Diane Keaton, the Oscar-winning actress who redefined onscreen neurosis in Annie Hall and offscreen devotion in her tireless campaign to save Los Angeles’s architectural soul, died on October 11 in Los Angeles. She was 79.

Known to generations for her quick wit, unguarded laugh, and signature wide-brimmed hats, Keaton spent as much of her life offscreen shaping the built world as she did shaping characters. Behind her eccentric, carefully layered persona was a disciplined preservationist, unfolding in the textures of clay tile, cast concrete, and reclaimed brick. Keaton saw buildings not as static monuments but as living reflections of memory, history, and care.

Actress

Keaton was born Diane Hall on January 5, 1946, in Los Angeles and grew up in Santa Ana, in a midcentury Southern California of tract houses and expanding suburbs. Her father was a civil engineer and real estate broker; her mother, Dorothy, was a homemaker who kept scrapbooks that documented family life, a form of visual storytelling that deeply influenced her daughter. That instinct for collecting and composition would later find expression in photography, preservation, and design.

After studying acting at Santa Ana College and the Neighborhood Playhouse in New York, Keaton gained early notice on Broadway in Hair before becoming a muse and collaborator to Woody Allen, earning an Academy Award for Annie Hall. Her performances, eccentric yet emotionally precise, defined an era of American film, from The Godfather to Baby Boom and Something’s Gotta Give. But as her career matured, so did her fascination with architecture’s narrative power.

By the early 1980s, Keaton had begun collecting photographs of historic buildings, documenting lobbies, ballrooms, and dining rooms resulting in her 1980 photography book Reservations, a black-and-white study of the vanishing elegance of America’s hotels. The project marked the beginning of what would become a lifelong preoccupation with place.

Preservationist

Her advocacy began at home. In 1982, she purchased and meticulously restored the 1928 Lloyd Wright–designed Samuel-Novarro House, a Mayan Revival landmark tucked into the hills of Los Feliz. What started as a personal restoration evolved into a civic mission. By the 1990s, Keaton had joined the board of the Los Angeles Conservancy, lending her visibility and influence to campaigns to save endangered landmarks, including the Ennis House and the Ambassador Hotel.

“Diane celebrated preservation victories, participated in our events, and brought her trademark grace and visibility to the Conservancy’s work—never hesitating to open doors with her name when she believed it could make a difference,” said Adrian Scott Fine, president and CEO of the Conservancy.

The demolition of the Ambassador Hotel in 2005 was a particular heartbreak. The loss of the storied site, where Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated, underscored the fragility of Los Angeles’s architectural memory. Keaton, who had photographed the hotel for Reservations, stood before a crowd of preservationists at a makeshift wake and spoke of the loss “like losing a lover,” she said.

“I felt the loneliness of [The Ambassador Hotel’s] last stand. I heard an echo, an echo, and maybe it was the echo of the ambassador calling me,” Keaton went on. “It was almost as if she was saying to me, she was saying, ‘goodbye, Diane, Keep me in your heart, and next time, try harder.’”

And she did.

In 2019, Keaton appeared before the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors to advocate for the renovation of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), joining fellow preservation-minded celebrity Brad Pitt in supporting architect Peter Zumthor’s controversial redesign. Her stance was less about style than about stewardship, an insistence that the city’s built fabric, old and new, deserved care. Keaton’s belief in architecture as both art and emotional infrastructure never wavered. Whether defending a crumbling landmark or championing a bold new design, she saw buildings as repositories of memory and imagination.

Patron Saint of Los Angeles Architecture

Keaton didn’t just advocate for preservation, she practiced it. Her homes were essays in adaptive reuse and architectural storytelling. She restored multiple Lloyd Wright properties, turned derelict Spanish Colonial houses into glowing showcases of California romanticism, and in her later years designed The House That Pinterest Built, a brick-clad ode to craft and curation that became the subject of her 2017 book of the same name.

Through her publishing collaborations with Rizzoli—House (2012), The House That Pinterest Built (2017), California Romantica (2019)—Keaton celebrated the patina and imperfection of California’s architectural vernacular. The books blended design documentation with autobiography, offering a view of Keaton’s mind as both archivist and artist.

For Keaton, preservation was inseparable from sustainability. “We’ve treated old buildings like we once treated plastic shopping bags—we haven’t reused them, and when we’ve finished with them, we’ve tossed them out,” Keaton wrote in a Los Angeles Times editorial. “This has to stop. Preservation must stand alongside conservation as an equal force in the sustainability game.”

That ethos guided her decades-long involvement not only with the L.A. Conservancy but also with the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Ennis House Foundation. Her aesthetic, minimal yet idiosyncratic, extended to her design collaborations, including a line with Hudson Grace that distilled her sensibility into objects: black-and-white tableware with stark architectural lines, clean and precise with a wink of eccentricity.

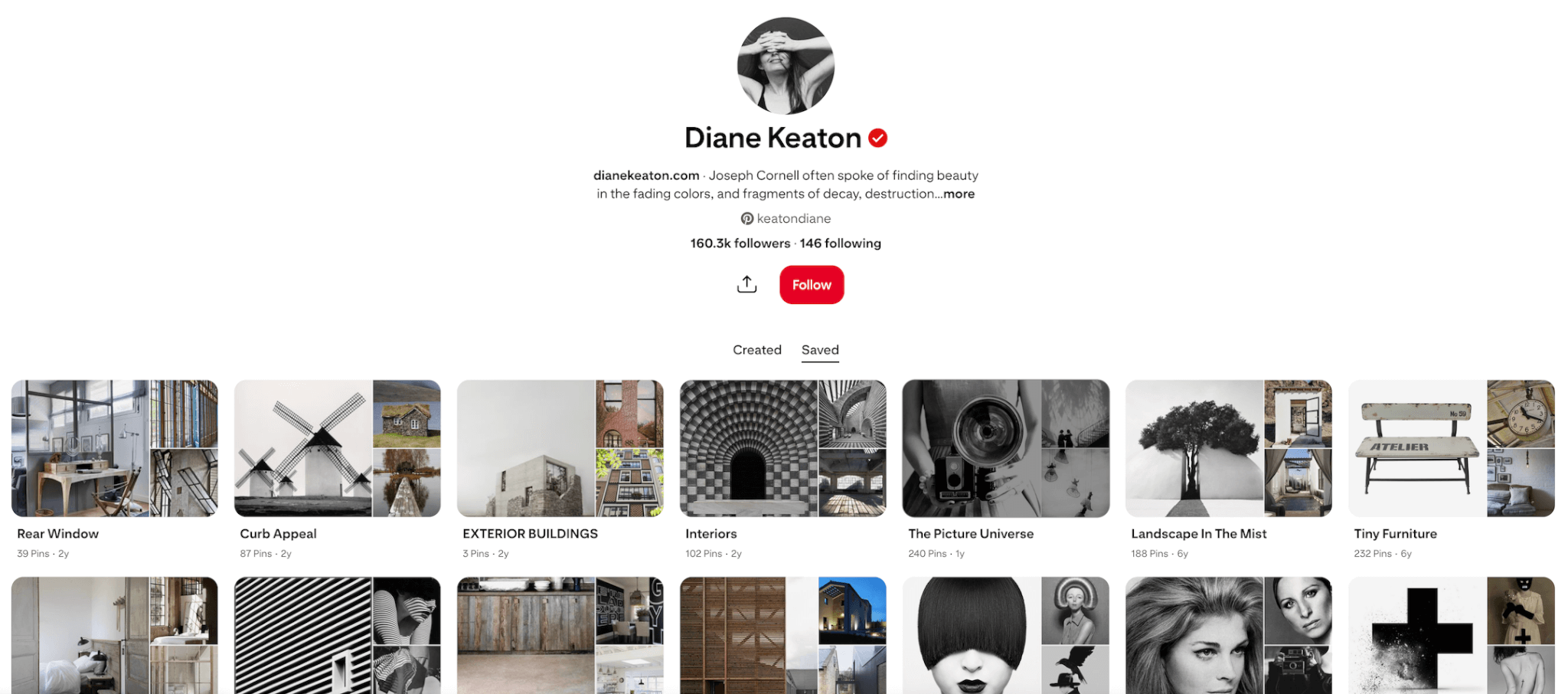

Even in her final years, Keaton’s curiosity endured. Her Pinterest boards which include thousands of images of facades, staircases, and light-filled interiors functioned as both research and reflection, a digital scrapbook echoing the collages her mother once kept.

“The more I got to know her, the more I understood where that passion came from,” former L.A. Conservancy president Linda Dishman told Variety. “A lot of that came from her family and growing up in Los Angeles. Really having a connection to the stories and places that make L.A. the city that it is. She had a very genuine passion for historic preservation, not only for the buildings or the cultural landscapes, but for what they mean to people and what they would mean in the future. She definitely got the relationship with how we’re doing this for future generations.”

She is survived by her two adopted children, Dexter and Duke Keaton.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper