Bad Bunny’s performance at Levi’s Stadium on February 8 garnered close to 130 million live viewers, per data from Nielsen, denoting one of the most-watched halftime shows in Super Bowl history. The 13-minute set in Santa Clara, California, by Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio was ideated by creative director Harriet Cuddeford, designers at Yellow Studio, and stylist Karla Miranda. Bad Bunny’s best friend Jan Oliveras was also a collaborator.

The elaborate ensemble had 9,852 theatrical pyrotechnic devices, over 300 performers, and another 383 extras dressed as grass, revolving like clockwork before La Casita, an immersive stage modeled after the home of Román Carrasco Delgado—an 84-year-old Puerto Rican resident—in the coastal town of Humacao. Delgado designed and built the home with salmon pink walls and yellow trim for he and his late wife, later reconstructed by Bad Bunny’s team.

Delgado’s home initially featured in Bad Bunny’s short film Debí Tirar Más Fotos which lamented gentrification in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. After the short film’s release, the home has become popular with fans, maybe a little too popular. The homeowner Delgado has since sued Bad Bunny and three companies—Rimas Entertainment, Move Concerts PR, and A1 Productions—for $1 million in “damages and emotional distress” over “illicit enrichment” allegations.

Extras draped in tall shrubs native to Puerto Rico coalesced around laborers toiling in staged sugar cane fields during the performance. Auditions were held in Puerto Rico to dress as the “bush people,” and producers received over 40,000 applications for the select amount of coveted gigs. Electrical poles Bad Bunny climbed were a nod to El Apagón (The Power Outage), directed by Kacho Lopez Mari with reporting by journalist Bianca Graulau, which critiqued LUMA Energy, the private company that controls Puerto Rico’s grid.

“As a Puerto Rican designer, I saw the halftime show as a spatial narrative, an ode to the lived reality of Puerto Rico: not idealized, but honest,” said Isabel Lopez Font, an interiors architect at NAINOA, and based in San Juan. “Through symbolism and set design, it carried history while balancing references to our social and political tensions with a strong sense of unity, showing how cultural expression can transform struggle into collective celebration through space and performance.”

Diasporic Mobilization

The Caribbean Social Club’s storefront in South Williamsburg, Brooklyn, was reconstructed as part of the performance; its proprietor Maria Antonia “Toñita” Cay served Bad Bunny a shot. A couple from Puerto Rico held their actual wedding on stage, and kissed. Bad Bunny handed a little boy a Grammy’s Award. Other motifs sourced from Puerto Rico were also weaved throughout the segment, and stars like Pedro Pascal, Cardi B, Ricky Martin, Karol G, and Lady Gaga had cameos.

