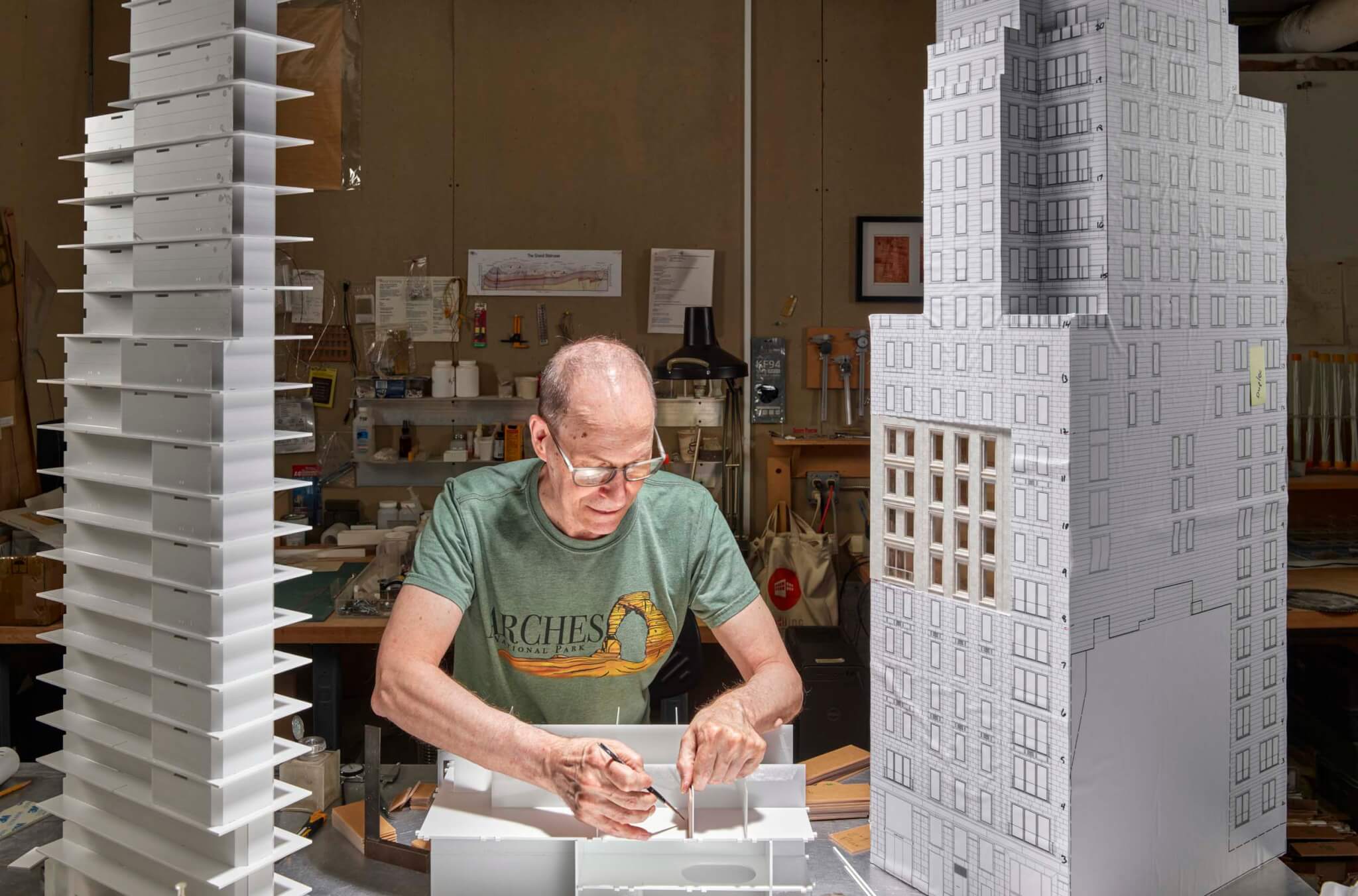

Recently, I stood in the conference room at Radii, a fabrication studio in Hoboken, New Jersey, peering at a packed shelf of architectural models. “You’ll probably recognize some of these,” Ed Wood, Radii’s director and founding partner, said to me. He was right. The tiny corner studies read like a who’s who list of contemporary architecture. “This is 11 Hoyt for Jeanne Gang. This one is 130 William for David Adjaye. This one is Lantern House for Thomas Heatherwick,” he continued. They are remarkably detailed and realistic, right down to millimeter-wide chalky gray bricks on Lantern House, or the bronze latticework on the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s facade, which resembles filigree jewelry at small scale.

Amid all of the ways to make an architectural model today—from 3D renderings to virtual reality fly-throughs and AI illustrations—there’s agreement at the upper echelons of architects and developers that there is no substitute for the tangible, physical thing. A cohort of model makers like Radii, which is celebrating its 25th anniversary this year, are continuing to push the art and craft of architectural models into exciting new territory. They’re theatrical pieces with iPad-controlled lighting, kinetic elements that reveal themselves with a push of a button, and, perhaps paradoxically for a scale model, the ability to become quite large. Radii made a 16-foot-tall model for SHoP Architects’ Steinway tower, which required cutting a hole in the sales office walls for it to be displayed. (A supertall tower deserves a supertall model, naturally.) When delivering a model to One World Trade Center, Radii had to transport it on top of the elevator cab to accommodate its height. Budgets can hit over $1,000,000. No, all those zeros are not a typo; the business of tiny architecture is indeed that big. But surprisingly, it still remains a little-known part of the architecture world.

Physical model-making has been an element of architecture since ancient times, but as digital tools like AutoCAD, Grasshopper, and Midjourney have come onto the scene, the role of the model has shifted. Sure, there are Richard Meier–like ateliers that churn out mini monuments to projects (though he might be the only one to build a museum to contain them) and designers who treat their models like sculpture. The interior designer Giancarlo Valle, who makes his models out of clay loofahs and wood, received a T magazine feature that lauded his “dollhouse like” maquettes. Most architects will have to slog through foam and cardboard in a studio at some point, but once they enter the professional world their work will happen entirely on a screen.

Now, however, some architecture firms are reinvesting in physical models. BIG recently quadrupled the size of its model shop in Brooklyn, to 3,500 square feet, due to increased demand for them. The firm has the same equipment as specialty shops: filament and resin 3D printing with large format capabilities, laser cutting, 3-axis CNC milling, and traditional shop tools. There’s a separate woodworking space and dedicated area for resin, plaster, and concrete casting. Meanwhile, the nomenclature is shifting too. SHoP, whose in-house models are highly regarded, calls its version a “Fabrication Lab.”

Why a Model Shop Can Pay Dividends

According to model makers, the investment is a smart move. “The good architects build models for themselves to iterate, to figure out what they’re designing, to catch problems early on,” said Jenny Tommos, an industrial designer turned model maker who once ran the model shops at Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Beyer Blinder Belle, and FXCollaborative, and currently runs the shop at WXY. “There’s a learning step translated into a model. The big, good architecture firms understand this. You can sort of tell when buildings are realized and you see stuff that actually wasn’t intentional—not that anyone’s going to own up to it at that point.”

At Rockwell Group, model making is frequently for internal use. “Clients rarely ask us for models, but we create them proactively because they tend to reveal things that renderings can’t—and bring the project to life,” said Brad Zuger, a Rockwell Group partner and studio leader. The firm also has a specialty practice making diorama-like models for theatrical productions, which directors, choreographers, and actors reference throughout rehearsal; the Victoria & Albert Museum acquired a few of these last year.

Firms that do have the resources and space for a dedicated model shop often use it for design and conceptual models and enlist hired guns when the stakes are high, like competition entries and donor gifts. Snøhetta, which has long centered models in its practice, commissions Radii when it needs a model “made in a more Sunday attire manner,” said Donesh Ferdowsi, architectural designer in the firm’s New York office, who works closely with the model shop manager, Mario Mohan. One of their recent collaborations was a gift for a panel reviewing a competition entry that consisted of a kit of parts that snapped together and was based on a conceptual model for the project. “That’s an instance where you’re moving fast, you know what you want, you don’t have time, and you want it to be really attractive for people,” Ferdowsi said.

Vincent Appel, founder of the architecture firm Of Possible, which works primarily on single-family residential projects, makes models for internal use. He recently enlisted Carlos Castillo, founder of the two-year-old model shop Castillo Fab, to make a series of display models of past projects to keep in the studio for reference and to help the work stand out. “You’ve got to figure out a way to punch through that sort of homogenizing effect of our image culture,” Appel said. “That’s what the effort is here with Carlos.”

Part of what’s driving model making today and fueling one-upmanship in the details used to create the models—is the booming luxury real estate market. Developers commission models for their sales suites in order to woo prospective buyers. “In the last 15 years, 80 percent of our work is just high-end and residential towers around New York or Miami,” said Michael Kennedy, the founder of Kennedy Fabrications, a “scaled constructions” shop located in Midtown Manhattan. (The other 20 percent of work at the studio has included installations for the set designer Es Devlin and a model of a railway station that appeared as a prop in HBO’s The Gilded Age.) “But it gives us an opportunity to make really museum-quality pieces, which I like.”

Those works have included a 9-foot-tall model for the Residences at the Waldorf Astoria, which took nine months to build and cost nearly $1 million. The six-figure price tag went toward gold leaf detailing, a mechanized roof that opens to reveal the amenity floor’s pool and winter garden, and over 4,000 lights inside that are programmed to illuminate individual condos. The model rests on a glowing alabaster plinth. While these elements inspire wonder in the people who behold the models, they’re also a mark of pride for the makers behind them. For a sales suite model for One Wall Street, a luxury apartment building, the firm made thousands of tiny vegetables for the basement grocery store, each so realistic you’d think you could bite into one. “That’s just obsession, honestly,” Kennedy said. “No one asked us to do those vegetables.”

A Profession for Architects, Craftsmen, and Dreamers

While methodical megadevelopment models may pay the bills, model makers sometimes prefer less glamorous formats. Tommos primarily works on sketch models, with “down and dirty materials: foam core and paper versus acrylic,” she says. “To me, they’re a lot more fun.”

Richard Tenguerian, a master model maker based in Noho, thrives on the fast-paced nature of architecture competitions. “The design is still cooking; it’s not complete,” said Tenguerian, who opened his shop in 1985. “I have my record—all the competitions that I build models for, they win. And we have never missed a deadline.” In these projects, there aren’t months to belabor tiny carrots, but there is the opportunity to work closely, and more collaboratively, with architects. For Tenguerian, who studied architecture at Pratt, model making has enabled him to work with numerous great projects instead of toiling away for years on the same building in an architecture firm. In his office, he displays a wall of busts of his clients, including Robert A. M. Stern, Thom Mayne, and Philip Johnson, all covered in plastic bags to protect them from dust in the shop.

But of all the models he’s built—including the 3-story-tall model of the Empire State Building in its lobby—Tenguerian is most proud of one for a Seattle tower by KPF where every single line is straight and true. The model is likely more perfectly aligned than the building. Tenguerian credits the precision to his training in traditional handmade techniques and hand cut and assembled all of the acrylic. Today he uses 3D printing, laser cutting, and CNC milling in his models, but he prefers to teach his employees—there are 16 in the shop—traditional methods too so that they work the same way he does. “ I don’t get ‘ready’ model makers,” he said, noting that someone who is set in their ways will have conflicts with how he likes to build. “[Model making] is very personal to me. I put my love into it.”

While the city’s top shops are run by people who have architectural training, it isn’t required to make a good model (though it certainly helps). Decades ago, Rafael Viñoly’s office hired Japanese cabinetmakers to craft its models. At Radii, a tattoo artist heads up the painting division, which is responsible for the intricate color-matched bricks all the way to creating naturalistic foliage on trees. (The secret recipe? Painting furniture foam, blending it in a coffee grinder, and repeating the process until it looks something like dried herbs.)

It’s also rare for architectural model makers to have specific formal model-making training since there isn’t a degree program in the U.S. for the specialty. In that regard, Adrian Davies, head of the model shop in NBBJ’s New York office, is a rarity. He graduated from the University of Sunderland, in the north of England, one of three colleges in the United Kingdom that offered a degree program in model making at the time. While he originally got into the field to work on visual effects in films, the shift to computer-generated imagery led him to architecture. “I always liked building things, but building buildings—that seemed good,” he explained. Castillo was self-directed, too. He studied architecture at Southern Polytechnic University and focused all his energy in studio on physical models, neglecting the renderings and floorplans, which were also part of the assignment. “I might not show up with anything else, but there’s going to be a badass model,” Castillo said. “I got away with that for a while, but not always.”

The training gap poses a challenge for the field. It’s hard for studios to come by people with shop and hand skills plus knowledge of design that makes models sing. This has had an effect on what the models look like, noted Jonathan Zack, a model maker and the shop manager for Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates. He’s noticed that as 3D printing has become more common, models have become sized to their printer beds. “We don’t use laser cutters and such machinery in our models but rely almost exclusively on hand cutting and hand assembling what are often very large-scale pieces,” Zack said, noting that project teams make their own models and he serves as the shop’s “lifeguard & cheerleader.” A model for Brooklyn Bridge Park was 65 feet long.

Manual Versus Digital

Some model makers are pushing to get architects comfortable working with their hands, in addition to digital tools. “What we’re trying to do at NBBJ is break them out of the computer and get them back into thinking by making,” Davies said. “Project managers like 3D printers because they don’t fill in timesheets. But if you need that thing quickly, you need the immediacy of hand tools.”

For the past few years, Davies has seen more architecture students with strong digital and physical model making work in their portfolio and in graduate exhibitions. “They want to do something a bit more real and are actually pushing back now from screens,” Davies noted. “I used to think until fairly recently the biggest danger for model making was not the lack of work, but the lack of people to do it. But we are actually seeing that there are people who want to do this.”

Ferdowsi, however, has had the opposite experience with the students he teaches at Parsons. “What I witness at the moment is an extreme poverty of embodiment,” he said. “It’s like they’re clumsy with their hands in a way that’s strange. I’ve had a class where I just brought in a bag of sticks that I collected in the park, passed out knives, and said, ‘Over the next hour, we’re going to listen to classical music and carve sticks.’ And it’s because they had zero control over tools. I was like, ‘Guys, you are going to be making the physical world and you have no way to participate in it.’”

Wood echoed the sentiment. “Because of liability and insurance, schools are reluctant to have power tools and table saws in their studios,” he said. Shop space is usually limited to digital and 3D printing because it’s safe. And I think the same thing is for architects’ offices.” Radii has had to develop a robust internship program to train architectural model makers, who usually stay with the studio for the long haul. John Shimkus, the project director at Radii, joined right out of Cooper Union and has been there for over 20 years. (Part of the reason for this is that the shop usually maintains a nine-to-five schedule so that its employees can have work–life balance, which is still not the norm in architecture.)

The overlapping Venn diagram of physical model making, digital fabrication, and architectural expertise is where Radii finds itself. While Wood and his since-retired cofounder Leszek Stefanski began with a mission to make one good model at a time, the studio now employs 12 full-time master model makers and has three to four large-scale projects in production at a time. It also has enough wiggle room to fit in a quick turnaround project, like a competition model where the challenge is “how few lines do you need to describe the spirit of a project with a short attention span of the jury,” Wood said. It has also steadily expanded to 8,000 square feet, with portions of the shop dedicated to painting, traditional power tools, a fleet of laser cutters and 3D printers, and electronics. It also has a photo studio in-house. Having everything under one roof lets the model makers control the quality and schedule much more tightly. “Whenever we rely on an outside source, it usually bites us in the butt,” Wood said.

Engineering to Rival Actual Buildings

While architectural drawings might be enough to build a real-world building, it isn’t a one-to-one translation for the model world. A lot of the work Wood and his team does is redrawing what they receive so that they can figure out how to make something that looks realistic, won’t fall apart, and, in the case of models with electronics and lights, can be serviced. And just as the built world around us has changed with the introduction of digital tools, so, too, has the model-making world changed. Traditional techniques alone can’t yield the complex forms architects gravitate toward. “The blob shape can be built in the real world, whereas 20 years ago, flat-plane towers were the norm,” Wood explained. “We no longer could just rely on flat laser-cut sheets of material. We had to evolve as architecture evolved. You can’t say, ‘Sorry, we can’t make that shape; call us when you’ve got a flat-sided tower.’”

The amount of engineering and thinking that goes into making these models might rival those of an actual building. “It’s a very similar challenge design-wise,” Wood said. “What’s the narrative? What story are we telling? What does the building look like? Is it transparent? Is it reflective? Is it bony? Is it smooth? It’s all the things on the creative end of making architecture and then making architecture small. It sounds really lofty for an architectural model, but it’s stuff we think about, and I think it’s what makes us unique.”

Wood handed me a 6-inch-square study model for a model (they make study models just like architects do) of the KieranTimberlake-designed U.S. embassy in London, which has an undulating, translucent ETFE scrim affixed to the facade. Making a miniature version involved laser-cutting the back face; creating a Corian mold that they then used to Vac-U-Form acrylic to the shape of the scrim; etching metal to mimic the armature that holds the scrim; and applying extremely thin layers of glue to adhere the structure to the scrim, all while maintaining the exact proportions of the real building. “We’re thinking down to the 5,000th of an inch,” Wood said. For 130 William Street, Adjaye’s residential 66-story tower clad in tinted concrete, Radii opted to build a model from walnut, as opposed to painted acrylic, to evoke the facade’s richness. “It’s like a grandfather clock,” Wood said. “It’ll be an heirloom that will last forever.”

The effort is worth it in the end. Models get results. Zack recalled assembling a multiblock cityscape as a client observed. “She reached into the model, picked up a miniature city bus, and pretended to drive it around the streets,” he explained. “She said, ‘This is the doll’s house my father never let me have’ and approved the entire project. I’m not so sure that would have happened with a few renderings hanging off the wall.” Davies remembered a similar experience. The decision-makers involved in Massachusetts General Hospital weren’t able to grasp design proposals presented in renderings and video fly-throughs, so the team made a model and presented it in person. “We get there, we put the model down on the conference room table, the client takes one look and said, ‘Yes, that’s it,’” Davies said. “Everyone thinks models are a magical thing, but I think actually it’s the clarity that they give that [makes them special].”

Models are more legible for everyone than a two-dimensional image, which is especially critical for long-term, multiphase projects. They’re “the best way to communicate a substantial and often yearslong vision, helping our community see the components of a project and how it all knits together,” said Dave Lombino, managing director of external affairs at Two Trees, the developer behind the transformation of the Williamsburg waterfront around the former Domino Sugar Refinery into a mixed-use neighborhood. Two Trees hired Radii to make the model, which sits in the lobby of the Refinery at Domino, an office building at the heart of the redevelopment. “Each building on the Domino site is architecturally distinct, so we appreciated Radii’s unmatched attention to detail,” Lombino said.

Ferdowsi notes that models also help with internal decision-making at Snøhetta. “Models are a really important social tool,” he said. “Because we’re a very collaborative design studio where ideas come from every level, the challenge is actually to develop a coherent collective voice.”

Through the years, WXY’s Tommos has noticed more architecture firms opening their model shops to the entire staff, Snøhetta style, which she fully endorses. “Sometimes people ask me, ‘Oh, but if architects build their models, won’t you be unemployed?’” she said. “And I cackle, because I won’t be. I teach people, more than anything. I build, too, but the bigger role is to help inform and strategize around models.” Right now, there’s more work than there are people who are capable of doing it, especially for freelancers. “I literally can’t find people that have skills,” she said. “It’s a problem.”

To help increase the visibility of architectural model makers in New York, and perhaps attract more people to the field, Tommos launched the Model Makers Guild of New York, a first-of-its-kind group in the city. (There is a national model-making organization, the Association of Professional Model Makers, but it’s ceasing operation at the end of the year.) Tommos’s group is an email list and forum that helps the makers build community, trade notes on technical questions, and find work. Tommos also organizes visits to model shops across the city. “It’s not to our benefit that we’re sort of hidden,” she said.

Despite working on many high-profile projects through the years, Radii sometimes experiences a similar challenge. “We have to continue to reintroduce ourselves and be discovered again,” Wood said. “We go through cycles of turnover of staff studios that we have close ties with during recessions.” Additionally, big firms have been commissioning models from overseas shops when their clients aren’t willing to pay the price for a high-quality model. There’s a global market that didn’t exist a decade ago. “There’s a large, government-sponsored model-making factory in China that can make a ‘fast food’ model for about a third of the cost of what can be done the right way in New York,” Wood said. “Our reward is when we get a call three months later: ‘The model has arrived in pieces. Can you make it look good?’ Or: ‘The model arrived, and we can’t use it.’ I resist saying ‘I told you so.’” Regardless of these industry changes, Wood isn’t reactive. “We just maintain the highest level of quality and service and never miss a deadline,” he said. “We’re riding on that reputation.”

Fans of model making are eager to share their enthusiasm and hope more people join them in their appreciation. “When you encounter a model, there’s a sense of delight, of love, of attraction, magnetism,” Ferdowsi said. “And I think the world is becoming increasingly thirsty for some semblance of realness. The tricky thing is you can’t be hungry for something you’ve never tasted.”

Diana Budds is a design journalist based in Brooklyn, New York.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper