Preservation in 2025 unfolded through petitions, landmark votes, courtroom drama, eleventh-hour real estate deals, and open questions about who cities are actually built for. From Brutalist city halls to desert art compounds and precarious midcentury homes, these stories were just as much about saving objects, as they were about stewardship, civic responsibility, and the uncomfortable cost of neglect. Together, they sketch a year when preservation felt like a referendum of public values.

Boston City Hall became a landmark

Few buildings inspire as much reflexive disdain, and stubborn affection, as Boston City Hall. Long maligned as harsh and unwelcoming, the 1968 Brutalist behemoth by Kallann, McKinnell & Knowles finally received official landmark status this year, after more than a decade of advocacy and near-demolition experiences during earlier plans to sell it off.

The designation does more than protect the poured concrete, it affirms midcentury civic architecture as worthy of care. Mayor Michelle Wu framed the move as an act of democratic stewardship, emphasizing adaptation without erasure. After years of deferred maintenance and aesthetic scorn, Boston City Hall is no longer a problem to solve–it’s a responsibility to uphold.

The ongoing fight for Dallas City Hall

If Boston’s City Hall marked a win, Dallas’s exposed the stakes. I. M. Pei’s inverted-pyramid City Hall became the center of a heated debate over repair versus demolition, public space versus redevelopment, and memory versus expediency.

Supporters frame the building as a rare civic gesture, monumental yet public, while opponents cite its ballooning repair costs after decades of neglect. The irony is hard to miss: the price of preservation has inflated precisely because the building has been ignored. As petitions circulated and landmark protection advances, Dallas City Hall emerges as a litmus test for whether American cities can still imagine civic architecture as something other than disposable infrastructure.

When an art school died, its buildings didn’t

When the University of the Arts in Philadelphia shuttered and nine historic campus buildings went to auction, Scout, a Philadelphia-based developer stepped in to acquire two: Dorrance Hamilton Hall built in 1826 and Frank Furness’s Victorian residence hall. Rather than rushing redevelopment, Scout marked the moment with a “Celebration of Life,” inviting former students and faculty back for performances, memory work, and collective mourning. The move framed preservation as tending to the cultural ecosystems they once held. With leftover studios, kilns, and dorm rooms slated for reuse as artist spaces and housing, the project suggests a model of preservation rooted in community.

Donald Judd’s built world got its due in Marfa

The long-shuttered Architecture Office of Donald Judd finally reopened in downtown Marfa, newly restored by Schaum Architects after years of planning, a devastating fire, and painstaking reconstruction. More than a house museum, the project made visible Judd’s self-described role as an “uncertified but active architect,” revealing drawings, models, furniture, and spatial ideas that were always central in his practice.

The reopening landed alongside the National Park Service’s addition of the Donald Judd Historic District to the National Register of Historic Places. The designation covers 15 buildings and one artwork across Marfa, including Judd’s adaptive reuse of the former Fort D. A. Russell, where military infrastructure became permanent, site-specific art. It formalizes what Marfa has long embodied, that Judd’s work was as much about buildings, land, and systems as it was about objects.

Victor Lundy’s House was saved by the right buyers

East of Marfa, in Bellaire, Texas, preservation came down to fierce advocacy and luck. Victor Lundy’s late career house and studio, a modest but luminous expression of his modernist ethos, was days away from deconstruction when it was quietly purchased by preservation-minded buyers.

The rescue was personal. Advocacy groups sounded the alarm, but the save ultimately depended on private stewards willing to treat the house as a living structure rather than a museum piece. The episode underscored a recurring theme of 2025: landmark laws don’t often consider modernist architecture, leaving survival to informal coalitions and goodwill.

