Natural Attachments: The Domestication of American Environmentalism, 1920–1970 by Pollyanna Rhee | The University of Chicago Press | $32

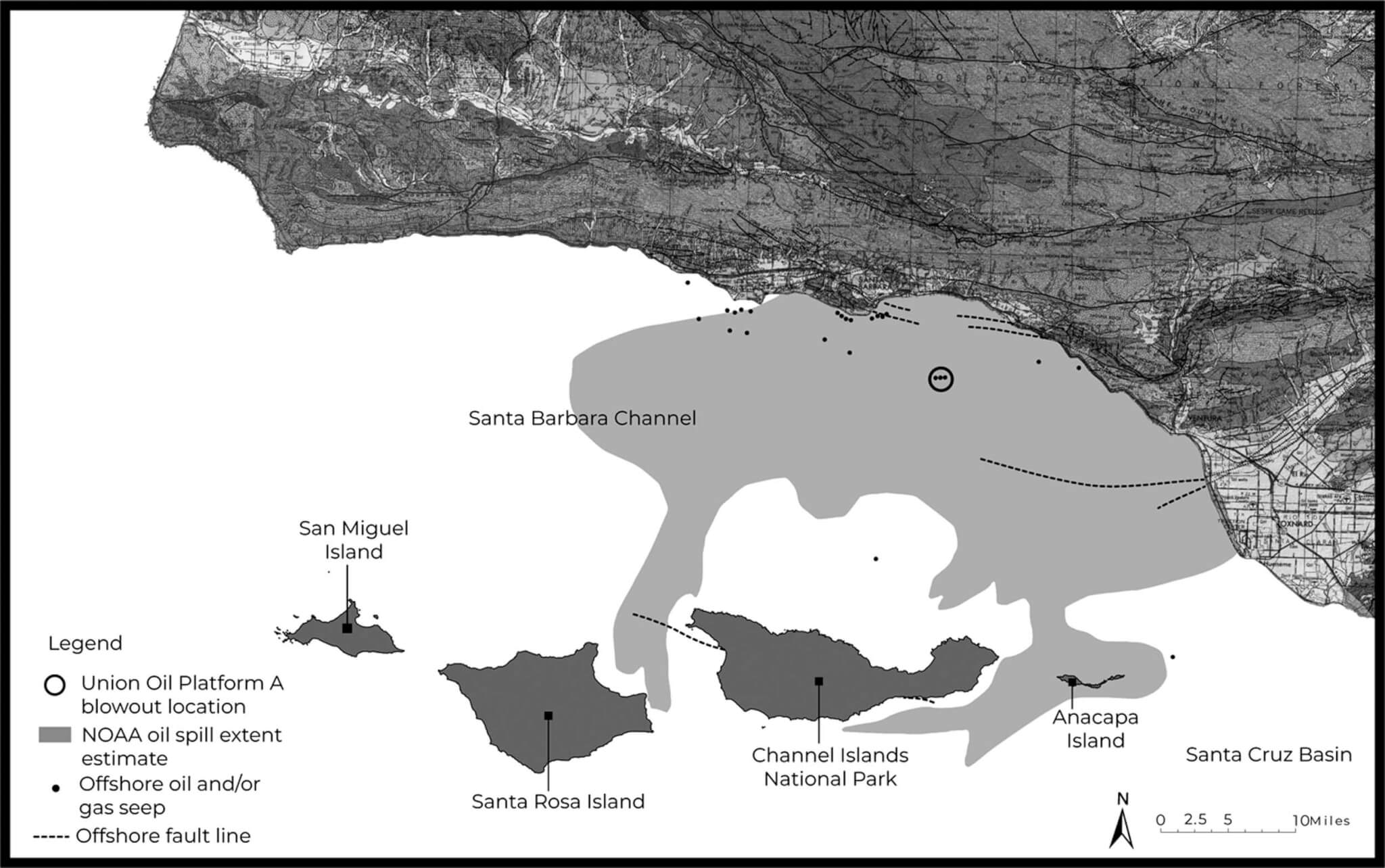

The standard historical narrative of American environmentalism is fairly well established. With precursors in the conservation movement of the early 20th century, the environmental movement really began with postwar concerns that urban sprawl and pollution were coming to outweigh the benefits of economic growth. The year 1969 served as a catalyst, with the Cuyahoga River fire and the Santa Barbara oil spill sparking citizen initiatives like Earth Day and policy changes such as the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970.

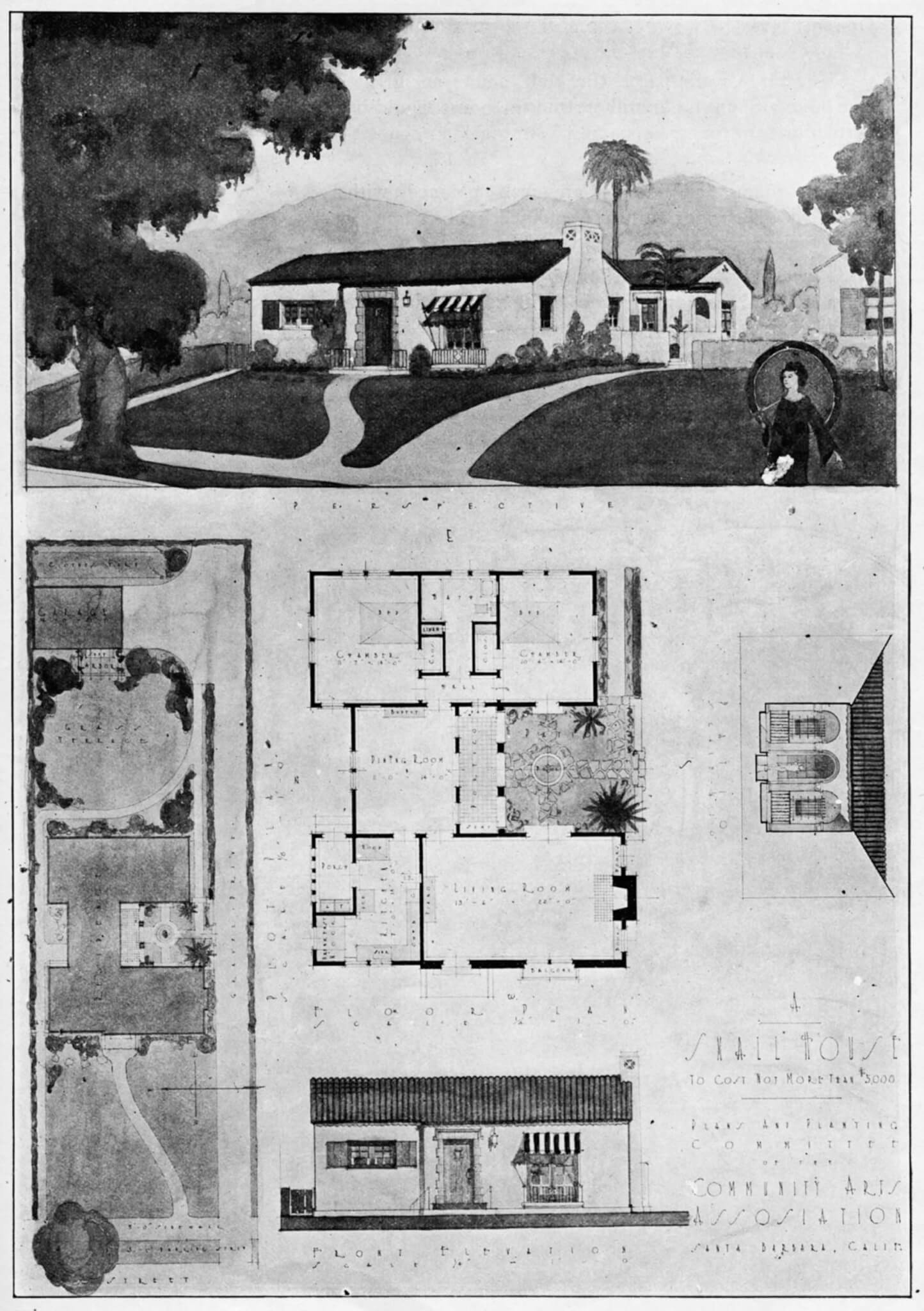

The Santa Barbara spill anchors Pollyanna Rhee’s new book, Natural Attachments: The Domestication of American Environmentalism, 1920–1970. But rather than moving forward from the 1970s, Rhee traces the spill’s mobilizing power to the development of the wealthy coastal town of Santa Barbara in the 1920s. She argues that an idyll of “natural” living, which homeowners reinforced through architecture, planning, and historic and landscape preservation, paved the way for the rise of what she calls “ownership environmentalism.”

Ownership environmentalists aimed to create “ideal domestic conditions,” protecting the houses they owned and the high quality of life in their communities. Since ownership environmentalism was largely motivated by property value, those who did not own a house or who lived elsewhere were given less say over environmental policy decisions. According to Rhee, ownership environmentalism gave the Santa Barbara oil spill a rhetorical power far beyond that of other oil spills, of which there were nearly 100 in the first half of 1969 alone. But at the same time, it leveraged that power in service of economic elites rather than a broader vision of environmentalism as part of social change.

Natural Attachments is split into two parts. The first half begins in the wake of the 1925 Santa Barbara earthquake, which provided an opportunity for local power brokers to remake the city into a homogeneous, Spanish colonial vision that catered to the city’s white upper- and middle-class populations. This intervention was the beginning of Santa Barbara as a symbol of the West Coast good life, a reputation Santa Barbarans furthered through advocacy for single-family homeownership and domestication of “exotic” plants. The second part focuses on the postwar era’s attempts to preserve this quality of life, first through antigrowth policies and neighborhood associations and eventually through environmental advocacy after the oil spill.

Rhee’s book is an ambitious, and largely successful, attempt to bring together environmental history and architectural history through a case study of one California town. It is particularly good in its focus on environmentalism in the second part of the book. There, Rhee shows how Santa Barbarans interpreted the postwar California population boom as a threat to their exclusive domesticated utopia. “Advocating for protections for existing homeowners,” she writes, “gave rise to an environmental determinism that. . . justified the belief that the most valued regions of California were already full.” In a city where studio apartments currently start at around $1,750 a month, Rhee’s discussion of the postwar period is a prescient reminder that Santa Barbara’s ongoing housing crisis is part of a longer history of exclusion.

The oil spill gained mainstream attention in large part because of influential Santa Barbara residents like former Ford Foundation president Robert Maynard Hutchins and ecologist-cum-racist-demagogue Garrett Hardin. Santa Barbara’s renown for beauty paved the way for national outrage: “If it happened in Santa Barbara, then presumably very few places could assume protection,” as Rhee puts it. Despite the frequent effectiveness of ownership environmentalism, Rhee writes, it “made no demands for radical changes in society” and in fact stood in “marked contrast” to the social conflicts of the 1960s. Rhee makes clear that Santa Barbarans’ fury over the oil spill shaped environmental policy, while also showing how they failed to consider their own car-bound lives—Southern California led the world in gasoline consumption—as contributing to the oil slick covering their beloved beaches. This fundamental contradiction of ownership environmentalism dates back to the construction of oil wells in the city in the 1920s, as historian Michael R. Adamson recently wrote: “Even those who protested drilling in their backyards. . . supported regional automobility sustained by petroleum extraction in someone else’s backyard.” In concrete terms, this meant opposition to wells in the Mesa neighborhood, but support for extraction in Elwood, a few miles west of town.

Natural Attachments is not without flaws. Although Rhee’s narrative centers urban development, there is a notable lack of analysis of the actual construction and design of Santa Barbara, and the intellectual currents Rhee traces can remain frustratingly disembodied. For instance, the first chapter, which focuses on boosters’ framing of design as a way to align with the natural environment, tells us little about the construction that followed the 1925 quake. This lack is particularly noticeable where Rhee emphasizes the exclusionary and often downright racist attitudes of the Santa Barbara elite. Did such attitudes translate neatly onto the built environment, or were they contested by marginalized groups? Albert Camarillo has noted that by the 1920s, Mexican and Chicano workers filled most manual labor jobs in Santa Barbara’s construction industry—from Angulo Tile Works, which provided an essential material for the Spanish colonial fantasy, to brick- and lumberyards, street crews, and construction sites, as well as gardening crews. Such workers may have left fewer records than the figures Rhee focuses on, but they were no less essential to creating and maintaining Santa Barbara’s domestic idylls.

The book’s focus on ideas will also leave readers who have not been to Santa Barbara without a clear sense of what the place actually looks like. Natural Attachments comes in at just 160 pages of text, with a handful of black-and-white images and maps. A push for brevity may have led to the excision of important spatial analysis and additional images that would bolster and perhaps further nuance Rhee’s narrative. In the end, Natural Attachments is more environmental history than architectural history.

Rhee concludes that “weaponizing nature to protect the quality of life for the few shows how environmentalism can be complicit with maintaining or even exacerbating social and spatial inequalities.” She argues that we need to own up to the exclusionary history of ownership environmentalism to move beyond it. Rhee’s thesis takes on new context in our current political landscape, as the second Trump administration guts environmental protections. Is Rhee’s criticism of the environmental movement pointless or even divisive at a time when the Right is systemically dismantling environmental policies?

I think not. In 2013, Elon Musk got into an argument with Larry Page, Google cofounder and venture capitalist. Page mocked Musk for rejecting Page’s faith in an “artificial general intelligence,” a sort of digital supreme being that would oversee the future once humanity was destroyed by global warming. Literary critic Matt Seybold points out that Page had already given up on the future of humanity at a time when he was “arguably the foremost poster boy for market-based solutions to climate change. . .renewables, recyclables, clean-burning fuels, carbon capture and carbon credits, airships, asteroid mining.” The last decade has shown how easily a veneer of ownership environmentalism can yield to nihilistic neoliberal antihumanism, often enriched by science-fiction fantasies of Matrix or Dune varieties. Although Rhee’s book ends in 1970, her research provides insights that are every bit as valuable for diagnosing today’s socioenvironmental condition as they are for understanding its past.

Alexander Luckmann is a PhD student in architectural history at UC Santa Barbara. He writes about the built environment.

This post contains affiliate links. AN may have a commission if you make a purchase through these links.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper