outlier on this list, but he’s not a novelty item meant to make you shake your head and go “wow, I guess music critics know so much more than we do!” (true though that is, of course). He never had a real hit – a couple of his songs broke the Top 40, peaking in the lower regions of it. He released about a dozen records in his short lifetime and none of them were big commercial hits. But he was a magnificent musician, the musician’s musician whose avid devotees range from Springsteen, Keith Richards and Iggy Pop to Mellencamp, Tom Petty, Alanis Morissette and John Mayer. And they really do know more than any of us.

Whitley was a blues rock player and singer-songwriter. He had that soul. His song “Big Sky Country” is indisputably one of the great songs recorded in the past 70 years, let alone the last 40. He wasn’t a video star or a radio star, and he didn’t really break any sonic ceilings. He died too young. The general consensus is he was underappreciated. Not here he’s not. – Bob Guccione, Jr

32 RUN-D.M.C.

Run-D.M.C emerged from Hollis, Queens, in 1983, just as hip-hop’s first generation, from the South Bronx and Harlem, was losing steam. Run (Joseph Simmons), D.M.C (Darryl McDaniels) and Jam Master Jay (Jason Mizell), three friends who loved the larger-than-life characters of comic books, were the start of the music’s second generation, the New School: suburban, collegiate, with a chip on their shoulder, declaring themselves to be louder and tougher and deffer. Where the Old School updated R&B grooves and fashions, Run-D.M.C consciously broke from the past, rhyming over a beat box or a rock guitar, dressing like guys from the neighborhood.

True to form, they introduced themselves with a battle track, “Sucker M.C.’s,” challenging all comers: “You’re a five-dollar boy and I’m a million-dollar man/You’re a sucker M.C. and you’re my fan.”

They broke barriers for hip hop: MTV, the cover of SPIN and Rolling Stone, first gold hip-hop album, first multi-platinum, a collaboration with Aerosmith on “Walk This Way” that was both their apogee and their albatross. Chuck D of Public Enemy called them the “Beatles of hip hop” — the act that came along after Chuck Berry and Little Richard and reconceived what the music and the industry could be.

Also true to form, after the music moved again, starting circa 1990, they imploded their own way. Run became the Rev. Run; D.M.C. battled alcoholism and depression; and Jay was murdered in his studio in 2002 over a drug deal. As for the hip-hop revolutions that succeeded them, none would exist had it not been for the Kings from Queens. – John Leland

31 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST

Q-Tip, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, Phife Dawg and Jarobi — collectively A Tribe Called Quest — were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2024, one of only a handful of hip-hop acts to be so recognized. The moment was painfully bittersweet without Phife, who died in March 2016, months before the Queens-bred group released their sixth and final album, We Got It from Here…Thank You 4 Your Service. The project capped a colorful catalog that effortlessly embodies hip-hop culture at its root. Beginning with 1990’s People’s Instinctive Travels and The Paths of Rhythm, Tribe released a series of seminal albums that transformed the genre with their jazz-infused beats and socially conscious lyrics, including 1991’s The Low End Theory and 1993’s Midnight Marauders. As members of the Native Tongues collective, Tribe was an Afrocentric antidote to the gangsta rap dominating the West Coast and they influenced countless artists along the way. – Kyle Eustice

30 KHALED

The first time I heard Khaled I heard Cheb Khaled, the young version (because Cheb means young in Arabic). It was in Paris in the late ’80s and my good friend Jean-François Bizot, editor of the great French pop culture magazine Actuel, gave me a hand recorded cassette and said, in the usual dismissive voice he had for me when he introduced me to something he felt I should have known about years before, “this is raï, you have to know about this, and Cheb Khaled is the best of them all.” And he certainly was.

I use the past tense only to refer to the literally mind-altering sound that exploded from my cassette player when I was back in New York. Raï is percussive, fast, gorgeous, moving music even though, to me, the lyrics are incomprehensible. It’s sexy music, again in a literal sense, not a thin descriptive way. And it is truly rebellious music — in Islam-strict Algeria — perhaps a hair moreso when Khaled started than now, but still you wouldn’t want to step far out of line there — this was the one (and I do mean one) sanctioned artistic dissent, an almost mythic music of songs of sex and political complaint. Imagine the very sexual, socially controversial rap music in the ’80s in America, if the government could put to death any musician it felt like, but chose, arbitrarily, not to. That was raï for most of the last forty or so years. (In the mid ’90s, irritated by the emboldened defiance the music had taken on, the government did kill one of the main proponents, Cheb Hasni, and started cracking down on other raï stars, who went into exile, if they weren’t already there, like Khaled.)

Khaled’s first officially released record, Kutché, a collaboration with compatriot jazz player Safy Boutella, was superb and is a great place to start listening to him. Khaled is extraordinary and has the worldwide hit — seriously — “Didi” on it. Don Was produced that album, which piqued some interest in the west. Sahra is, to the cognoscenti, his classic.

Khaled has gone on to become the highest seller of raï records of all time, having sold over 80 million copies. – Bob Guccione, Jr.

29 AMY WINEHOUSE

Wandering an old citadel with Serbian friends one blazing summer afternoon in Belgrade, I hear a godawful mewling coming from a stage set up in parkland below. “What the hell’s that?” I ask.

“Amy Winehouse,” says Ana. “She do soundcheck for concert tonight. But she don’t need check. I can tell her now: is shit.”

The next morning we hear that the show was indeed a disaster, with Winehouse too trashed to do much more than stumble about, drop her mic, forget her songs, and mumble, while the crowd jeered and booed.

Her tour was then cancelled, and four weeks and a couple days later Amy joined the 27 Club, a pair of empty vodka bottles on the floor beside her north London death bed.

But unlike others in the 27 pantheon — Jimbo, Jimi, Janis — Winehouse, with just two studio albums, wasn’t very productive. Even Nirvana did three LPs before Kurt joined the club.

Nevertheless, as brief, unproductive, and messed up as her time was, Amy Winehouse beguiled millions with her Betty Boop trainwreck siren panache, her rebel jazz queen stage command, her devil-may-care humor (going to rehab? “No, no, no!”) , and with being anachronistic enough to actually fucking sing.

And that voice: sensually, sexually, vehemently flecked with risk — spiced with scars, with knowing that life is in the burning. – Matt Thompson

28 BUDDY GUY

At 88, the polka-dotted guitarist, whose infectious spirit matches his signature blues virtuosity, is one of the last living links to the blues’ trip from the rural South (he was born and raised in tiny Lettsworth, Louisiana) to the urban North (he moved to Chicago in 1957), where the music was electrified and urbanized and, soon enough, globalized in its powerful grasp on young musicians everywhere.

His crucial collaboration was with blues harpist-singer Junior Wells (who died in 1998). 1965’s Hoodoo Man Blues, billed to Junior Wells’ Chicago Blues Band, launched them from sidemen to stars, proponents of the raw South Side sound. Guy’s playing here, crisp and nimble, was like no one else’s, and the album is still cited as one of blues’ most influential.

He remains influential. His Buddy Guy’s Legends club in Chicago is a mecca for musicians and fans alike since 1989, and he’s mentored generations of young players, Christone “Kingfish” Ingram among the latest. He’s earned eight Grammys (plus a Lifetime Achievement nod), a National Medal of Arts in 2003 and Kennedy Center Honors in 2012. And he’s still on the road, six decades after Chicago blues entrepreneur Leonard Chess dismissed Guy’s playing as “just making noise.” – Steve Hochman

27 CESÁRIA ÉVORA

Cesária was born in Cape Verde, in the middle of the ocean between Africa and Brazil, on August 27, 1941, in Mindelo, a wild port city on São Vincente, one of the islands that make up this former slave trade way station. She grew up with a genetic connection to music, her father was a violinist who died while she was still young, but mostly absorbed the morna music of the islands, swirling around her and from the ground into her misshapen feet. She played in the port bars as a teenager, had some success in Europe in the ’50s and had retired from music by the ’70s, since she couldn’t support her kids, and her three husbands weren’t around for long. She went back to living with her mother.

That would have been the end of the story for most people. But Cesária had the entirety of her success starting in 1985, when the seed of her having a track on a woman’s anthology led to her being discovered, brought to Paris, the real melting pot of music, American pretensions aside, and the beginning of a trajectory that made her one of the most famous and successful African musicians of all time.

She sang with the transcendent depth and melancholy of Édith Piaf and Billie Holiday. She sang sad songs with joy, in the sweet patois of Cape Verdean Creole, a mash of Portuguese, Brazilian and African influences. Her songs “Sodade” and “Partida” seduced the world without being what we’d recognize as Billboard hits. The ’90s were her most productive years, in which she released 6 of the 11 albums she recorded in her lifetime, including Cesaria Evora in ’95 and Cabo Verde in ’97, both immortal recordings. When she died in 2011 of health issues from drinking and smoking, she was little known in America but revered around the world as one of the greatest singers of all time.

She was known as “The Queen of Morna”, and “The Barefoot Diva” for performing barefoot, a tradition following once taking her shoes off in the middle of a show because her feet hurt. A woman of the sea, she once said, wistfully, “The sea sings a song, but we don’t understand it.” – Bob Guccione, Jr.

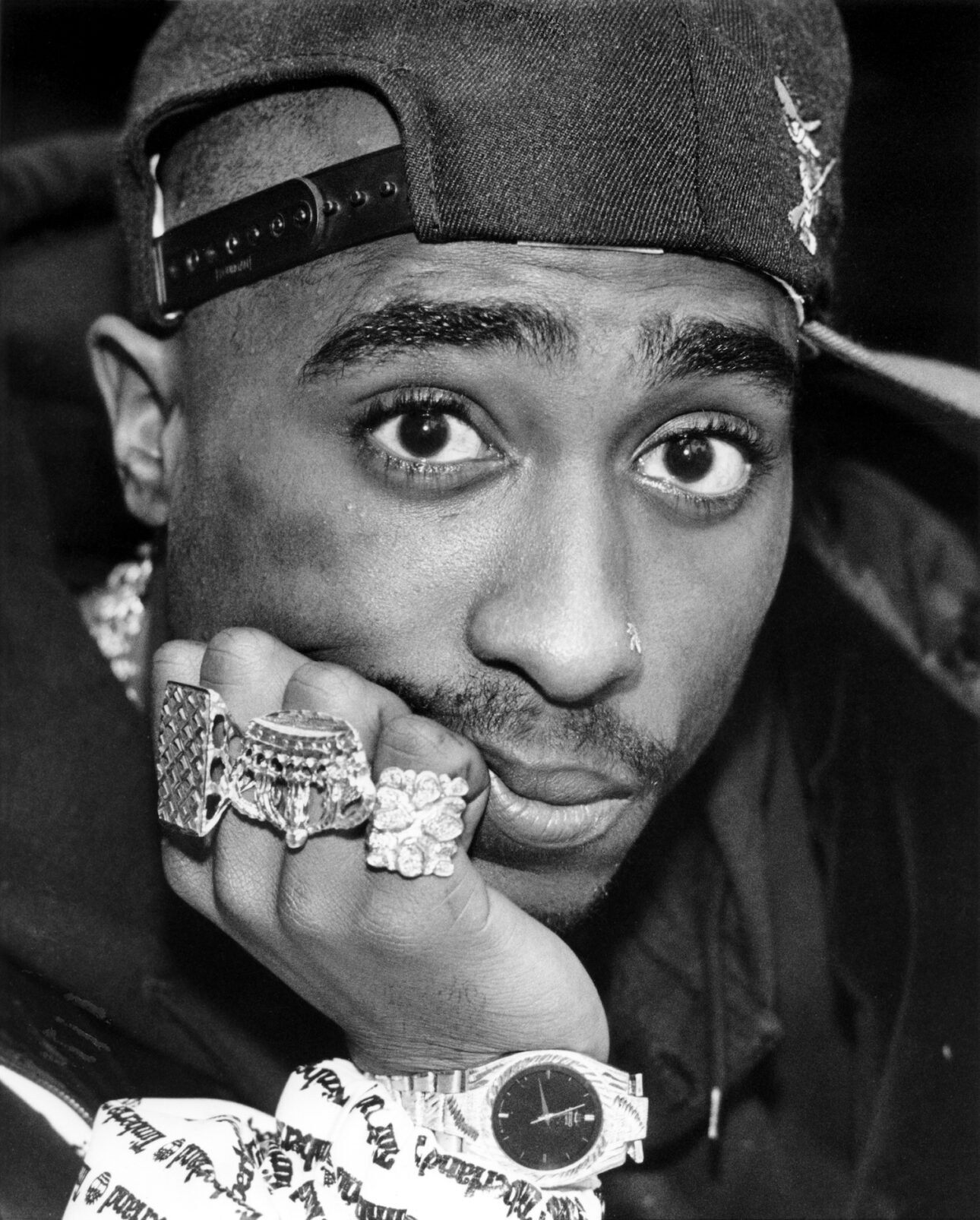

26 2PAC

Tupac Shakur managed to make a seismic impact on hip-hop culture in the 25 short years he was on earth. With his gruff, authoritative voice, he delivered an intoxicating mix of gangsta rap and poetry with an air of rebelliousness that captivated millions. From the painfully blunt realism of “Dear Mama,” which dove into his early life with a drug-addicted mother, to the lyrical brutality of his Biggie diss track, “Hit ‘Em Up,” Shakur was able to express a vast range of emotions atypical of a ’90s rapper.

Simultaneously, the charismatic East Harlem native was an activist, using songs like the Grammy-nominated “Changes” to bring awareness to the plight of Black people: “Cops give a damn about a negro/Pull the trigger, kill a n—, he’s a hero/Give the crack to the kids, who the hell cares?/One less hungry mouth on the welfare.” With each scathing word, Shakur painted a perfect portrait of his reality while using his signature bravado to get people to listen — and they’re still listening. Nearly 30 years after his murder, Shakur’s music remains timeless and continues to give a voice to marginalized communities around the globe. – Kyle Eustice

Metallica have done more than anybody else on this list to get themselves laughed right off this list. There’s the Napster bullshit, which proved suing your own fans is a bad look. There’s Some Kind of Monster. There’s the deeply stupid drum sound on St. Anger. There’s every note on Lulu. But! There’s also “The Unforgiven.” And “One.” And every note of “Master of Puppets.”

The good definitively outweighs all the bad. In the 1980s they defined thrash — galloping tempos, furious soloing, fussy kickdrums, dark theatricality — and soldiered on even after the death of bassist Cliff Burton. Quite possibly the heaviest band to have a number-one album, they brought their massive attack into the mainstream just as the Satanic Panic was fizzling out. No longer underdogs by the 1990s, they faltered in the glare of the spotlight, but their late-career albums, especially 2016’s Hardwired… to Self-Destruct, have earned them enough good will to thrive in the 2020s. – Steve Deusner

24 TAYLOR SWIFT

The biggest pop star in the world was only 16 years old when she released her debut single back in 2006. It was a heart-on-sleeve country ballad called “Tim McGraw,” in which she romanticized a summer fling and hoped her ex would think of her whenever he heard that other singer. Her country origins may be Taylor’s most overlooked era — she has played “Tim McGraw” only once in the last decade — but that genre’s emphasis on songwriting and storytelling have informed every lyric she’s ever penned.

She traffics in romantic totems, the small little reminders we keep even after a relationship ends: a favorite song, a scarf, a mixtape, the memory of a kiss in the rain. Intimacy remains precious even after that lover has left your life, even when you’ve moved on to someone new. It’s a powerful idea, so generous in spirit that it makes Taylor’s anti-hero self-deprecation (“It’s me. Hi, I’m the problem”) sound insincere, and it’s made her a hero to several generations of fans who hear their own experiences and aspirations in her songs. Those legions of Swifties have sustained her through various mishaps — the undercooked reputation, the overstuffed Tortured Poets Department — and have made the last 20 years one long imperial phase. – Steve Deusner

23 SALIF KEITA

There are no shortage of musicians claiming to be the King or Queen of this or that, but the only one (on this list at least) who is actual royalty is Salif Keita, a member of Mali’s royal family. That actually doesn’t mean much these days, even in Mali, but, paradoxically, Salif is much more tangibly music royalty. He created a sound loosely referred to as Afropop, blending the rhythms of mande, a traditional form of music and storytelling from West Africa, other African musical influences, and elements of jazz and R&B.

But I don’t know if he can be characterized so simply or so loosely. First of all, he has a voice like no other musician I’ve ever heard — a falsetto and a range that defies gravity. His singing can lull you into a dreamlike state, or grab you by the throat and terrify you.

His songs evoke a time-unbroken and rhythm-uninterrupted Africa (and not just on his most famous track, “Africa”). Listen to him soar on “Mandjou”, the haunting, trilling “Nyanyama”, and the sensual “Yamore” (with Cesária Évora, also on this list). They are alternatively fresh, quaintly dated, and ancient. And spellbinding. – Bob Guccione, Jr.

22 TRENT REZNOR / NIN

Trent Reznor has an annoying, whiney voice, is no star at any of the instruments he plays, and stages performances more akin to plastic-hair-era-DEVO-on-ADHD-meds than a real rawk band. His hair, when long and lank, is irritating, and when he gets a buzzcut and wears muscle shirts it’s somehow all even worse. Nerdy Reznor has been a self-programming bot at least as far back as 1989 and the bouncy aggro pop of Nine Inch Nails’ debut album, Pretty Hate Machine. For the onetime leader of the “industrial [rock] movement,” as SPIN crowned him and NIN in 1992, he ain’t no Al Jourgensen, whose chemically engineered multi-drummer Ministry then absolutely wiped the floor with Reznor.

But, Reznor is a fucking inspiration for showing that none of the above matters when one’s will and vision are honed so diamond hard that a creative force can become way way way way more than the sum of its parts. That’s how Reznor pushed through from the contrived highs of Pretty Hate Machine to the true extremes of 1992’s Broken and 1994’s Downward Spiral, as well as a wealth of evocative ambient music, and how through the 1990s and beyond this profoundly driven nerd on the tools became a refitter and creative resuscitator for lost old stars including David Bowie and Gary Numan.

And then there’s the Reznor who, with Atticus Ross, made movie scores matter again. From the swelling, intrusive schmaltz of conventional movie music, we suddenly had the psycho-physiological precision of tracks like “In Motion,” integral as it is to David Fincher’s The Social Network.

Reznor has limits, but he is a conduit for forces which don’t. – Matt Thompson

21 NUSRAT FATEH ALI KHAN

A nondescript events hall at the LAX Hilton seems an unlikely spot for history to happen, but one evening in 1990, when Pakistani Qawwali singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan performed to benefit the building of a cancer hospital in Lahore, it did. With an audience mostly of fellow Pakistanis and a handful of local guests, Nusrat sat cross-legged on stage, on the threshold of global fame. His fantastic flights of melismatic vocals, from serene to frenzied, and the reedy harmoniums and burbling percussion of his so-called “Party” ensemble, drew ecstatic cheers from his compatriots, and blew the minds of the others.

The world embraced Khan and his Sufi devotional music. Western audiences flocked to concerts. Other musicians flocked too: Eddie Vedder collaborated with him for the Dead Man Walking soundtrack. Peter Gabriel included Nusrat on the title track of Passion. Rick Rubin wanted to team him with Johnny Cash (if only that had happened!). Gabriel further opened the door, releasing tradition-rooted Shahen-Shah in 1988 on his Real World label, and then Mustt Mustt two years later, both world music landmarks.

Nusrat died way too young in 2003, at age 48. There are hundreds of his recordings available — official releases, live bootlegs, remix projects both authorized and not. Shahen-Shah remains the best introduction. – Steve Hochman

20 VAN MORRISON

The immortal Irish singer is a rare Irish Knight of the British realm, and a real one, because he was born in Northern Ireland, not a fake one like Bob Geldof, who was born in non-British Ireland.

He started making records in, what, 1920? The 1800s? Anyway, long, long ago. But remarkably his best albums — except for his bestest-best, Astral Weeks, which may be the greatest album ever recorded — are post 1985.

The quixotically titled, glorious No Guru, No Method, No Teacher which came out in ’86, the transcendent Poetic Champions Compose in ’87 and the extraordinary, elegiac double-album Hymns to the Silence (’91) are three of the most beautiful recordings ever produced. Other masterpieces include Too Long in Exile, Days Like This, The Prophet Speaks and his most recent, this summer’s Remembering Now.

Morrison’s singing is more textured and moving than anyone else’s, and more evocative and stronger than anyone else’s. It has the mournful joy of the Irish, a particular, layered sound, pickpocketed from angels. The only Irish voice to come close — sit down, Bono — was Sinead, but I think even she would have yielded to Van.

Other than in Ireland, he’s never had a number one album. Sometimes he didn’t enter the charts at all. He never seemed to care and I don’t either. – Bob Guccione, Jr.

19 TRACY CHAPMAN

“Fast Car” was the perfect song for its moment. The debut from this Cleveland singer-songwriter served as a vivid rebuke of seven years of disastrously callous Reaganism, speaking quiet truth to power and somehow peaking in the U.S. top 10. Treating the personal as political and vice versa, she projected an unshakeable belief in folk music’s ability to address class, race, and gender, which means that “Fast Car” has survived Nice & Smooth sampling it hilariously and Luke Combs covering it clumsily to become a true American standard. It’s right up there with “Born to Run” and “Blowin’ In the Wind” as pop’s most potent wishes for freedom. But Chapman’s catalog is deeper than that one song. Her debut and her underrated 1989 follow-up, Crossroads, speak of revolution in clear, hushed terms, as though passing secret messages throughout the underground. And in 1995, right at the peak of alternative rock, Chapman scored another unlikely hit with “Give Me One Reason”, which may be the last 12-bar blues to ever break the top 5. Chapman hasn’t released new music in nearly 20 years, but her songs are sturdy enough — revolutionary enough — to sound perfect for any moment. – Stephen Deusner

18 DAVID BOWIE

Few had a run like David Bowie’s from 1970 to 1980. His 12 studio albums through those years are jammed with genius and Bowie stood astride the era, an androgyne colossus.

But then the gods withdrew their favor, and that singular heat in him tapered off as he broke through to commercial superstardom, with 1983’s Let’s Dance selling millions of copies.

And this is where he starts to earn his place on this list, for the post-’85 Bowie was no longer a dazzling young dude surfing the ’70s zeitgeist with polymorphous perversity. In 1987, Bowie turned 40 and released his 17th studio album, Never Let Me Down — with an air of us needing to know that Bowie was still relevant.

But David kept experimenting, and maturing, with Reeves Gabrels adding grippingly spasmodic guitar on songs like “The Heart’s Filthy Lesson”, used on David Fincher’s Se7en. This was the era of Bowie’s fertile camaraderie with Trent Reznor, who unleashed the potential of 1997’s “I’m Afraid of Americans”, cowritten by Bowie and Eno.

More great moments came but none as great as the manner and music of his vanishing. On his 69th birthday, January 8, 2016, two days before dying, Bowie proved he didn’t need the gods’ favor, youth, drugs, or anything other than an absolute, final, purity of vision when he released Black Star. Harrowing, astonishing songs such as “Lazarus” and the title track eclipse even young Bowie. – Matt Thompson

17 KILLER MIKE

How many artists have won three rap Grammys then gotten arrested minutes later, for an altercation with a security guard? Only one, and he’s special — Michael Render, a.k.a. Killer Mike.

Ironically, Killer Mike is one of the good guys. He won those Grammys in 2024 for Best Rap Song and Best Performance for “Scientists & Engineers” and Best Album (Michael). Not bad for someone whose music is more slow burn than Big Bang. And then there’s his duo with El-P, Run the Jewels, whose fourth album, RTJ4, dropped shortly after George Floyd did, becoming a BLM soundtrack. And before all that, there was his involvement with Outkast at the beginning of the millennium, which introduced him to the public.

Mike seldom leans into the predictable. His Netflix series Trigger Warning with Killer Mike found him undertaking one creative black-community social experiment after another (living for three days using only black-owned products, helping the Crips and Bloods mint their own sodas). He’s active socio-politically too, canvassing for Bernie Sanders, opening black-neighborhood-anchoring barbershops, and co-founding a bank to fight financial redlining. But he’s no cookie-cutter Socialist. To him, constitutional gun ownership is as much a civil right as the right to vote. – Kasson Bratton and Justin Sarachik

16 PETER GABRIEL

Ever since co-founding Genesis with schoolmates Tony Banks, Mike Rutherford, Anthony Phillips and Chris Stewart in 1967, Peter Gabriel has had a flair for the dramatic, and treating performance as theater, and playing in elaborate costumes, including an intricate fox head and his wife’s red dress for a show Dublin, used on the album cover of 1972’s Foxtrot.

Astonishingly, because he was then and has always been ahead of his time, this led to his exit in 1975, reportedly because Gabriel’s on-stage antics distracted from the rest of the band. But he continued evolving in his solo career, being an early visionary in music videos, with groundbreaking hits “Sledgehammer”, “Red Rain”, and “Big Time”, all from his 1986 album, So, and 1992’s “Digging in the Dirt”, which won a Best Music Video Grammy Award for its surrealism.

Whether he blended rock with world-music elements, as in “In Your Eyes” featuring African drummers and Youssou N’Dour on vocals, or eulogizing anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko in “Biko”, or writing songs about poverty in America, as in his collaboration with Kate Bush on “Don’t Give Up”, and even “Father, Son”, a song he wrote as an ode to his elderly father for OVO, Gabriel consistently plunged the depth of human emotion, musically and lyrically. He may have also invented stage diving, but that’s up for debate. – Charles Moss

15 DEPECHE MODE

Clangs and crashes, nipples and leather, a frontman who looks like a schoolboy but belts in a deep baritone — Depeche Mode emerged with contradictions in full view. They lit the fuse for danceable electronic music and synth-pop gold, sharpening it with the jagged edge of alternative rock. Never have the inner workings of a synthesizer felt so sensitive, so dark, so painfully human. It’s their singular fusion of man and machine — electronics pulsing with emotion — that makes Depeche Mode one of the most enduring bands of the last (almost) half century.

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductees and multiple Grammy nominees, they’ve built a body of work both consistent and undeniable, with 100 million records sold and counting. Their audience regenerates with each era, drawn in by timeless themes of desire, faith, addiction, and alienation. They speak to parts of ourselves we usually keep quiet. Still innovating, still expanding their reach through commanding live shows, Depeche Mode’s influence runs deep. Their legacy is not just longevity — it’s resonance, decade after decade. – Lily Moayeri

14 RADIOHEAD

Imagine if Bruce Springsteen’s first hit had been a novelty dance tune, and he still went on to become the Boss. Maybe, then, you can grasp how big, and unlikely, it is that Radiohead — formed in 1985 at an Oxfordshire boys school by friends Thom Yorke, brothers Colin and Jonny Greenwood, Ed O’Brien and Philip Selway — managed not just to escape being a one-hit wonder with the post-plaid snark of “Creep”, but go on to be one of the most dynamic, fiercely creative and hugely popular forces in contemporary music of the last several decades.

If 1997’s dark-wave OK Computer redefined Radiohead, then 2000’s madhouse-rave Kid A redefined what a rock band could be. Thom Yorke ever on the edge of tears. Jonny Greenwood ever on the edge of frontiers. And since those two landmark albums, Radiohead have only expanded their quest, combining existential hide-and-seek with the majestic spiritual, seek-and-find of Olivier Messiaen. Seriously, is there another band that could have brought a 20th century French chromesthesiac composer into the conversation of 21st century rock? And headlined major festivals while doing it?

Side projects have been no less bracing for the range of their explorations, from jazzy-prog with the Smile (Yorke, Jonny Greenwood and drummer Tom Skinner) to Greenwood’s movie scores (There Will Be Blood, Phantom Thread), classical works and brilliant collaborations Junun (with Israeli composer Shy Ben Tzur and Indian musicians) and Jarak Qaribak (songs from around the Middle East with Israeli rock star Dudu Tassa). As for the group, Radiohead’s most recent album, 2016’s A Moon Shaped Pool, is arguably its most emotional and mature — still powered by the restless, seeking spirit of its youth. Now that’s novel. – Steve Hochman

13 JOHN MELLENCAMP

The songs your supermarket won’t let die are his early pop hits, like “Jack and Diane” and “Pink Houses”, when he was still struggling to get out of the Johnny Cougar straightjacket, but he hit what turned out to be his lasting stride, and lifelong alliance with the common man, with 1985’s Scarecrow. Its thumping title track “Rain on the Scarecrow”, and seminal cinema verite video, was a proclamation of the systematic pillaging of the American farmer (ha! Sound familiar, 2025?). By 1987’s The Lonesome Jubilee he had established his mid-western, rural Indiana, Appalachian instruments-accented sound, and he was his own genre. And the Cougar yoke was gone.

In the late ’80s and ’90s he released a string of superb albums that were commercial hits but also uncompromising social challenges. He championed the underdog and called out the bastards. Steadily for the last 30 years he has continued to put out soulful, achingly beautiful music, perhaps cresting with 2023 Orpheus Descending, with its powerful tracks “Hey God” and “The Eyes of Portland”.

While so many musicians were content to have singalong records, Mellencamp inured himself as the rural poet laureate. As a songwriter he’s Springsteen and Dylan’s equal, and if you don’t think so, just ask them, they’ll tell you. – Bob Guccione, Jr.

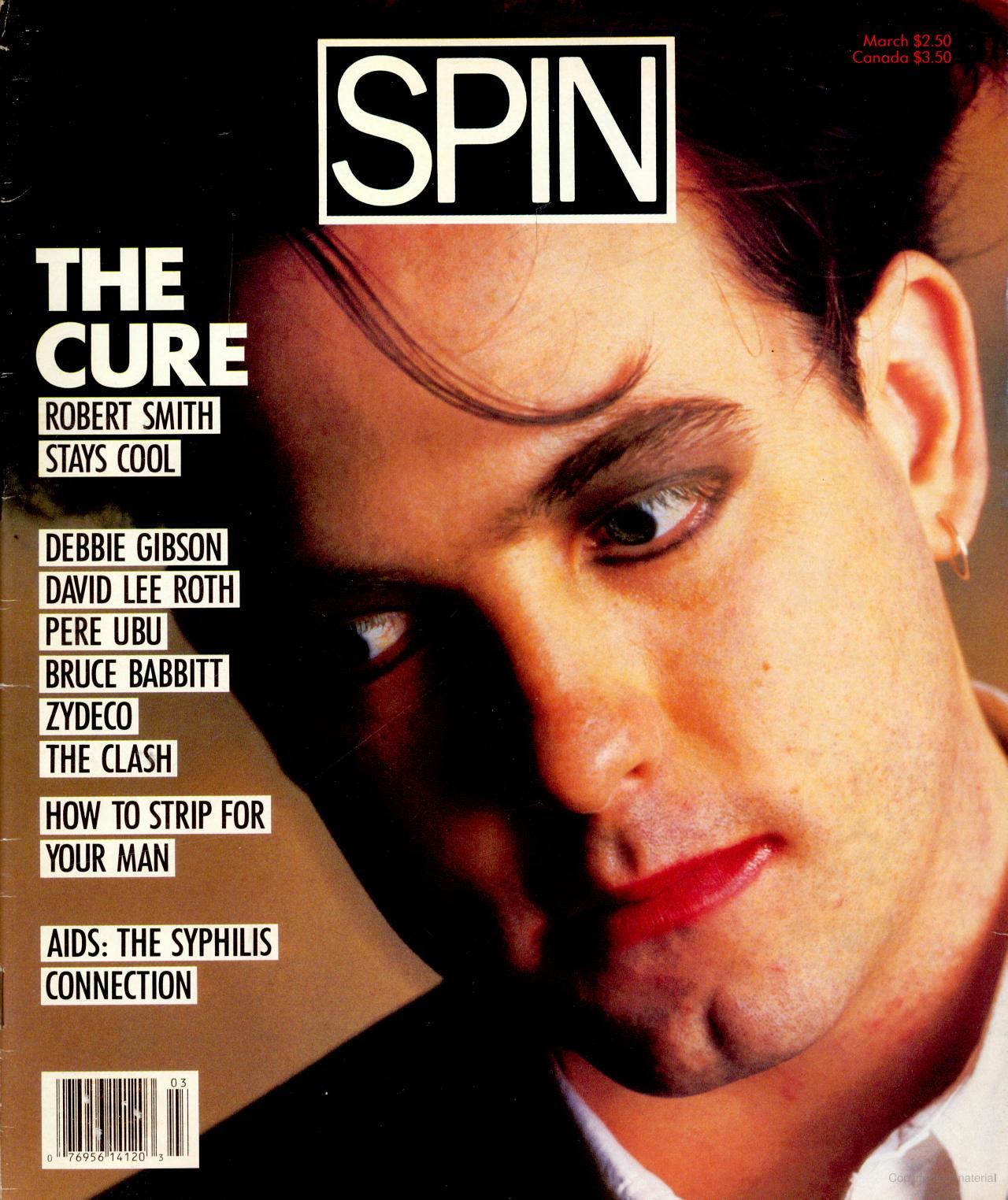

12 THE CURE

What started as a school band in 1970s England went on to leave an undeniable impact on global music and culture. The Cure’s gothic rock sound is that dreamlike combination of flanger guitar, synthesizers, and drum and bass exchange, with experiments in new wave, alternative rock, and even dance pop. Anthems like “Just Like Heaven”, “Boys Don’t Cry”, and “Friday I’m in Love” and the band’s eighth studio album, Disintegration (1989), widely considered their masterpiece, featuring tracks including “Lovesong” and “Pictures of You”, cement them in the pantheon.

Their dark aesthetic and frontman Robert Smith’s wild look, with his trademark untamed hair and black eye-makeup, shaped a global community of goth culture, and even film characters.

After 16 years without releasing new music, the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame-inducted group is back on its original record label, Fiction Records, and put out the critically acclaimed Songs Of A Lost World in 2024.

Despite genre experimentation and a revolving door of members, The Cure was always true to its core, hooking fans in for nearly 50 years with a legacy of introspection and vulnerability, which maybe we could all use more of these days. – Sofia Goldstein

11 OASIS

The Gallagher brothers’ reunion — after a long and heavily publicized estrangement — has made them inescapable, much like when they first appeared on the global stage three decades ago. The music, visceral (if derivative), landed with earth-shaking force due to its sheer energy. But it was the constant, unfiltered banter, especially from Noel Gallagher — although brother Liam more than pulled his weight in that department — which kept Oasis in the spotlight. The public were hooked, even if you sometimes wondered, is the draw the music or the mythology?

Their live shows were, and are again, spectacular and all that’s great about rock ‘n roll. Their catalog, if we’re being honest, doesn’t offer much beyond the first two albums: Definitely Maybe, (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, and the B-sides collection The Masterplan. But that material is formidable and epoch defining. Their greatest hits albums lean heavily on that early period, and their current setlists rarely wander far from it. But the staying power of those few records continues to fuel the phenomenon. – Lily Moayeri

10 PEARL JAM

The stupidest debate in music, stupider than the Beatles vs. the Stones, or East Coast vs. West Coast, was the trumped-up grunge grudge match of Nirvana vs. Pearl Jam. As if there was only room for one at the top of Mopey Mountain.

Sure, now it seems silly. But back then it was serious. That PJ never got pulled into that publicly is testimony to their spirit and sense of purpose. That they didn’t get pulled into the vacuum after Cobain’s death is miraculous.

Their debut album Ten, with its poetic, sturdily rocking hits — the howl-for-meaning “Alive,” the trauma-riddled “Jeremy” and the glorious, elegiac “Even Flow” — is a powerful disaffection-generation complement to Nevermind. Their fierce stand against Ticketmaster was a we’re-on-your-side, community-galvanizing statement. A defining image of their graciousness is Eddie Vedder, sorrow on his face, placing his hand on his heart at the end of the 1994 SNL show the group played, days after Kurt killed himself.

31 years later, those characteristics remain at the, well, heart of PJ, who have evolved into adults carrying responsibilities accumulated — kids, fame, mortality — with a commitment that powers their music. Listen to the fiery rock of 2024’s Dark Matter, or Vedder’s solo albums and their expansive, exuberant expressions of humanity and hope.

Pearl Jam is an enduringly, brilliantly shining star. – Steve Hochman

9 EMINEM

When Marshall Mathers exploded right around the time Y2K was threatening to annihilate society, he boasted not one but two hip-hop alter egos: The Detroit native rapped both as Eminem (ego) and as Slim Shady (id), often within the same verse, which along with his impossibly intricate flow suggested an infinite regression of selves all devised to hate hard on Marshall Mathers. He joked about murder, rape, torture, violence, and techno, and we gave him a pass because he obviously hated himself more than anyone or anything else. That’s the whole point of 8 Mile, and it means ‘funny’ tracks like “My Name Is” and dark tracks still possess a vivid queasiness this deep into the next century. Untangling those belligerent selves made him the greatest rapper alive, at least for a few years, but after he finally separated those warring selves, circa The Eminem Show, he could barely hold our attention. It was, in retrospect, impossible for one man to sustain that level of self-disgust, but the mantle has been taken up by every incel, edgelord, and troll defined by their own sense of disenfranchisement but unable to see the world beyond their own wifi. Marshall Mathers might have won the battle, but Slim Shady is winning the war. – Stephen Deusner

8 OUTKAST

At the intersection of Conrad Avenue and Lakewood Terrace in Atlanta’s historic Lakewood Heights neighborhood sits a modest brick home with white awnings and black shutters. There’s no indication that the dingy basement, with red dirt floors and torn out bucket seats from a car was once the makeshift studio The Dungeon, where Organized Noize producers Rico Wade, Ray Murray and Sleepy Brown crafted the demos for Outkast’s 1994 debut, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik.

The talented trio worked tirelessly on beats for André “André 3000” Benjamin and Antwan “Big Boi” Patton, teenaged rap prodigies who met two years prior at the Lenox Square shopping mall. Their single “Player’s Ball”, landed them a deal with LaFace Records. It put Southern hip-hop on the map.

Outkast went on to release ATLiens in 1996 and Aquemini in 1998, two albums that highlighted their experimental and unconventional approach to hip-hop, with Big Boi’s hard-hitting street anthems and 3 Stacks providing the balance with his often esoteric raps. Coupled with live instrumentation and 1970s funk, Southern soul, gospel, country and psychedelic rock-inspired beats, Outkast was (and remains) one of one.

In November, Outkast will be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Though it’s unlikely they’ll ever reconvene as Outkast (their last tour was in 2014), the Grammy Award-winning duo made their mark, proving unequivocally that the South always had something to say. – Kyle Eustice

7 DAVE GROHL / FOO FIGHTERS

Like everyone else I wore out Nevermind and romanticized the Nirvana saga. And when I saw them play Australia’s Gold Coast in ’92 they seemed bleary and were outplayed by their support act, the Violent Femmes. Even so, I went a little bananas when Nirvana followed up that juggernaut not with a slide into the comfortable but instead with songs as harrowing and visceral as “Heart-Shaped Box” and “Rape Me”. These guys have guts, I felt. Then what happened happened. And here’s where drummer Dave Grohl showed serious guts.

After some months of post-catastrophe withdrawal in 1994, Grohl got back to work, playing whatever instrument he had to in order to bang out in a mere six days what would be released the next year as the Foo Fighter’s debut, self-titled album. And it rocks. It took a long time to stop pointlessly comparing it to that other band he survived and simply let it flow, but flow it does. Its wind-in-the-hair rock might have bugged Nirvana purists but maybe, just maybe, death trips aren’t so… sustainable.

And nothing seems as here-to-stay, as bankable, as solid, as a guitar-strapping Dave Grohl on his great ride with the Foos and an array of side gigs from Queens of the Stone Age to Tenacious D. Over the Foos’ 11 studio albums, Grohl and co. have produced a litany of instant classics and earned a stellar reputation as live performers. No half-assed, bleary efforts here. This is turning it on. Bigtime. Every time. – Matt Thompson