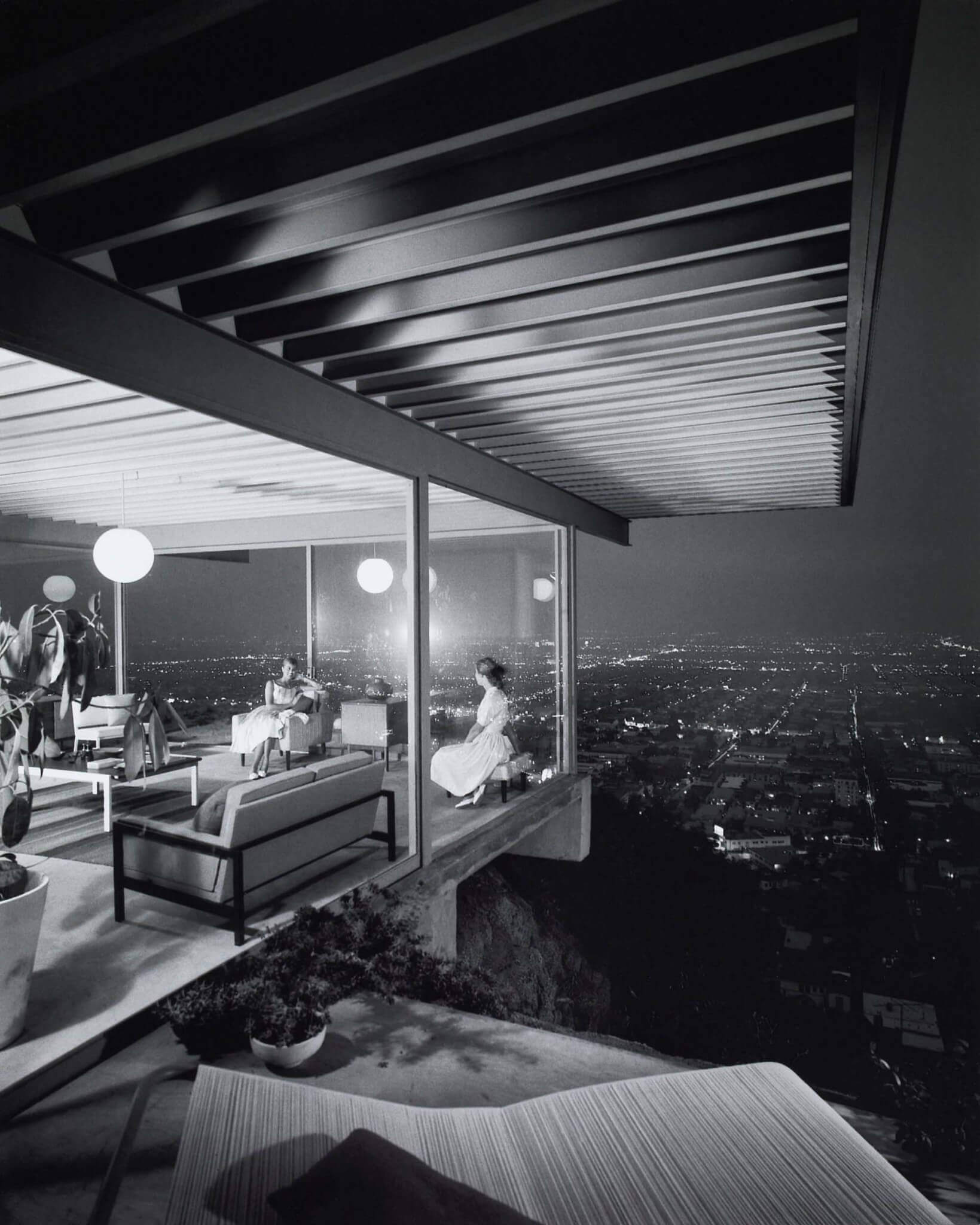

The Stahl House went on the market

Case Study House No. 22, the Stahl House, designed by Pierre Koenig and immortalized in a 1960 photograph by Julius Shulman, went on the market for the first time since it was completed. The Hollywood Hills residence has become one of the most recognizable works of midcentury modernism, its image synonymous with Los Angeles itself. The listing, handled by The Agency, is for $25 million, according to Zillow.

Situated on a dramatic cliffside site that other architects shied away from, the steel-and-glass house exemplifies Koenig’s belief in the hillside as an asset rather than a constraint. Floor-to-ceiling glazing wraps the living spaces, opening onto a pool that seems to hover above the city, while a cantilevered roof forms a carport. As a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument and the only Case Study House to remain in original family ownership, the hope, voiced by preservationists, is continuity and new owners who understand that the house belongs as much to the public imagination as to a deed.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Price Tower changed hands again

No preservation story in 2025 was messier than that of the Price Tower. Frank Lloyd Wright’s only built skyscrapers endured lawsuits, bankruptcy filings, sold-off furnishings, and the shuttering of its museum before landing with new owners promising restorations.

The tower’s saga revealed the limits of landmark status without financial stability. Preservation easements protected the structure, but not the institution meant to care for it. The hopeful turn came with new plans for a hotel, residences, and a museum anchored in Wright’s original interiors.

The Waldorf Astoria reopened

After a decade-long restoration by SOM, the Waldorf Astoria returned not as a replica, but as a carefully rebalanced organism. Art deco grandeur was restored, lost details reconstructed, and new uses layered in without collapsing the building into nostalgia.

The project offered a counterpoint to the year’s emergency saves and near-losses. Here, preservation was patient, capital-intensive, and deliberate. The Waldorf didn’t need rescuing because it was never abandoned.

Preservation this year was not about sentimentality. It was about maintenance budgets, governance failures, real estate pressure, and the uneven ways value is assigned over time.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper