Two strapping young lads stood on the roof of a black Mercedes hawking espressos, IPAs, and $42 sunscreen. Their ad hoc storefront is an elevated metal stand mounted atop the car, shaded by a blue and white beach umbrella—this scene was one of the most memetic images I encountered at the sixth Chicago Architecture Biennial (CAB6), which opened to the public on September 19. The Pavlovian dog in me took out my phone, snapped a photograph, and posted it on social media, like many other passersby outside the Graham Foundation.

Sam Chermayeff’s slacker-chic cafe was indeed a hit on Instagram, but to my dismay, I quickly learned the goofy provocation was effectively a billboard for Hard Sun, a boutique sunscreen brand. The piece was uncritically applauded by MOS cofounder Michael Meredith at a Graham Foundation panel as one of his favorite exhibitions. Sure, it’s cute, but what does it have to do with the CAB6 theme, Shift: Architecture in Times of Radical Change?

“We are in a moment without canons, without a center,” said artistic director Florencia Rodriguez, describing the curatorial intent behind the theme she chose for journalists at the Graham. “How do we make meaning out of this?”

As in past years, CAB6’s installations are spread across the Chicago Cultural Center, Graham Foundation, and other venues, like Stony Island Arts Bank. During my visit, I found a discrepancy between the gravity of the political moment CAB6 sought to address and the aloof joviality of some exhibitions. While ICE and DHS are swarming the streets of Chicago, CAB6’s architects are making what appears to be large balloon animals, metal benches with seats that say “this is a joke” and “how antisocial,” and tongue-in-cheek advertisements for luxury skin-care products.

Propositions, Critiques, and Interpretive Reconstructions

Thankfully, there are ample exceptions. Rodriguez, who hails from Argentina and teaches at University of Illinois Chicago, assembled an impressive roster of North and South American architects. Some participants rose to the occasion and issued apt responses to Rodriguez’s curatorial brief of making architecture in “times of radical change”—which I interpret as fascism and global warming. Others withdrew their works in the weeks leading up to the opening to protest Crown Family Philanthropies, which supports CAB6’s educational programming. (Crown Family Philanthropies has a major stake in General Dynamics, a weapons manufacturer that profits from Israel’s military campaign in Gaza.) In the former camp, at Stony Island Arts Bank, WAI Think Tank’s Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García staged A Loudreading Tribune, an immersive installation that emphasizes justice and collective learning.

A Loudreading Tribune features an interpretive reconstruction of El Lissitzky’s Lenin Tribune, an anticolonial library, and other ephemera, including photography of Frantz Fanon swaddled by houseplants. We see a keffiyeh and a copy of Palante, the Young Lords Party newspaper. WAI displayed an original tenebrist painting—my personal favorite work on view at CAB6—featuring a small, painterly montage of El Lissitzky’s Beat The Whites With The Red Wedge (1919) with a hammer and sickle and Caribbean fruits in the foreground, almost like an avant-garde Caravaggio inspired by the poetry of Puerto Rican anarchist Luisa Capetillo.

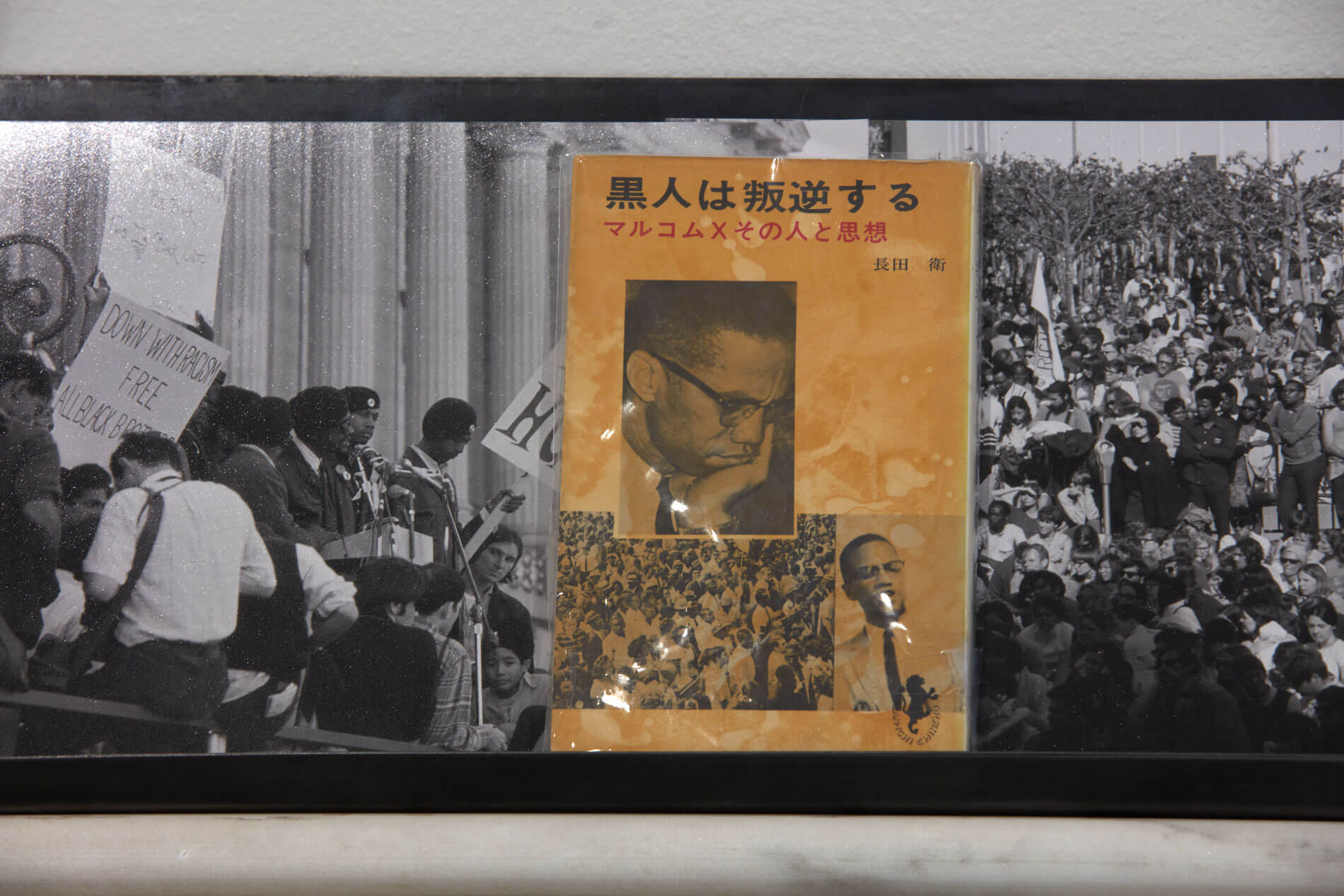

The installation echoes a solo show by Theaster Gates now at the University of Chicago’s Smart Museum of Art. Unto Thee isn’t part of CAB6, but the partner exhibition by Gates is stocked with Marxist literature that thematically ties into similar realms. There, Gates placed an original Josef Albers from his personal collection next to a book of Malcolm X’s writings translated into Japanese by Yuri Kochiyama, in what Gates calls a mantle for the Japanese civil rights activist. Taking these Chicago-based shows together, Gates and WAI Think Tank delve into internationalist, anti-imperialist, revolutionary artistic practices that defy borders and time.

Iman Fayyad’s In the Round is the most formally compelling piece at CAB6, architecturally speaking. Installed at the Chicago Cultural Center, Fayyad’s 1:1 scale project conjures Félix Candela’s poetic, hyperbolic concrete forms. Fayyad, founding director of project:if, achieves a sculptural complexity similar to Candela’s with quotidian plywood veneers. Fayyad told journalists that the whole object weighed under 300 pounds and that she envisioned its material assembly system getting deployed for disaster relief housing or any other scenario that might demand quick, dignified shelter.

Like In the Round, Oscar Zamora and Michael Koliner’s Air Vapor Barrier explores material innovation. However their intervention is more critique than proposition. Zamora and Koliner built a pitched roof, leaving 3M insulation membranes exposed, supported by rudimentary wood rods. For Zamora, the installation addresses how architects in the Global North are looking toward “tropical architecture” in the Global South to make ecologically sound buildings. In reality, the asymmetrical flows of neocolonialism dictate an opposite effect, where the Caribbean is inundated by mass-produced goods from the U.S.

Air Vapor Barrier recalls a recent text in Brooklyn Rail by Orlando Bentancor I came across describing “the uneven geographies of the Global South, where technology arrives not as seamless innovation but as salvage, residue, bricolage. In Montevideo, the future doesn’t gleam, it rusts. And it is precisely this rust [through which] another vision becomes possible. The paradox of our time is stark.”

Questions of domesticity, comfort, and repose reappear cyclically throughout CAB6, prompting Zach Mortice to call it “a soft Chicago architecture biennial for hard times” in his Bloomberg write-up. Not unlike Air Vapor Barrier, The Global Home, a film by Space Popular’s Lara Lesmes and Fredrik Hellberg, examines how logistical infrastructures inform movement, behavior, and social patterns. The Linen Closet by Jason Campbell and ellProjects features 50 blankets that friends and family gifted the Chicago-born artist, each imbued with its own memories and associations with home. Iker Gil’s MAS Context Reading Room spotlights local talent with Common Chicago, showcasing local practitioners to watch out for.

Inhabit, Outhabit, a group show, assembles 29 impressive multifamily housing projects from around the world by French 2D, SO – IL, Centro Cooperativista Uruguayo, HHF Architects, Kashef Chowdhury/URBANA, adamo-faiden, Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects, MASS Design Group, Oshinowo Studio, PRODUCTORA, Michael Maltzan, URBANUS, Mariano Clusellas, José Cubilla, APPARATA, and other architects. Scale models, drawings, and other modes of representation offer a compendium of innovative solutions to the global housing crisis. At Graham Foundation, Stan Allen’s expansive portfolio, with an emphasis on his residential work, is also on view through line drawings and text, curated by Michael Meredith, with graphic design by Studio Lin.

Memory, Maintenance, and Refusal

Circularity, material upcycling and innovation, maintenance, and adaptive reuse are other recurring themes at CAB6 and rightfully so. Shifting Reuse and Repair by La Dallman at the Chicago Cultural Center certainly fits this bill. The tallest of the CAB6 installations, it features a fragment of a shuttered granary built in 1901, in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin. La Dallman essentially took a utilitarian structure slated for demolition and gave it new life. Some Repairs by Davidson Rafailidis, Minor Tectonics by BURR, and Tamara Kostianovsky’s Nature Made Flesh likewise focus on adaptive reuse through model making and storytelling. Fragments of Disability Fictions by Ignacio G. Galán, David Gissen, and Architensions takes up the vital, immensely pressing task of centering issues related to architecture and accessibility, through the prism of the New York City subway system and other alienating spaces for those living with disabilities.

Outside the Museum of Science and Industry, where the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair was staged, balsa.crosetto.piazzi and Giorgis Ortiz ideated Traces, which features 10,000 dry-set bricks that hearken to the fair’s temporary “Great Buildings.” After the biennial ends, the architects will reuse the bricks at a future undetermined site. Akin to Traces, The Crystal Forest by Sayler/Morris simultaneously examines the relationship between industrialization, degradation, glass, and world fairs, namely the 1851 Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London.

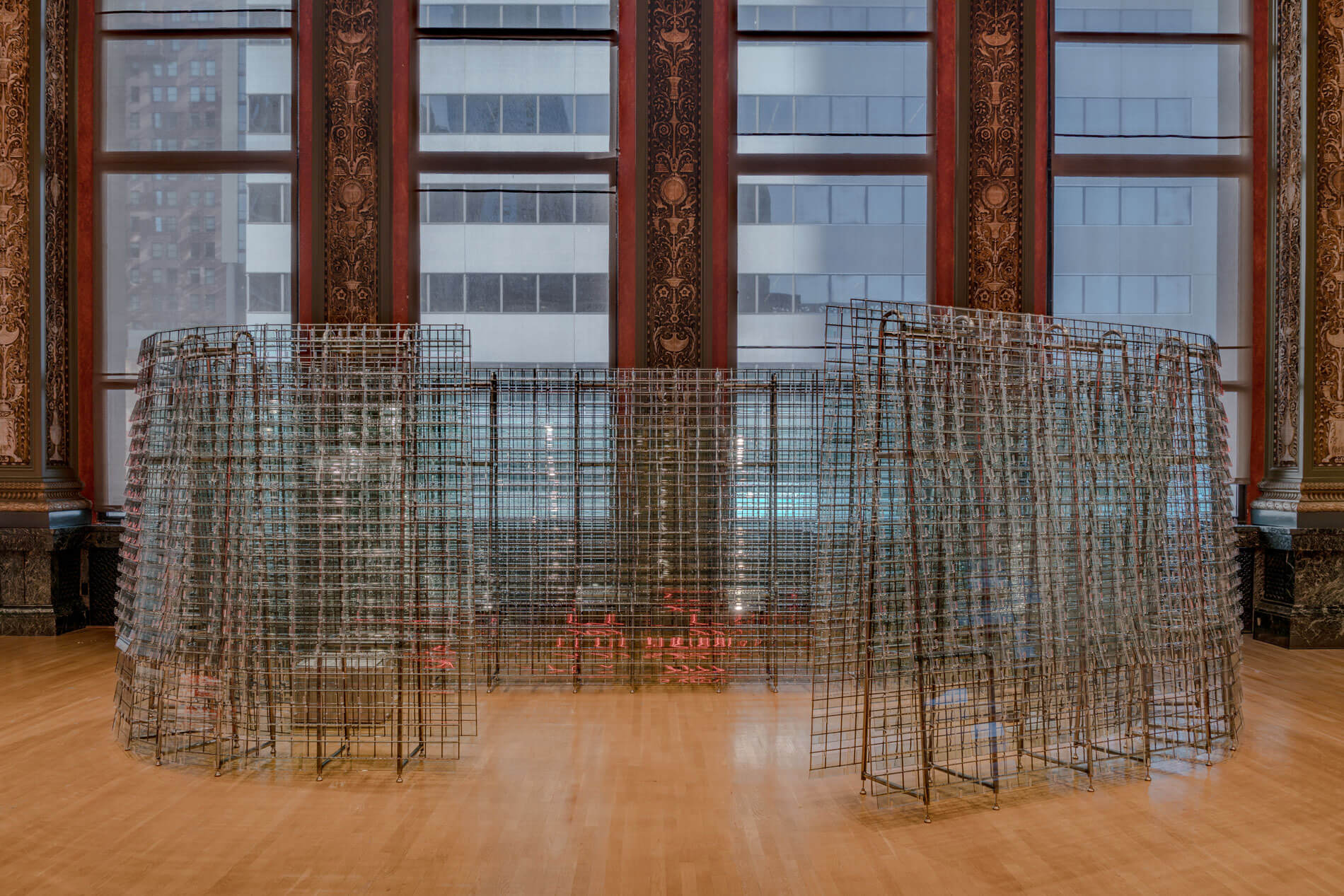

Our Second Skin, The Skin of the City by RADDAR likewise prodded glass’s dazzling potential. RADDAR assembled 2,500 glass pieces shaped like fish scales; this is meant to emphasize the notion that “glass has turned into a kind of skin, carrying our hopes, politics, and ideals,” RADDAR founder Sol Camacho said in an artist statement. Camacho’s words paradoxically evoke that old Walter Benjamin adage “Glass has no history.” At Stony Island Arts Bank, Abigail Chang had similar aspirations for Liquid Glass. Later this fall, an installation about raving by TAKK and Ivan Munuera will take place inside the Hancock Building, along with more than 20 other new pieces as part of CAB6.

Nevertheless, making my way through CAB6, it was hard not to think about the elephant in the room. The CAB6 participants who withdrew before the September 19 debut to protest Crown Family Philanthropies were Ethel Baraona Pohl, Anna Puigjaner, and Pol Esteve Castelló of ETH Zurich; María Buey González, C+ arquitectas; Lacol Arquitectura Cooperativa; MAIO; and Amaia Sánchez-Velasco, Gonzalo Valiente Oriol, Jorge Valiente-Oriol of Grandeza Studio. Others made their position known through their work: Cosigners of the letter Lesme and Hellberg of Space Popular, for instance, inserted a disclaimer into their video piece to declare their opposition to the funding and in support of their colleagues who exited the biennial. Perhaps these acts of refusal were the most potent, admirable demonstrations of “architecture in times of radical change.”

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper