Houston is a multicultural mecca, and now it is home to the first Ismaili Center in the United States and just the seventh in the world. (The other centers are in London, Vancouver, Lisbon, Dubai, Dushanbe, and Toronto.) The 5-story, 150,000-square-foot building designed by Farshid Moussavi Architecture (FMA) with DLR Group and its 9 acres of gardens by Nelson Byrd Woltz will serve as a cultural and ambassadorial center for Ismaili Muslims. On November 6, the center held an opening ceremony attended by civic and cultural leaders, including leaders and supporters of the Ismaili community. It will open to the public in December.

A Legacy Continued

The Ismaili community is a sect of Shia Islam with between 12 to 15 million followers around the world. The Houston area has the largest community of Ismailis in the United States, numbering between 35,000 to 40,000. The journey of this cultural complex began in 2006 when the Imam, spiritual leader of the Ismaili people, His Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan IV, purchased the central 11-acre parcel with a vision for a community center that offered civic and spiritual programs.

The project proceeded slowly: A design competition resulted in a shortlist that included FMA alongside David Chipperfield Architects, Studio Gang, and OMA; FMA was awarded the project in 2019. Construction began in 2021 with a wider design team that included FMA, Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects, DLR Group, AKT II as structural engineer, and McCarthy Building Companies as the general contractor.

Sadly, Prince Karim Aga Khan IV didn’t live to see the results of two decades of work: He died earlier this year at the age of 88. His son and successor, His Highness Prince Rahim Aga Khan V, has completed his father’s project.

A Center for Connection

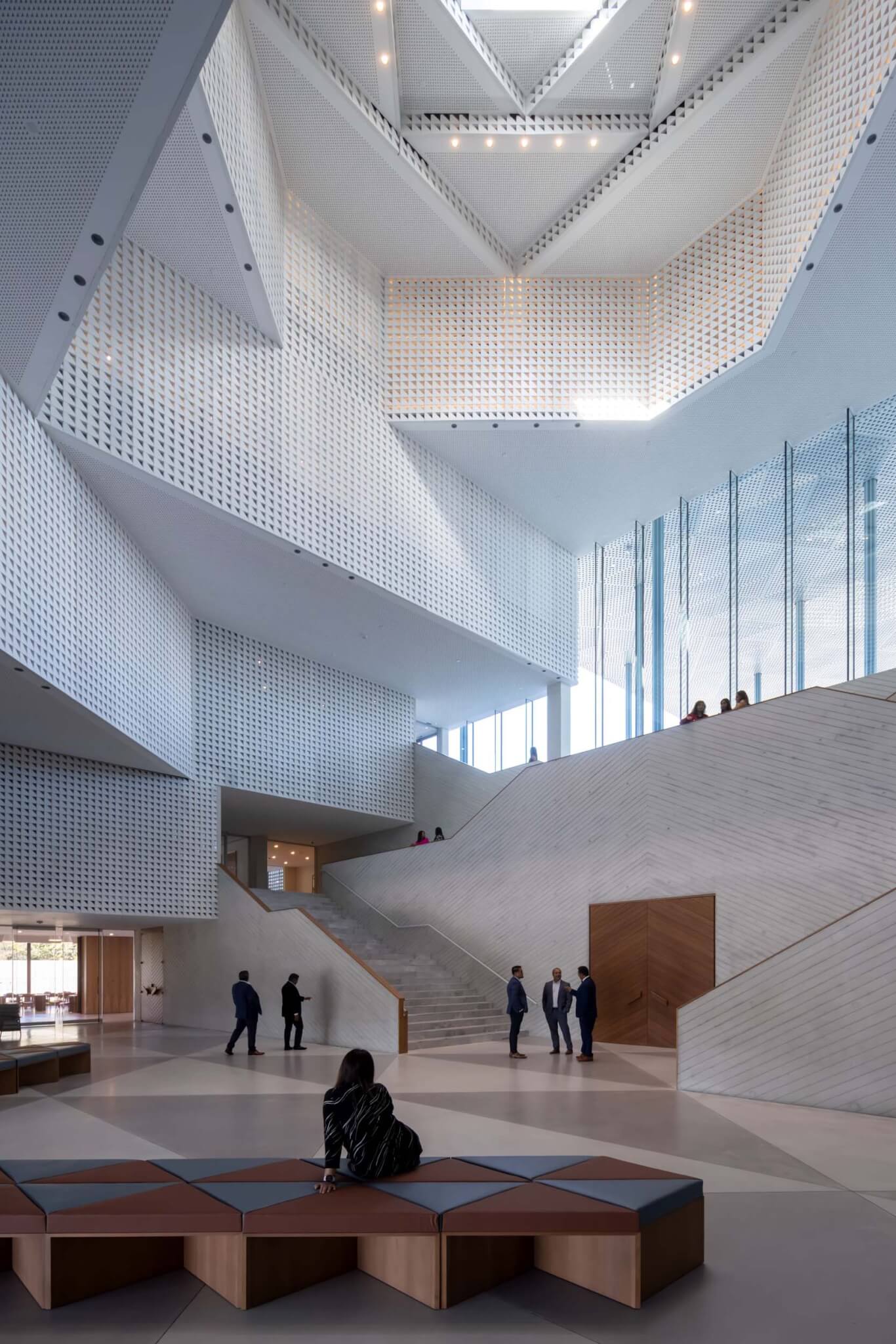

Inside and out, Moussavi’s design plays with contemporary expressions and methods of traditional Islamic architecture. Farshid Moussavi, who is of Iranian heritage herself, said, “One of the methods was to be inspired by the heritage—the architectural heritage of the Muslim world. But whatever you pick of that heritage [must] speak to the contemporary American city, and to use them in a way that will also speak to future generations.” Simplicity achieves tranquility, ornament is given function, and Persian architecture thrives in a Houston landscape. Traditional Persian motifs, including ceramic mosaics, perforated screens, blue tones, and geometric patterns are expressed across the floors, soffits, and alcoves of the impressive building. Triangles—a key symbol in Islam— appear at multiple scales across the project, creating tawhid, or oneness. They are embedded within the site’s organization, the garden tile patterns, the building’s columns, and even its soffit perforations.

While it is a place of worship, the prayer hall only occupies about 8 percent of the site, and over 90 percent of the square footage is programmed to be secular. The center’s three main functions—worship, learning, and social connection—are equally significant, a reflection of the Ismaili community’s values. Omar Samji, spokesperson for the Ismaili Center, said, “Our hope is that we are able to do, on a much enhanced or larger scale, what the community does today in terms of engagement on service projects in arts and culture, in interfaith dialog, and even just in bringing people together—the notion of creating connections, a place where it is easy to create connections, because it’s an open space, because it is specifically designed to be a place where people interact and people find commonality.”

Each function is housed within one of the three volumes of the building, which can support concurrent activities and are connected by atriums. The central volume, crowned with a 68-foot-high oculus held up by Vierendeel trusses, houses the jamatkhana, or prayer room, which is entered between staircases lined in board-formed concrete. The west wing includes the cafe and social halls, while the east wing houses learning spaces, a black box theater, a library, an exhibition area, administrative offices, and council chambers.

Suitable for the hot and humid Houston climate, eivans, open-columned verandas typical in Persian architecture, bring abundant light into the interior and open up each side of the building as an invitation to the rest of the city. The eivans are supported by 49 slender steel columns, an homage to the 49th Imam of the Ismaili community who made this project possible. The main elevated eivan overlooks the north gardens and can accommodate large gatherings. On the opposite side of the complex, a 150-foot-wide patio frames the main entrance to the south, a nod to the worldwide use of the porch as a threshold. Triangular perforations in the canopy’s UHPC panels provide acoustic absorption to combat nearby traffic noise.

The site’s strict north-south axis creates a clear organization for the building and the gardens on either side, but internally the 12,240-square-foot prayer room at the center is rotated 45 degrees to face Qibla, the sacred direction for prayer toward Mecca. The prayer hall, which holds up to 500 people, features a harmony between the walls, floors, and screens for peaceful reflection and collective prayer. Inside, the deep brown, CNC-perforated walls feature stylistic Kufi calligraphy spelling out “Allah,” “Muhammad,” and “Ali,” all names for God in Islam. The translucent ceiling creates an illusion of endless layers with a thick fabric stretched over thousands of LED lights and a delicate two-layered aluminum screen. It generates abundant soft, diffused light within the space. Thanks to some structural gymnastics, worshippers would never guess that a social hall with seating for 600 is located above this boundless sky.

Outside, the textured rainscreen facades are constructed with individual pieces of stone threaded onto thin tension rods, like a rug being weaved on a loom. This “turns it into a tapestry of stone,” Moussavi said. The resulting lightness of the facade gives it a weightless feeling meant to represent the spirituality and openness of the community within. The design team delivered a building that will last well over a century, aiming for LEED gold certification. The stone cladding is a low-carbon spec, and the concrete is mixed with fly ash and slag to reduce CO₂ emissions by 30 percent.

Across its elevations, the stone varies between circular or triangular corner perforations, parallelograms, and toothed triangles. Light filters through the glass cutouts within the stone, acting as a mashrabiya, or a screen that is common in Islamic architecture. As one walks around the building, the changing geometries provide different levels of privacy and openness beyond the screen. As the sun sets, the illumination reverses directions: The light spills through the stone screens, and at night the building becomes a beacon of light.

Bayou Adjacent

The Ismaili Center’s narrow rectangular site sits at the busy intersection of Allen Parkway and Montrose Boulevard just west of Houston’s downtown. The site elevation drops 27 feet as it runs north toward Buffalo Bayou, reminiscent of ancient Persian gardens stepping down to a river. The orientation presented an opportunity to showcase the biodiverse transect of Texas through an Islamic lens, as Thomas Woltz explained on site. Situated along a primary axis, each terraced garden represents a distinct ecological region, from the High Plains down to the Gulf Coast Prairie, with native Texan plants, reflecting basins, water fountains, mosaic paving patterns, and shaded spaces for communing and peaceful reflection. At the heart of the north terraces, a broad event lawn and stage create a flexible gathering space for more than 1,000 people for performances, celebrations, and community events.

Migrating monarchs on the way to Canada were already fluttering through the gardens, which have become an oasis for pollinators. The Persian tradition of Islamic landscapes to celebrate a divine order within nature contrasts a sublime and wild view of nature, yet the two cultures complement each other in a quiet balance. Formal geometries of the gardens were filled to the brim with wild Texan plants, and Woltz is patiently waiting for them to grow more. He explains the significance of this harmony, “There has been a deep intolerance in many parts of the world. Home is something ephemeral to many members of the Ismaili community. And if they can come to this center…and find a kind of home that resonates with the greater Islamic world, but is essentially Texas, and know that they are home. Those children raised in this building and these gardens will know the duality of their very nature.”

Given Buffalo Bayou’s flood concerns, the threat is real. The building sits above the 200-year floodplain at the site’s center and highest point. The north half of the gardens, more than a third of the overall area, is designed to flood and incorporates a drainage system and floodwater storage to handle the area’s increasingly frequent severe storm events. More than 800 trees and thousands of perennials stand in the gardens were planted, with each species chosen for its ability to withstand both drought and flood. During Hurricane Beryl in July 2024, the gardens filled with water but drained within 24 hours with minimal debris, demonstrating the stormwater design in action.

A New Chapter for Houston

The Ismaili Center stands central to many cultural hubs near Downtown Houston. Just a few miles south lies the Museum District, home to The Menil Collection, Asia Society Texas, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The Center’s gardens, designed by Nelson Byrd Woltz, join the firm’s growing influence in the city through projects like the 1,500-acre Memorial Park, Rothko Chapel, and Rice University’s quad. In 2011, the Aga Khan and members of the Ismaili community helped fund and install Tolerance—a public artwork of seven statues by Spanish artist Jaume Plensa—just across the street in Buffalo Bayou Park. Even the Center’s immediate surroundings tell a layered story of Houston: Magnolia Cemetery has occupied a lot on the other side of Montrose Boulevard since 1884, while immediately to its east is an open parking garage and a faux-rustic apartment complex.

The openness of the Ismaili community, and consequently its center, amplifies the unique lived experience of being Ismaili in Houston. This latest Ismaili Center stands as a symbol for many Houstonians whose layered identities are shaped by religion and culture as much as place. Sacred space and civic life intertwine in Houston’s newest cultural institution.

Pooja Desai is a Houston-based architectural designer and writer.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper