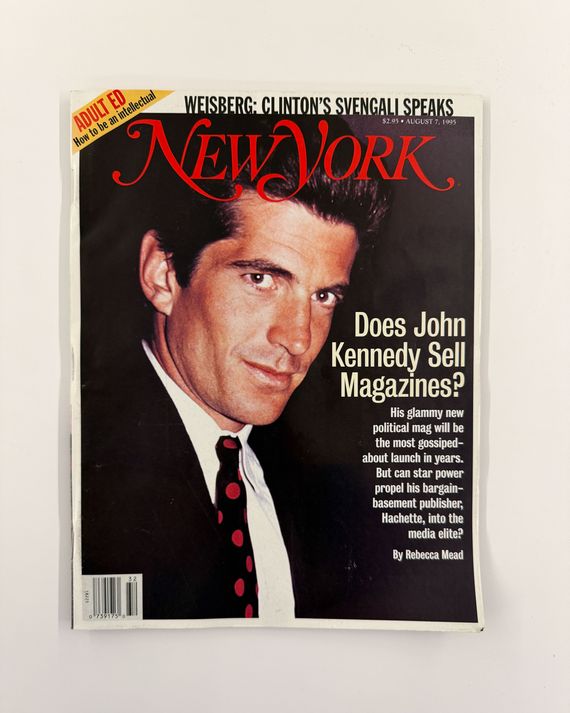

Photo: New York Magazine

Editor’s note: This story first appeared in New York’s issue of August 7, 1995. We’re republishing it to coincide with the release of FX’s television series Love Story: John F. Kennedy Jr. and Carolyn Bessette.

You’re in the Oyster Bar at Grand Central, listening to Michael Berman — the co-founder and executive publisher of George, a soon-to-debut glossy commonly referred to as “John Kennedy’s magazine” by almost everyone except Michael Berman — trying to compensate for the fact that he is not John Kennedy.

Berman, who is perfectly decent-looking and can doubtless Rollerblade as well as the next man, but who would probably not qualify as America’s most eligible bachelor even if he were still unmarried, relates the magazine’s mission in the practiced tones of a salesman — one of his hats at George, where he’s been doing the rounds of potential advertisers. The magazine, he says, is intended to be to politics what Rolling Stone is to popular music, or Forbes is to business, or Allure is to beauty: a fan of its industry. Instead of writing about the politicians you’ve already heard of, it is going to be telling you about the people behind the scenes: the speechwriters, the ad-makers, the fund-raisers, the fixers. Unlike existing political magazines, it’s got no particular political allegiance. Instead, it’s got snazzy graphics. It’s got Herb Ritts.

Eventually, Berman gets around to the fact that George has also got John F. Kennedy Jr., which helps when it comes to starting up a magazine about politics. Kennedy’s ability to get political types on the phone is probably surpassed only by that of the president, and his ability to get almost anyone else on the phone is probably unrivaled. But while Kennedy has access, he also has what you might call recess: Though he can get anyone to talk to him, he doesn’t have to talk to anyone, and especially not to you.

This is an issue that raises its indelicate head somewhere in the second half of your conversation in the Oyster Bar, and one that Berman addresses in the practiced tones of a stooge — presumably another of his hats, perhaps dating as far back as when he and Kennedy were undergraduates together at Brown. Kennedy, Berman explains, “is an editor-in-chief; he’s an entrepreneur; and he is going to do whatever he can do to ensure the success of the magazine, short of compromising his own sense of self. And that is why I am talking to you and he’s not, because John doesn’t give interviews.”

Berman’s apologetic, terribly nice about it. “Part of this is that we kind of view ourselves as co-founders here, and one of us speaks for the other,” he says. “And in this case, I am speaking for him. And it’s not nearly as enticing. Sorry.”

And then you reflect upon George’s dedication to covering the people behind the scenes in politics, the nameless folk doing good things in the background, and you have the following, not very generous-spirited, thought: George is going to be about the Michael Bermans of politics. And you think, Well, a good journalist ought to be able to make that interesting.

_

George, which will be appearing in vast quantities on newsstands in September, does, in fact, promise to be far more interesting than implied by Berman’s pitch — in which he tried to be helpful while giving nothing away, which tends to make for blandness. Not only does George have the Kennedy draw (the man himself will be doing a Q&A every issue with one of those people who return his phone calls — he reportedly interviewed George Wallace for the first issue), but it’s also got Eric Etheridge, the well-regarded former executive editor of the New York Observer, serving as Kennedy’s No. 2; and some smart writers on good subjects, for instance, in the first issue, Mim Udovitch on Newt Gingrich’s gay, pudding-basin-coiffed sister.

But to people concerned with the politics of publishing, just as interesting as George itself are the activities of the magazine’s publisher, Hachette Filipacchi Magazines, which apparently has been gripped by a raging appetite for acquiring publications. Hachette, a subsidiary of the huge French weapons-communications conglomerate the Lagardare Group, has in the five months since it struck the George deal (it’s a partnership with Kennedy and Berman’s Random Ventures) purchased Family Life from Wenner Media, Video from Reefe Communications, Inc.; Mirabella from Rupert Murdoch’s News America; and Premiere from K-III Communications (which owns New York). This month, it was announced that Hachette would be providing publishing services to David Lauren’s young-person magazine, Swing, with a view to buying into the magazine, which hitherto has been with Hearst, next year.

All of which has brought Hachette — which already owns 22 magazines ranging from Elle to Metropolitan Home to Woman’s Day to Boating to Car and Driver to Road & Track — a significantly raised profile in the magazine business. Hachette has long been what you might call the Michael Berman of the publishing industry: Unlike its flashy, celebrified counterparts Condé Nast and Hearst, Hachette has always been rather in the background, working behind the scenes, getting on with its business.

Hachette president David Pecker.

Photo: New York Magazine

A relatively young presence in America — Elle, launched in 1985 in partnership with Rupert Murdoch, was Hachette’s first publication — the magazine group swelled in size when in 1988 it bought the former CBS Magazines from Peter Diamandis. That purchase resulted in an odd French-glamour–American-trade hybrid, which was Hachette’s defining flavor until now, if anyone cared to look, which no one much did. These days, the identity Hachette would like to project is one of entrepreneurial energy — running a lean, no-nonsense, financially pragmatic company with

little time for frills or fancy. Its editors and executives are not boldface sorts, and its president, David Pecker, hardly has the profile of Hearst’s Claeys Bahrenburg or Condé Nast’s Steve Florio.

But what looks lean to one man looks emaciated to another; and in the eyes of some, Hachette has slimmed its magazines to the bone. At Premiere, a magazine that was hardly overstaffed, there were immediate layoffs after the purchase; Mirabella, which has been cut from 12 to six issues a year, is being produced by a skeleton staff and edited by Elle editor Amy Gross in her spare time. Hachette paid very little for Mirabella and for Family Life, which Jann Wenner wanted to get rid of: “Bottom fishing” is how Claeys Bahrenburg has reputedly been describing Hachette’s behavior to his executives at Hearst. Condé Nast’s Steve Florio is loftily skeptical. “I will tell you a joke,” he says. “I walked right up to David after it was announced that he was buying Premiere, and just a few months ago they’d bought Mirabella. We were at a big function at ‘21.’ I said, ‘David, I’ve got a ’52 Buick with no engine in it; are you interested?’ And he looked at me with a big smirk on his face and said, ‘Florio, I’ll buy it.’ “

But for all the mockery from Florio, David Pecker has managed to transform Hachette into a respectable, if bargain-basement, empire. Pecker was quoted last fall as saying that this was going to be a tough year for magazines, but what it now looks like he meant was, This is going to be a tough year for everyone else, and I’m going to clean up. Pecker is very up about Hachette’s expansion: While talking about the start-up of George one afternoon, he makes a verbal slip, calling the new magazine “a living, breathing orgasm” — which doesn’t, in fact, seem too far from his hopes for it. All in all, Mr. Pecker is pretty excited.

‘Do you mind?” says David Pecker, waving the big cigar he’s smoking. Not at all, actually: Pecker with cigar presents an appealing counterpoint to the framed cover of Cigar Aficionado magazine propped up on the credenza behind his desk. That shows a bulky, grinning Ron Perelman, also with cigar — though it is there that the Pecker/Perelman similarities end. In contrast with Perelman, who is bald, Pecker has a drape of wiry hair swept back from his forehead, spilling over his collar. There’s a kind of attempt at surface smoothness — the expensive shirt, the monogrammed cuffs — but Pecker’s overall demeanor is unpolished: His speech is ebullient and demotic, his mustache reckless and bushy. And despite the theatrical cigar, he doesn’t try to pretend that he’s more of a player than he is: Even though he’s got Perelman’s picture up, Pecker freely admits that he didn’t know him personally before reading in the New York Post in March that the Revlon mogul was interested in buying Premiere, after which he called him up to talk deals, partnering up to buy the magazine for more than $20 million.

Five years ago, before the Perelman pinups, David Pecker was the chief financial officer of the former Diamandis Communications magazine group, a job seemingly more appropriate for a follower than for a leader of industry. Peter Diamandis, the flamboyant founding publisher of Self and something of a legend in ’80s publishing, had headed a group of executives (including Pecker) that bought out CBS Magazines in 1987 for $650 million. Within six months, Diamandis turned around and sold the books to Hachette for a tidy $712 million. Diamandis stayed on with the understanding that he and his associates would continue to run the company. By the time their contracts came up in 1990, however, there were considerable rifts between the French and their American employees. Not least, the French didn’t want to back the nostalgia magazine Memories, one of Diamandis’s favored projects; and they wanted to drop Diamandis’s name from the company’s title. In September 1990, Diamandis and two of his top four executives left; Pecker told the three just before the board meeting in which they were to resign that he had decided to stay with Hachette. Within a year, Pecker was named president; he hasn’t spoken with any of his three former partners since the day of their resignation. “David saw an opportunity for him to become the chief of a publishing company, and I gather he took it,” says Arthur Sukel, one of Diamandis’s gang of four. Pecker’s defection was no surprise, says Sukel, who adds that Hachette made him too rich to have hard feelings. “We knew David. We knew his ambitions. We may have been disappointed, but we were not surprised.”

Pecker’s stated ambition is to build a communications company for the 21st century — with a little help from his new friends, like Ron Perelman. Pecker sees the magazines as resources whose brand names can be mined and exploited in other media: Perelman’s New World Communications Group will develop television programming under the Premiere name, for example.

Pecker points to online services and CD-ROMs, even, perhaps, the movies (Hachette underwrote the upcoming Isaac Mizrahi documentary, Unzipped, and Pecker was listed as an executive producer).

He also clearly wants to shake off Hachette’s rather dowdy reputation and build up a prestigious magazine empire to compete with Condé Nast and Hearst. And he wants to do it on the cheap: The Perelman deal is the kind of arrangement Pecker needs, since Hachette has to answer to its bankers and its parent company in France, where the CBS purchases, and the subsequent buyout of Murdoch’s half of Elle for an additional $150 million, were viewed as considerable expenses. Though the acquisition of Premiere — done in large part because the parent company owns all the other international editions of Premiere — was costly, most Hachette buys are at fire-sale prices. “They do it with a lot of discipline,” says Peter Herbst, who became editor of Family Life when Hachette bought it from Wenner. “They don’t spend a lot of money on these publications; they drive hard deals. When they acquire them, they acquire them with very strict plans of what the next two or three years are going to be like, and they apply it with discipline. This is not guys saying: ‘Whoopee, let’s take over a bunch of magazines.’”

Family Life was acquired using an old Hachette technique — a low original payment, and an arrangement with Wenner by which he gets a share in any future profits. Mirabella was merely taken off the hands of Rupert Murdoch. an old friend of Daniel Filipacchi, the Paris-based owner of Hachette Filipacchi Magazines. And while a start-up like George is a more expensive proposition, Kennedy and Berman had already invested a lot or their own money in market testing of the idea before Hachette came onboard.

The acquisitions strategy is also designed to provide opportunities to sell comprehensive packages to advertisers, a constituency equally as important as the magazine’s readers. Five years ago, Pecker formed a corporate sales force that sells space to advertisers out of the usual range for individual magazines: putting the automotive companies who advertise in Car and Driver or Road & Track into, say, Elle or Elle Decor. Pecker says he can’t think of anything he wouldn’t do for an advertiser — adding the obligatory caveat that he wouldn’t have a favorable article written about an advertiser’s product just because the advertiser wanted it. lt’s an obvious point — though favorable mentions do seem somehow to creep in: In Elle’s hundredth issue, a photo story called “100 Objects of Desire” featured pictures of covetable shoes and jewelry and, seemingly shoehorned in, several Tiffany-framed photos of Hachette-advertising automobiles.

Hachette has drawn high-minded condemnation from others in the industry for doing things for advertisers that its rivals, so far, don’t: Most recently, it put an advertising wrap for perfume around subscription copies of Elle Decor; and it has split the covers of magazines like Elle and Metropolitan Home into a gatefold in order to sell the advertising space underneath — something that is routinely done by European magazines but not by other prestige publishers here. “I have seen my own research on split covers,” says Steve Florio. “And the reader always feels compromised. And I think that a lot of other advertisers feel compromised as well.” (“This is different from Condé Nast,” retorts David Pecker. ”I have the final say here. Steve has to go see Si Newhouse. I wonder what the question would be if he was making the decision.”)

Hachette’s ad-friendly attitude rankles some of its own editors too: When a promotional wrap featuring the magazine’s name and an ad for the perfume Joop! was glued over the cover of a recent issue of Elle Decor sent to subscribers, the magazine’s editor, Marian McEvoy, marshaled a stack of letters and e-mail complaining about the ad. “This was not my decision, as I presume you understand,” she says. “If I were to tell you that I approved of something like that, somebody should fire me.” The cover drew immediate condemnation from the American Society of Magazine Editors, which pointed out that its guidelines state that no advertisement will carry the logo of the magazine — a criticism folks at Hachette seem to relish. “Frankly, I couldn’t care less,” says Daniel Filipacchi. “I am not very interested in what they think and what they say. I guess they have to keep busy.”

_

Pecker’s stipulation that Hachette’s magazines be “friendly to the industry” also applies to George, a position Michael Berman reiterates. “On balance, we are not going to have a point of view,” he says. ‘We say we are approaching the subject as a fan, like Premiere: It is not that they endorse every film, or they like every actor or every performance; but on balance, when you look at it at the end of the year, they are a fan of the process.”

The magazine’s only ideology is to be indefatigably nonideological, treating political figures as players, without passing judgment on their virtues or flaws — sort of a Manhattan, inc. of politics. Politicians and political figures have become stars, goes the argument for George; let’s treat them as such. Regular features will include, on the inside back page, a celebrity writing about what he or she would do if elected to the presidency (Roseanne told People that she’d written a piece for the debut issue, though George wouldn’t confirm it). The magazine will not be doing top-line political news; it hopes to be showing up-and-comers rather than already-theres, so that “by the time they do ascend to the national scene, we do know something about them,” says Berman. “When Bill Clinton announced his candidacy, he was unknown by 70-something percent of the American people, and he had been an American governor for 12 years. That’s somewhat inexcusable,” George would have done Clinton “many years ago, when he was a rising star already, and he was doing good things in his state, and he was an interesting guy with an interesting family.”

Berman holds the optimistic view that the more people know about the workings of politics, the more involved and less cynical they will feel. There is a lot of good, and that often goes unexplored because the bad is far more scintillating and interesting,” he says. “What we are uncovering are interesting people doing interesting things for a lot of the right reasons.” George is not going to be in the business of looking too closely at private lives. “John is very sensitive, obviously — he’s got his own life circumstance, which factors into his thought process,” says Berman. “It is not the intention of this magazine to explore the personal sides of people’s lives. We do not want to expose people’s life secrets. It’s a friendly magazine, trying to make the process a little more friendly. We would not have been the people to follow Gary Hart.”

It’s a scruple one can easily understand Kennedy having, but whether it’s a scruple an effective editor can afford to have is another question. What do you do if you are working on what you expect will be a friendly profile of, say, a young governor like Bill Clinton, and you discover that as well as being an interesting guy with an interesting family, he’s got some interesting mistresses and interesting investment deals as well? You don’t have to be a journalistic lowlife to see problems with accepting your subject’s bona fides at face value; nor do you have to have a gutter mentality to think that worthy pieces about folks doing good things don’t make for the most compelling journalism. Which leaves George with the following paradox: While Kennedy’s allure is the magazine’s greatest asset, Kennedy’s high-mindedness may be its biggest drawback.

Nor will there be any exposure of the editor’s private life — anyone expecting George to be John Kennedy Living is going to be disappointed. Even as he becomes an editor — crossing over and joining the ranks of his pursuers — Kennedy seems determined to retain his glamorous quasi privacy, in which he doesn’t talk to the press but nonetheless seems to put himself in places where he’s bound to be photographed. The idea of an editor-in-chief being above talking to the press is faintly ridiculous, though of course when Kennedy does start talking (Hachette is saying that he’ll be

doing interviews when George is launched), he’ll also start spending his cultural capital. Just as Jackie Kennedy’s mystique depended upon her shunning of the press (though she wasn’t averse to being flatteringly photographed either), John’s celebrity value thus far depends on his being an extremely handsome, extremely silent screen for the projection of other people’s fantasies.

It’s fascinating, then, that Kennedy, a scion of an intensely committed political family who has had the vapidity of celebrity thrust upon him, is now intending to inflict the same process upon today’s political players. The argument for George’s nonpartisan, personality-oriented content holds that Americans are interested in the style of politics more than in the substance (in Washington, actually, there’s far more excitement about Rupert Murdoch’s highly ideological new conservative magazine The Standard, also debuting this fall). It’s a very contemporary, rather bloodless stance. The Kennedy family has always been glamorous, but the Kennedys — at least the male ones — have also been political. There’s something a bit chilling about the son of a truly inspiring, highly partisan president putting out a depoliticized political magazine: That JFK Jr. is post-political is a remarkable sign of the times.

Kennedy’s celebrity value will certainly draw readers to the debut issue, which is being given an enormous launch: 500,000 copies on the newsstand, about the same number that Rolling Stone puts out. The strategy has drawn double takes from publishing experts who wonder whether, after the initial Kennedy-inspired curiosity, a magazine of politics can sustain a readership of that size. “Rolling Stone sells 225,000 on the newsstand, and that’s after it has been published for 25 years and everyone knows what it is,” says publishing consultant David Parker. “Unfortunately, it’s hard to believe that there are as many people interested in politics as there are in Bon Jovi’s latest tour. I think a lot of people will be enthusiastic about George at the beginning, but what happens down the line, when readers who are expecting to get Rollerblade photos of John don’t find them?”

There appears, to be, though, tremendous goodwill in the advertising community to the concept and to Kennedy; the first issue will have 169 pages of advertising. Kennedy himself went to Detroit to pitch the magazine, but he hasn’t been making the rounds at the New York agencies. “I think they are being careful, and having him do nothing,” says Debbie Menfi, the media director at Deutsch Inc. who’s placing Tanqueray in George. “It’s a double-edged sword for me that JFK is tied into this, because

I think they have a very strong editorial mission, but it’s just very hard doing business with this publication in the real world because his celebrity status and involvement are making a lot of people want to jump on the bandwagon, so you can’t really deal with them in terms of sales issues,” she says. “Some of the more difficult questions aren’t being asked because the JFK association is making a lot of that go away.” George isn’t, for instance, guaranteeing circulation figures to advertisers: There just seems to be an assumption that the 500,000 launch — with Cindy Crawford reportedly on the cover — will sell through. The size of the launch, and of the magazine, comes as something

of a surprise to Berman and Kennedy, who, having sought the advice of magazine people all over town (more of those must-return phone calls), were repeatedly told to aim small. The original business plan anticipated a starting circulation of 150,000,

increasing to 300,000 in six years. “But when we got to Hachette,”

says Berman, “it was: How can we make it bigger? How can we help you enhance it? Don’t think about 100,000 copies at the end of three years, think of 500,000 first time out.’”

Berman insists that the George that appears on the newsstand in September will not be very different from the original idea he and Kennedy came up with. But in fact there has been some tension between Kennedy and Berman’s idealistic vision of a smallish-scale magazine that would encourage political engagement and Hachette’s more commercial inclinations. According to Jean-Louis Ginibre, Hachette’s editorial director, the magazine has grown from Kennedy and Berman’s initial idea. “I start to develop the concept a little more with John,” says Ginibre, an old Filipacchi hand who’s been in America for 25 years and last year became a citizen, but who still speaks in an idiosyncratic Frenchified English. “The problem is — it’s not a problem — the question is that they didn’t think the magazine would be so successful in terms of advertising. They had no idea that they would have 250 page for the first issue. So that makes a big magazine suddenly — a magazine that requires more work, more text, more photos, and a magazine also that will be a bigger magazine than they envisioned, so we had to reach more people.” Some of Hachette’s attempts at tweaking have not been taken onboard: There was some discussion of the magazine’s name (not surprising, since industry wisdom suggests that the big, useful magazine agencies like Publishers Clearinghouse will be turned off by something as formless as George). Ginibre’s suggestion that the magazine be called Criss-Cross hardly seems inspired, though. While the original business plan anticipated that only 35 to 40 percent of the readership would be female, Ginibre says the magazine had to be rejiggered to appeal to more women, “because of course John-John has a big following among woman reader.” And not just woman readers either. When Kennedy started showing up at Hachette, says Pecker, “people I never saw before all of a sudden showed up around when there was a meeting; I didn’t even know they worked there.” Xeroxes of a Kennedy magazine-cover photo were pinned up on notice boards at other Hachette magazines: At one magazine, the poster was used as a scorecard for Kennedy sightings. When a new Xerox machine was brought to the floor that George shares with Elle Decor, Metropolitan Home, Family Life, and the Hachette custom publishing magazines, including Sony Style, and was placed within 15 feet of Kennedy’s office, every other Xerox machine on the floor miraculously seemed to be broken, requiring young women from other magazines to make frequent, extremely businesslike trips to do a bit of photocopying. Kennedy, who has a reputation at Hachette for being astonishingly nice, seems unfazed by the attention, though George staff members have joked about setting up a popcorn stand by the machine.

And the excitement has spread even to those who are supposed to be above it all, his fellow editors. Marian McEvoy says she’s never featured Kennedy in her magazine, “though I’m not saying I won’t. Everybody wants to know how John Kennedy lives, don’t they? If somebody is going to get him, I suspect it is going to be me.”

All the other acquisitions Hachette has undertaken conform to some sort of commercial logic; by comparison, George seems an exorbitant endeavor. Pecker insists that it’s a wise business move: that the magazine will be a good vehicle for advertisers who already appear in the car or audio books, and that his research indicated there’s an audience for a general-interest political magazine, with or without John Kennedy. That said, it’s unlikely that Hachette would have started a political magazine if Kennedy hadn’t shown up to do it. Pecker thinks he can turn Kennedy into good business. “John Kennedy,” he says, “has a good name in the industry [of politics]” — which is a bit like saying Mother Teresa has a good name in the sainthood industry. Pecker is relentlessly, magnificently prosaic. While other publishing companies turn their editors, ordinary people, into celebrities (Tina, Anna, Liz), Hachette is valiantly trying to turn a celebrity into an ordinary person.

_

In Unzipped, there are appearances by several of the fashion-magazine world’s top personalities. André Leon Talley, formerly Vogue’s creative director, vamping around a tarot-card table; Polly Mellen of Allure, making sibylline pronouncements about hem lengths. There’s also an appearance by Gilles Bensimon, the creative director of Elle, and several of his team. They shuffle, uncolorfully, into Mizrahi’s studio, look at a few clothes, and don’t say anything quotable: classic Hachette, really.

Gilles Bensimon and his friend and boss, Régis Pagniez, the publication director of Elle, don’t have the profile of their equivalents at other magazines, though at Hachette, they’re notorious. Elle has long been Hachette’s flagship, but it’s also been an incongruity among Hachette’s fleet of trade publications, a luxury yacht leading two dozen fishing boats. lt is a flagship, it might be added, whose captain has a Napoleon complex: Pagniez has seen an almost annual turnover of both publishers and editors — the former unable to work with the corporate bosses, the latter unable to work with him. (Even Jean-Louis Ginibre doesn’t visit the Elle floor, as a result of a feud dating back to when Pagniez, who had been working as publication director of Elle Decor, was taken off the shelter magazine for overspending.)

“I survived eight editors and five publishers,” says John Howell, who worked at Elle for six years until Amy Gross was hired. “All the important things happen in an elevator or the hallways. There’s lots of fights. It’s a Latin logic. People think of France and they think of Voltaire and reason and philosophers — forget it. They are a Latin people: They are disputatious; they are illogical; they are volatile.” And, says Howell, they are oblivious to the ways of American journalism. “Régis would have dinner with somebody in France, and he would say. ‘Here is a photograph: It is the new girlfriend of Polanski; we must do a story.’ l would say, ‘Fine, what’s her name?’ ‘I don’t know, but she is going to be in a movie.’ ‘Which movie?’ ‘I don’t know.’ So you find out she is Emmanuelle Seigner and that French Elle has done a story on her; so you call French Elle to verify some of these facts, and they say, ‘Well, I don’t know, we were drinking Champagne, l threw away my notebook,’ and everything in their story is wrong. In French journalism, it’s much more a concept of philosophy, and impressionism, and writing, with often a very loose relation to the most boring facts: what’s her name, how old she is, when she met him.”

After a brilliant start in the late ’80s — when both readers and advertisers were ready to vote Anything but Vogue — the magazine foundered in the early ’90s. In order to persuade Amy Gross to come and reinvent the editorial content of the magazine in March 1993 it was necessary to rein Pagniez in: Gross was permitted to bring her own art director for her feature pages, and the two halves of the magazine operate almost independently. Gross has long been chafing at the restrictions of the Elle formula, though: “A lot of the stories that she would get previously she always felt would be perfect for Mirabella,” says David Pecker. Giving Gross Mirabella to play with is a typical Hachette move: a combination of inspired brilliance and incredible cheapness. Gross is a talented editor — you can see her thinking on the spot, always a good sign — but having the same person in charge of the editorial of two magazines does seem to be limiting the sensibility gene pool a little. Gross herself says she treats Elle and Mirabella like two little daughters whose names she keeps mixing up. Those who joined the cult of the magazine early on will probably applaud the relaunch (new tag line: “A Sign of Intelligent Life”), which takes as its model the original Mirabella — no great surprise, since Amy Gross was a founding editor of that magazine. But the lineup for the first issue (writing by Meg Wolitzer, Jane Smiley, Mary Gaitskill) sounds a touch predictable.

Régis Pagniez will be far less involved with Mirabella than he is with Elle, though he’ll still be on the masthead, as will Bensimon — who will not, however, be shooting for the magazine. Even so, Pagniez remains top dog at Hachette: When last year a writer for The Modern Review who was comparing the editors of the top American fashion magazines called the Elle publicity folk for a copy of Gross’s résumé, she was sent a copy of Pagniez’s instead. And for alI the talk of budgetary prudence, Pagniez and Bensimon still manage to lunch at Le Bernardin often. “They would go out to lunch and we would all be eating Chinese food in the office because we would all be working so hard,” says one former Elle worker. “I remember Gilles sticking his head in and saying, That is shit you eat; that is so disgusting.’ There was that sort of French snobbishness: the best food, the best this, the best that.”

It is in the company of Pagniez and Bensimon that the original Frenchness of Hachette is preserved. The two converse in French when there’s not a third party present, which is natural enough, and sometimes when there is, when it becomes a kind of private language. They interrupt each other’s thoughts and finish each other’s sentences: When, in an interview, Bensimon blunders into calling the quality of Calvin Klein’s clothes “a disaster,” Pagniez moves quickly to repair the faux pas. Bensimon, who shoots almost all of the fashion pictures in Elle (and even went through a period of using fake bylines to disguise the fact), is casual and careless in conversation, with an occasional inclination to talk a little dirty: He drops frequent references to his romantic conquests (he was married to Elle MacPherson but left her for Rachel Williams) and admits that he is terrified of the American concern with sexual harassment. Pagniez, who has been an associate of Filipacchi for more than 30 years, is dapper, and careful in his speech — though a sometimes tyrannous monstre sacre to the Elle staff. Both Pagniez and Bensimon are in constant touch with Filipacchi — they both praise the leadership of David Pecker, but it’s clear they don’t exactly need him. Even as Elle went through its roughest patches in 1991, Pagniez and Bensimon were unassailable within Hachette, and theirs is a combination of overt humility and understated arrogance: They discuss the necessity to watch the competition but are convinced of the rightness of Elle’s mission.

“Now we do more in advance,” says Bensimon. “Normally we never look at other magazines, and now we have to.” ’

Pagniez: “The competition is good.”

“We are not the kind that is going to quit.”

“They have to fire us.”

“Or kill us. Kill us would be better.”

_

Daniel Filipacchi would prefer not to emphasize Hachette’s original Frenchness: “What I like about our company,” he says, is that it is really an American company. Like Hearst or Condé Nast. The aggressive assertion of Hachette’s U.S. credentials is understandable: To the extent that David Pecker runs the company, it is thoroughly American. And it helps Hachette to be thought of that way: When the French first arrived

in New York, they didn’t recognize the need to adapt to American ways and were seen in the industry as arrogant. That perception has dwindled; it doesn’t serve Hachette’s interests to be seen as a corrupting alien influence, especially when there’s some truth to the accusation.

But in any case, it is missing the point to think of Hachette’s different way of doing things as strictly French — a perspective that makes about as much sense as it does to think of Rupert Murdoch as essentially Australian. Filipacchi, like his friend Murdoch, is the owner of a worldwide media network with EIles in 26 countries, and plans to launch editions of Premiere in such far-flung places as Singapore and Japan. As with Murdoch,

what’s significant about Filipacchi is his not-Americanness, rather than his Frenchness; both are international businessmen, operating beyond borders.

But it’s worth thinking of Hachette as, at least in part, a foreign power — with the purpose of praising, not burying, it. Hachette is not the only European concern showing an interest in investing in American culture; and investment in American culture is, Americans can agree, a good thing, whoever is doing it. Like fellow European conglomerates Bertelsmann, the German media company that owns Bantam Doubleday Dell and recently bought a package of women’s magazines from the New York

Times Company, and Holtzbrinck, another German publishing concern, which last year bought literary publishing house Farrar Straus & Giroux, Hachette is showing more imagination and energy in supporting American publishing — for profit, of course, not for charity — than many locals are, for which it deserves

some credit.

For the culture in which Hachette invests, though, Americans have only themselves to blame. While Hachette has acquired some quality magazines, like Premiere, Mirabella, and, presumably, George, it’s not averse to selling fluff too. Take TopModel, one of Hachette’s newest magazines. TopModel is Daniel Filipacchi’s idea of a really great magazine: It provides a cunning means of recycling fashion photographs already taken for other magazines by reprinting them next to inconsequential stories about the models’ lives. The text in the American edition is poorly translated from an already appalling French. (Top is used as an abbreviation for top model, which ought to go over well in gay circles: 24 HOURS WITH A TOP could well be a headline from Honcho.) The design is cloned from Elle. Some Hachette folk, even high up in the company, are a bit embarrassed by the publication.

It is, needless to say, a huge success.

→ Continue reading at Vulture