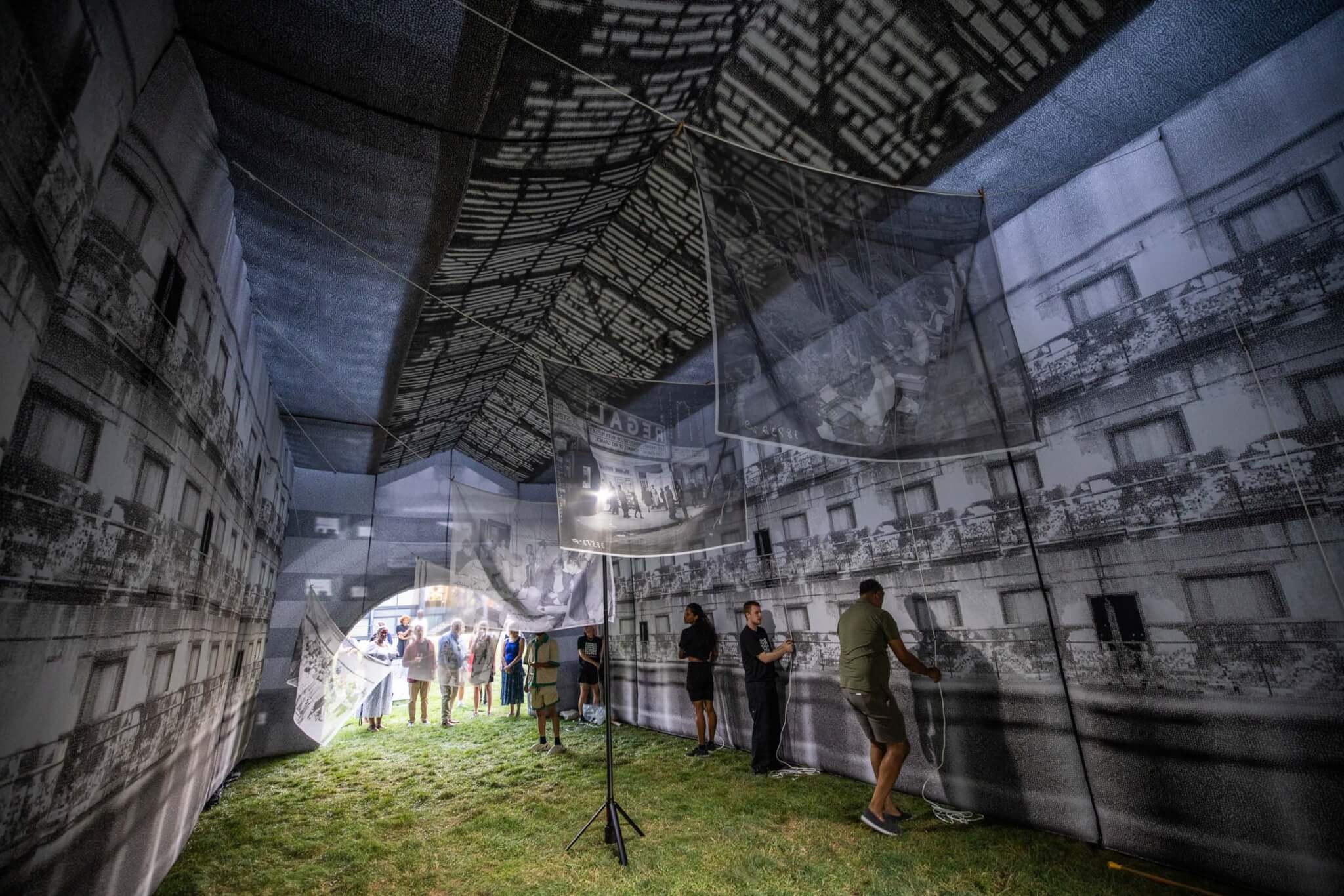

At first glance, a new 30-foot-tall inflatable artwork in Chicago evokes the playful bulk of the bouncy houses that punctuate neighborhood block parties. But a deeper engagement reveals that this is no ordinary moonwalk. Instead of candy-colored vinyl, its skin carries supergraphic patterns: archival images stretched, fractured, and reassembled. Step closer, and the images dissolve into the abstraction of crisp black-and-white triangles and diamonds—leaving a presence that resists being fully pinned down.

The interdisciplinary art collective Floating Museum’s for Mecca is an itinerant, inflatable monument that commemorates sites of disinvested, forgotten, or erased cultural significance in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood. The pneumatic sculpture features scanned and stylized historic photographs of nearly a dozen building facades printed on its fabric membrane, including the first Regal Theater, the Avalon (New Regal Theater), Plantation Café, Savoy Ballroom, ChiAm Café, Pilgrim Baptist Church, and Chess Records. The graphics lining the interior surfaces of the artwork’s central chamber reenact the Mecca Flats apartment building’s skylit interior court and recall its open corridors with ornately detailed iron guardrails. The story and physical memory of the Mecca Flats is the starting point for commemorating this broad collection of buildings that played important roles in the Black experience in Bronzeville during the first half of the 20th century.

On August 9, community members gathered just outside S. R. Crown Hall at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) to witness for Mecca’s inaugural inflation at the location where the Mecca Flats once stood. Originally built as a hotel for wealthy white visitors to 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, the Mecca Flats was later converted into an apartment building that become a hub of Black residential and cultural life, with prominent residents such as Muddy Waters, Katherine Dunham, and Gwendolyn Brooks. As the building fell into disrepair, IIT purchased the Mecca and spent 15 years fighting with residents and housing advocates who opposed the university’s plan to demolish the structure as part of the expanding campus. The Mecca was finally demolished in 1951 to make way for the construction of Crown Hall, widely regarded as one of Mies van der Rohe’s architectural masterpieces.

As the Floating Museum co-directors avery r. young, Andrew Schachman, Faheem Majeed, and Jeremiah Hulsebos-Spofford reflected in a joint statement, “We can no longer view nostalgic images of Mies van der Rohe—enjoying a cigar in the emptiness of S. R. Crown Hall—without also imagining Mecca Flats, collapsed under his feet, and recalling the slow strategic displacement of the African American community signified by the presence of its absence.” While for Mecca is scheduled to “drift” throughout the city over the next year, popping up at parks and community centers to provide a platform for conversations, exhibitions, and performances, the August launch at Crown Hall sanctifies “ghosts” of lost architecture and displaced community that exist underfoot not only at IIT but also at sites of other urban renewal projects around the city and country.

As I previously reported for AN, in 2018, construction workers digging a hole for an infrastructure project next to Crown Hall happened across the multicolored tiled floor of the Mecca Flats basement buried about six feet underground, prompting historians and archeologists to excavate and preserve a portion of the remains. If the campus construction workers inadvertently revealed and agitated the ghost of the Mecca Flats in 2018, then for Mecca’s inflation ritual in 2025 more intentionally conjured the ghost of this lost architecture—and the spirits of the Mecca’s architectural companions from around Bronzeville as well—for a collective moment of reckoning and reconciliation.

When encountering for Mecca, the viewer doesn’t just look at history—they become spatially immersed in its affect. Visitors stand beside the imposing height of its onion dome, walk under its protruding bay windows and turrets that cantilever off from the main volume, feel the wind ripple through its multiple lobes, and walk inside its dazzling interior. for Mecca functions as a kind of embodied elegy, where the body of the viewer becomes entangled with the bodies and persona of the lost buildings.

The visual elegy is disjointed: the fragments of images are slightly mismatched in scale, producing jarring juxtapositions, and optical distortions. This visual friction activates affect by introducing discomfort, wonder, and estrangement. The familiar becomes strange—recognizable urban forms are rearranged just enough to induce a bodily hesitation or a mental double-take.

From a distance, for Mecca appears like a decorated shed, claiming space and asserting presence with its multiple, exuberant facade fragments. But up close, it’s unexpectedly tactile, soft, and pliant—qualities usually associated with intimate furnishings rather than “serious” buildings. This produces a rupture in perception, where intimacy and vulnerability emerge from what first appeared monumental.

In addition to standing as a tantalizing public artwork in its own right, for Mecca also gestures toward future strategies for artists, graphic designers, and architects to explore—tactics that challenge the conventions of static, singular monuments, so often carved in stone and lifted onto plinths divorced from everyday life. Instead, for Mecca proposes spatial graphics that invite immersion, inhabitation, and intimacy, opening new ways to gather publics, share collective memories, and foster belonging. Its immersive affect operates through contradiction: monumental yet ephemeral, historical yet mobile, mournful yet alive. for Mecca is not a precious object. It is generous, communal, and open to interpretation.

In spring and summer 2026, for Mecca will travel to various Chicago Park District sites and former Chicago Public Housing lots.

Author’s note: Portions of this text will appear in the forthcoming book Supergraphic Landscapes: From Public Art to Urban Design (2026) by Joseph Altshuler and Nekita Thomas.

Joseph Altshuler is Assistant Professor of Architecture at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, cofounder of Could Be Design, and coauthor of Creatures Are Stirring: A Guide to Architectural Companionship.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper