Before Madonna vogued, before RuPaul was a household name, before Beyoncé built a Renaissance, there were queens carving out space in a city that had none for them.

Ballroom culture was alive and pulsing through New York’s underground clubs, basements, and warehouses long before drag hit reality TV. And no, we’re not talking about classical square dancing. To the queer community, ballroom is a subculture built on freedom, according to CR Fashion book. Freedom from social norms, from oppression, and from invisibility.

Ballroom culture represents a large social ecosystem built around competitive events known as balls. Drag is one part of ballroom, but it also includes voguing, runway walking, modeling, and a wide range of categories judged on everything from fashion to charisma to “realness.”

Drag is an art form, designed by the LGBTQ+, where performers use clothing, makeup, and attitude to embody a gender, persona, or character. These often exaggerate femininity or masculinity to challenge norms, express identity, and entertain. Drag shows can range from intimate lip-sync performances in bars to large-scale balls with lively performances and hundreds of fans cheering. But for many it’s not just performance. It’s survival, resistance, and brilliance in the face of a world that refused to see queer people, especially those of color.

Early History

The roots of ballroom culture reach back to the vibrant social scenes of Harlem, long before the phenomenon was brought into mainstream awareness through shows like Pose and features in magazines such as Vogue and The New Yorker. The Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and ’30s laid the groundwork, nurturing Black artistic and cultural expression in a segregated America. One of the earliest and most influential venues was the Hamilton Lodge 710, located on West 142nd Street in Harlem. It became a landmark in the community for hosting regular balls that drew Black and Latin performers and spectators, helping to formalize the competitive and creative traditions that would define ballroom culture for decades.

The post-war decades allowed the ballroom scene to begin to take shape as we know it today. Drag balls were underground events where participants competed for trophies, respect, and fame. By the late 1960s, as the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement began to gain momentum, following events like the Stonewall Riots, Black and Latin queer communities were often excluded from mainstream gay and lesbian spaces. In response, they expanded the ballroom scene, creating Houses and events where they could find acceptance, mentorship, and community.

In the late 1960s, Black drag queens Crystal and Lottie LaBeija established the House of LaBeija in Harlem, the first formal House in modern ballroom culture. They began hosting balls of their own, due to racism in the LGBTQ+ community at the time. Drag queen, Paris Dupree, often called the “Mother of the Ballroom,” helped formalize the House system. These kinship networks functioned like families, offering emotional support, mentorship, and shelter for LGBTQ+ youth rejected by their biological families.

These Houses became the backbone of the ballroom scene, providing both structure and fierce competition. Categories are imaginative and wide-ranging, each a unique challenge testing style, skill, and creativity. Some focus on appearance, like beauty, fashion, and sex; others test performance skills, such as voguing, runway, or acting. “Realness,” for example, is a category where performers convincingly embody their persona’s gender according to societal ideals, and judges vote on who they believe would “pass” most successfully as a man or woman in the current world. These competitions serve not only as entertainment but also as a way for marginalized Black and Latin LGBTQ+ people to assert identity, claim visibility, and survive in a society that often excludes them.

Defining Moments

The 1980s and 1990s marked a turning point for ballroom culture as it moved from scattered events to an organized, intensely competitive scene built around “Houses,” often led by a “Mother” or “Father.” Houses like LaBeija, Xtravaganza, and the legendary House of Ninja became names synonymous with excellence and creativity. The scene grew out of Harlem, with its rich Black cultural history, and spread into Manhattan and Brooklyn, where vibrant queer communities provided space to perform, compete, and build chosen families.

The late 20th-century era also birthed voguing, a dance style inspired by the poses of fashion models but has since evolved into so much more. The original form of voguing consisted of sharp posing with an influence from Vogue Magazine and Egyptian hieroglyphics. Fading into the 90s, fluid movements emerged with more complex and new ways of impressing the judges. In modern forms like, “vogue fem”, performers reflect deeper stories with movements blending jazz, modern dance, ballet, and hip-hop. Drag performers use precise hand and arm techniques, and a mix of fast, angular, or slower, sensual motions to outshine the competition. Iconic moves that leaked from the community include the duck walk and the dip. Willi Ninja, known as the Godfather of Voguing, was central to voguing’s early evolution, calling it a form of critique and resistance on the ballroom floor.

The soundtrack to this movement is equally unique for the purpose of creating an original sound for the emerging community. Ballroom music grew from house, electronic, and disco influences, with modern sounds now incorporating hip-hop, funk, and R&B. However Ballroom music’s signature sound comes from the “Ha-crash” which is a percussive hit on the fourth beat, signaling dancers to strike a pose.

Mainstream Ballroom

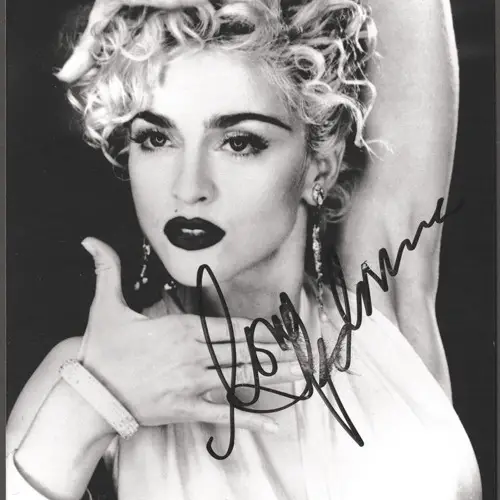

When Madonna released her hit single “Vogue” in 1990, she brought elements of ballroom culture to global audiences, lifting voguing straight from Harlem and into the spotlight. For many, it was the first time they saw the dance form. Ballroom icons like José and Luis Xtravaganza appeared in her videos and on tour.

That same year, Jennie Livingston’s documentary “Paris Is Burning” opened a rare window into the world of ballroom, highlighting the lives of legends like Pepper LaBeija, Dorian Corey, and Angie Xtravaganza, and capturing the grit, glamour, and heartbreak of the scene. The film also sparked controversy, as many questioned whether the filmmaker had profited from the struggles of queer and trans people of color without fully giving back to the community she portrayed. Then came RuPaul with “Supermodel (You Better Work)” in 1992. RuPaul brought drag into living rooms via MTV, becoming the most visible drag queen in the world. Additionally, his show, RuPaul’s Drag Race introduced ballroom terms like “shade,” “reading,” and “realness” to a wider audience, as many of these words had been in ballroom parlance for decades. Following that was the popular HBO original Legendary in 2020.

This wave of visibility was complicated. On one hand, it helped queer culture break into the mainstream. On the other hand, it often erases the Black and Latin roots of Ballroom, flattening a subculture built on survival into catchphrases and fashion trends.

Yet the influence of Ballroom remains strong, the fashion, language, and attitude, all shaped pop culture in ways many people do not realize. While mainstream audiences were catching up, Ballroom continued on its own terms, spreading from Harlem. Its legacy is rooted in New York’s streets and stages and continues to shape pop culture today.

Ballroom Today

Ballroom has never disappeared, it has evolved. In today’s New York City, its energy pulses through queer music and nightlife.

People like Mike Q, Liv Lux Miyake-Mugler, Yasha LaBeija, Leggoh JohVera, and more have carried the legacy forward with moves and sounds that are unapologetically queer and unmistakably New York. Their music and drag channel the ballroom spirit: fierce, freedom, style, and resilience.

Today’s performers do not find themselves confined to any one genre or aesthetic. Like the founders of Ballroom they mix and remix, pulling from variety to build energy that reflects the complexity of identity. Houses remain vital as chosen families and creative collectives, offering mentorship, competing at balls, and creating platforms for new artists and dancers. Houses like LaBeija and Xtravaganza still hold influence, while newer groups such as Mizrahi, Lanvin, West, Gorgeous Gucci, and more push Ballroom into the future.

Living in Legacy

In New York, Ballroom has been many things. A protest. A party. A lifeline. From Harlem ballrooms to Brooklyn warehouses to your phone screen, the culture has always found a way to keep moving, even when no one was watching. Clubs and venues across New York City, including House of Yes and Webster Hall, continue to welcome this art and community.

Ballroom culture still moves today in the beat of a house track, in a perfect runway walk in a screaming crowd; Ballroom isn’t just about being seen, it’s about making sure nobody looks away. Born from exclusion within marginalized groups, Ballroom built a home for anyone who doesn’t fit the labels society demands.

Just like Ballroom, New York City is always celebrating, dancing, and evolving. You can keep up with it in our NYC Metro section.

→ Continue reading at NYS Music