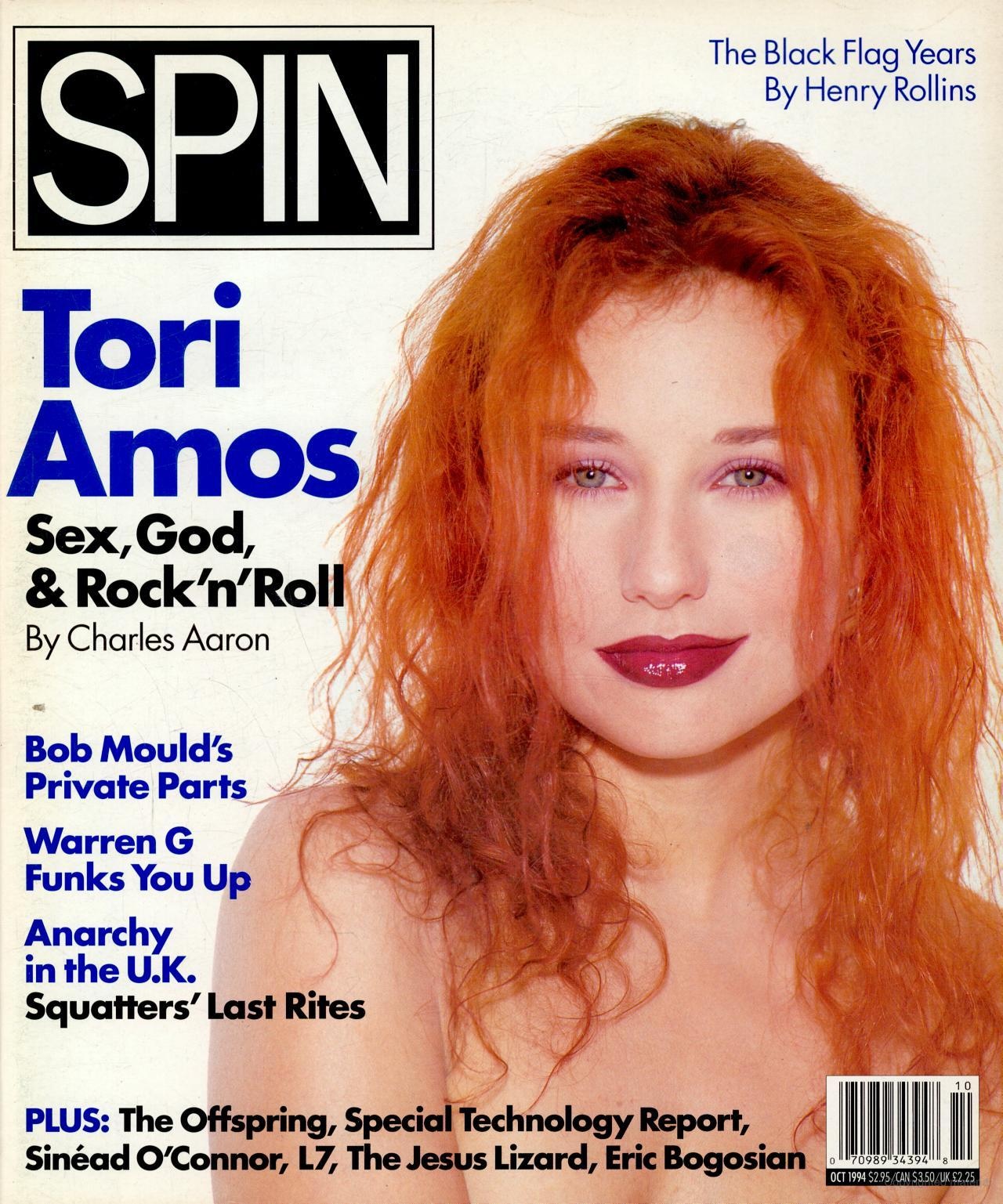

6 TORI AMOS

When Tori Amos released Little Earthquakes in early 1992, there were a lot of guys singing about guy things (and grunge, Nirvana’s Nevermind was released in late 1991). So, what were the odds of this fiery virtuoso — with her strikingly beautiful mezzo-soprano voice, singing openly and unapologetically about the depths of the female experience — shaking up the industry? At a time when music had such little space for women, she parted our consciousness and offered a new perspective and new voice.

And this is what Tori has done throughout her entire career: She shines a light on tough topics, and honors all parts of our humanity as a storyteller of mythic proportions, mesmerizing us with her unflinching bravery (combined with some fucking incredible songwriting). She’s still breaking ground and inspiring others to be true to themselves. With that, her message and model has created a following rightfully evangelistic. I cannot think of a more kick-ass church. – Liza Lentini

5 PRINCE

Prince’s famous three-minute, unrehearsed guitar solo on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” during the 2004 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ceremony sums him up. A last-minute addition to an all-star tribute to George Harrison, Prince played one of the greatest riffs in modern rock history on his H.S. Anderson Mad Cat guitar, wearing an impeccably-stylish black suit with a bright red, high-collared dress shirt and matching fedora. He was showing off, of course, but my God, what a show.

Since dying at the age of 58 in 2016, Prince has taken on mythical status. He is one of the best-selling recording stars of all time, won too many awards to list here, who played a mesmerizing 27 different instruments on his 1978 debut, For You. While 1984’s Purple Rain might be his crowning achievement, legend has it that he challenged himself to write a new song every day, resulting in an astounding 39 albums released during his lifetime.

Nobody took music, or the music business, more seriously than Prince; a staunch believer in artists’ rights who fought to maintain creative control over his songs. He was a master performer, songwriter, composer, and producer, and cultivated a flamboyant, androgynous persona that oozed sex. He had five No. 1 singles and wrote Sinead O’Connor’s only No. 1 hit, “Nothing Compares 2 U”, and the Bangles’ “Manic Monday”, which only made it to No. 2 because his immortal “Kiss” was top of the charts. – Charles Moss

4 MADONNA

She changed the world. Bruce Springsteen may have been the biggest rock star in the ’80s (may still be) but Madonna was the biggest star. No movie star, director, painter, writer or other musician created the tsunamic wake she did when she floated into and out of a country. Crowds the size of those who came to see the Pope greeted her when she arrived in a city like Rome, besieging her hotel. (When she later played Evita in a movie, that role was a step down from the adulation she witnessed in real life.)

Her music was great (I think, always did) but that alone didn’t create the rip in the cultural space-time continuum. She was a liberator. She was 100 percent who she wanted to be and who she said she was, which was more than refreshing, it was, then, society-tearing down. Love her or hate her, she was (I believe) equally happy with either reaction. She freed sex from the prissy cotton wool Reagan’s America was wrapping it back in. Nothing she did was as outrageous as the next thing she did. She was a sustained cultural orgasm.

She coincided with MTV’s rise perfectly, and defined them as much as they helped define her. Her videos were small movies — some R-rated level and banned — and they were great! Her songs and videos were controversial on multiple levels, including the tremendous furor that “Like a Prayer” caused for using Christian crosses and kissing the statue of a Black saint. She sold more than 300 million records, but that’s beside the point. Madonna more embodied the spirit of rock ‘n roll than rock stars. She was nobody’s fool, and still isn’t. – Bob Guccione, Jr

3 SINÉAD O’CONNOR (SHUHADA’ SADAQAT)

When I interviewed Sinéad in October of 2020, she was honest, trusting, candid, friendly, vulnerable, and so incredibly funny. During our talk, she reiterated what she’d said to many other journalists: that her “controversial” October ’92 SNL performance (when she ripped up the Pope’s picture) didn’t derail her career, it put her back on track as a singer. She told me that while personally she had some regrets, professionally she had none.

Sinéad released 10 studio albums before she passed away at 56 in 2023, and they were all powerful and beautiful and tingled your spine. She was unwavering in her fearlessness and her activism, and taught us what it means to stand your ground even when your oppressors are loud and plenty. When I wrote about her before she died people routinely jeered and bullied her. After she died, to the same people, she was suddenly “right about everything.”

What would our world be if we had more Sinéad O’Connors? Try not to dim their light. We need these brave, big-hearted rebels now more than ever. – Liza Lentini

2 PUBLIC ENEMY

The first time Def Jam co-founder Russell Simmons heard a Public Enemy demo, he tossed it out of Rick Rubin’s dorm window at NYU. At least that’s how Doctor Dre remembers it. The world perhaps wasn’t ready for what Public Enemy offered — the cold, hard truth about the rampant racism America was built on. But Rubin was intrigued and ultimately Def Jam signed them.

Chuck D formed PE with Flavor Flav while working at Long Island’s Adelphi University radio station, WBAU, where they had a hip-hop show. To promote it, they made a demo called “Public Enemy Number One”, under the name Chuck D and Spectrum City — the single Simmons threw out a window.

Instead of the party-style rhyming of Sugarhill Gang and Kurtis Blow, Chuck D proselytized about racial injustice, police brutality, economic inequality, and media bias. Backed by Flav, The Bomb Squad, and Public Enemy’s security, the S1Ws, Chuck turned rap on its head and influenced countless others.

From 1987’s Yo! Bum Rush the Show and 1988’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back to 1990’s Fear of a Black Planet and 1991’s Apocalypse 91… The Enemy Strikes Black, PE was more than the “Black CNN” moniker Chuck coined. They became a movement. “Fight the Power”, “Don’t Believe the Hype” and “Can’t Truss It” defined the era and were rallying cries.

Their artifacts are in The Smithsonian and they’re in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Their lyrics are studied in college. “Rap music and hip-hop at its best does the right thing,” Chuck D once said. “So yes, maybe there goes the musical neighborhood, but… here comes the truth.” – Kyle Eustice

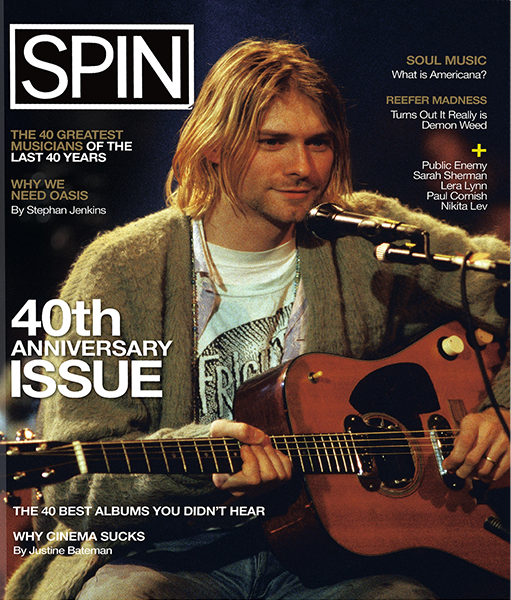

1 KURT COBAIN / NIRVANA

It was never the music, or just the music, that made Nirvana special. The band and its frontman were always, to my mind, more interesting for what they said and did on stage or in interviews or wrote in their liner notes than for their music. Sure, Kurt managed to sprinkle enough Beatles on his grunge flakes to make the music palatable, even occasionally sublime, but Nirvana was always better as a live experience, and even then peaked early — better suited to the intimate rooms of its nascence than the arenas of its adolescence.

The mayhem Nirvana could inflict on a 250-capacity club circa Bleach was genuinely exhilarating. When Dave Grohl joined as drummer their musicianship upgraded, technically, but because they became famous so quickly after that, there was almost no way for such a raucous and undisciplined band to sound good in the cavernous spaces they then had to play. Kurt stopped enjoying the experience, and started faking his periodic outbursts of manic energy — throwing himself into the drums became his version of Pete Townshend smashing his guitar.

And then there was the heroin, which… didn’t help.

But Nirvana as a musical entity long ago disconnected itself from the weight of rock mythology that has accreted since Kurt killed himself over 30 years ago. He had already become larger than life during his life; he’s now morphed into a symbol, a cipher, a face on a t-shirt that means whatever you want it to mean to whoever wears it. People still listen to the music, of course, but not as many as listen to, for example, Taylor Swift or Drake. That doesn’t mean anything in terms of its importance. Millions of people listened to Kenny G and Guns ‘N’ Roses and Michael Bolton and even — this one is hard to believe — Smashing Pumpkins when Nirvana was putting out records.

That wasn’t really the point, then or now: Nirvana’s ascension represented — or we thought it did at the time — the breakthrough of the kind of music people at SPIN had championed for years, and that people before SPIN had championed for years before that, as far back at least as the Velvet Underground. Whether it was called underground rock, punk rock, college rock, indie rock, modern rock, alternative rock, or my favorite, rock rock, it had always sat in the shadow of — and often in opposition to — pop culture. There were exceptions, like R.E.M. or I guess U2, but those exceptions had always been accompanied by a measure of compromise. Nirvana’s success, on its own terms, represented the coming out party of the shadow-dwellers, and it’s hard to explain to the youngs how exciting that time was for those of us invested in the idea of Nirvana as the vanguard of a whole new era of Actually Good Music reaching a wide audience. To be clear, it was not that, and we were wrong. But that’s what it felt like at the time.

I have a vivid memory, which may be false, I can’t find it on YouTube, of Eddie Money coming out of the MTV Awards or the Grammys or some awards show where Nirvana played complaining that musicians “these days” didn’t know how to play. That was the point, Mr. Money. Ever since God invented the Stooges, instrumental mastery proved no impediment to effulgent self-expression. Anybody can do this was the animating idea of punk rock. Not anybody can do this was the reality, but that’s a music lesson for another day. It wasn’t just music, either — exciting things were happening in the world of independent movies, with Slacker, Sex Lies and Videotape, and Do the Right Thing, among many others, concurrently blowing away the bloated excesses of corporate ’80s franchise action pics. Forever. Yeah. That was wrong, too. We thought the culture was shifting, and maybe it was, for a minute, until it was bought and co-opted and superseded by shinier, prettier — and this is the important part — more pliant brands of popular success.

In retrospect, it was unrealistic to believe that Nirvana was anything but a fluke, a meteor, a moonshot. Their own record company initially shipped a little over 45,000 copies of Nevermind to record stores, hoping to sell maybe 250,000 by the end of its run, which sounds like a lot, now, but was not back then. It went on to sell over 30 million copies world-wide. That part you know. You also know that its very much unexpected success pushed Kurt, already suffering from severe depression, increasingly reliant on heroin, into a slough of despond from which he could not, and maybe did not want to, extricate himself. There’s nothing glamorous or mythic or cool about a junkie who kills himself, but circumstances have conspired to turn Kurt into a thing he hated then and would hate even more now. Maybe he would have come to terms with it, had he lived. But he didn’t live.

In the end Nirvana’s success did not augur anything but itself, but their music still has the power to evoke that brief break in the mercilessly mercantile clouds of popular culture. It’s not enough, given the cost, but it’s what we have. Let’s celebrate that. It’ll never happen again. – James Greer

→ Continue reading at Spin