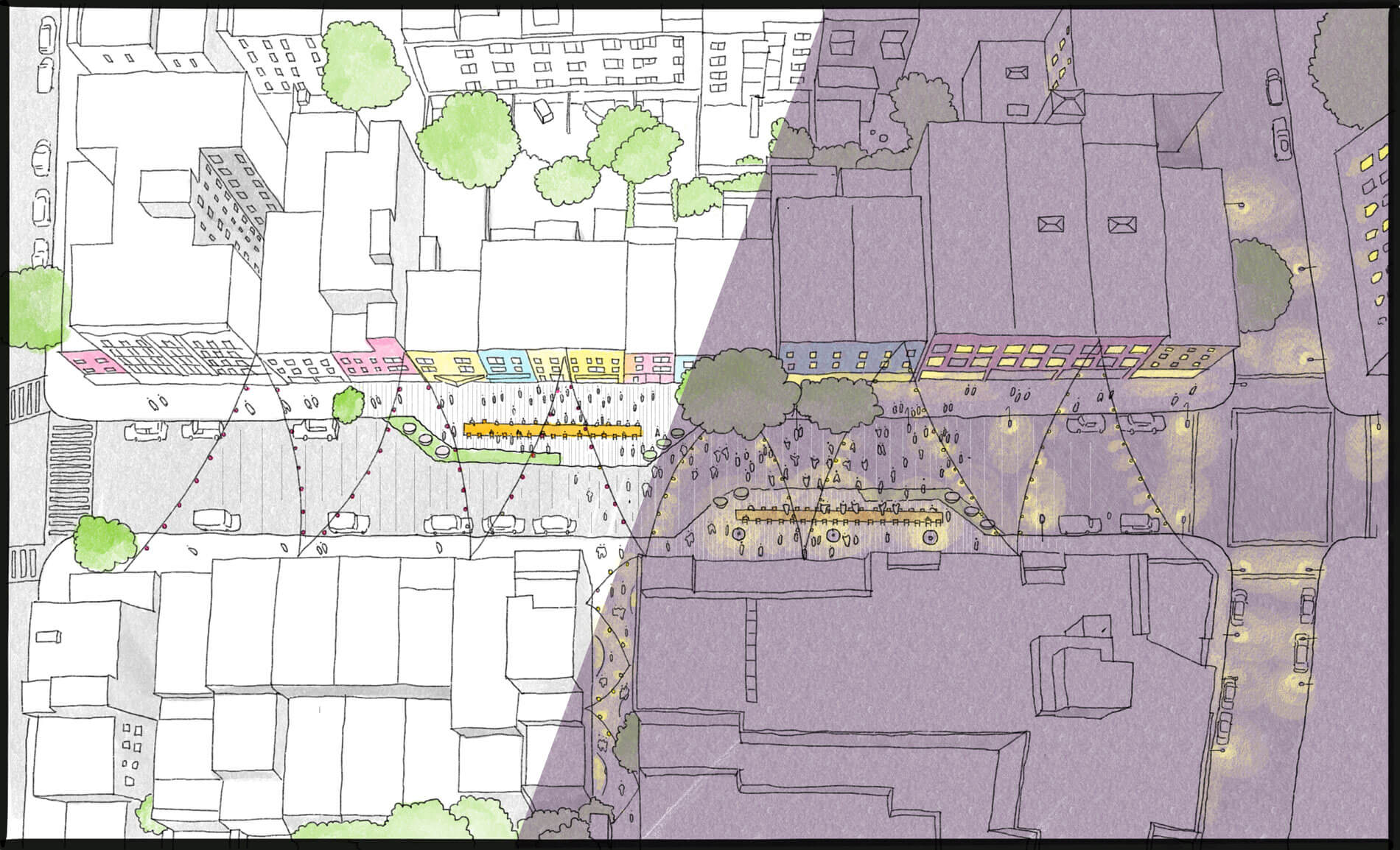

Marvel partner Annya Ramírez-Jiménez worked with the Caribbean Social Club as part of the COVID Memorial Project which sought to help distressed small businesses during the pandemic. Ramírez-Jiménez and designers at Marvel collaborated with Cay on an unbuilt, conceptual urban design project to reimagine the street outside the Caribbean Social Club as the “Caribbean Social Block,” which would have brought chairs and communal tables outdoors, extending the club into the urban fabric.

“Rather than designing a static monument, we chose to monumentalize the block party itself: a long communal table that invites people to arrive fully and be affirmed as part of a collective,” Ramírez-Jiménez told AN, in regard to the collaboration with Caribbean Social Club.

“Puerto Rican identity operates as a template for transnational belonging within U.S. geographies,” she continued. “Through the symbols of the New York diaspora, Bad Bunny’s descent into a block party during Super Bowl halftime, framed by La Marqueta, the barbershop, and the Caribbean Social Club, he activates a spatial network that transforms foreign ground into community, warmth, and recognition of the ‘other.’”

To Ramírez-Jiménez’s point, aside from the Caribbean Social Club, more diasporic homages—Piragua stands, Lalo’s Barbershop, a bodega—were likewise incorporated. Nail artist Johana Castillo was seated at a round table offering a manicure. After the show, nail technicians in California applauded Bad Bunny for “putting nail tech culture on the biggest stage.”

“In the realm of architectural representation, the Super Bowl halftime show—however fraught as a capitalist platform and without romanticizing the spectacle—was strategically mobilized as a living anti-colonial collage,” Iowa State University professors Cruz Garcia and Nathalie Frankowski told AN. “We call this process the post-colonial method: to make visible the forces and infrastructures of colonialism.”

“To close with the marching flags of Abya Yala,” Garcia and Frankowski added, “from Haiti to Cuba to Venezuela, is to invoke a hemispheric need for networks of solidarity in the face of fascism and imperialism—a gesture that, as we argued in 2020, connects today’s loudreaders to the anti-colonial traveling performers of the tobacco factories of the early twentieth century.”

Indigenous Landscapes

Choreographing the set started in October, so the whole performance came together in just four months, Cuddeford recently told Dazed. “The taco guys were real taco guys from L.A. The nail girl was a real nail girl,” she said in regard to its authenticity. “The boxers were real boxers,” Cuddeford added, before noting, “we also had people in the sugarcane fields doing their real jobs.”

Marissa Angell, founder of Angell Landscape Architecture, unpacked the set design’s symbolism on social media. “The history of sugarcane in Puerto Rico is complex, fraught with exploitation, and deeply intertwined with the cultural roots of the island. It’s only fitting that this tall, tropical grass species plays a prominent role in Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime show,” Angell said on Instagram.

“Monoculture-esque rows of grasses evoke sweeping tracts of pastizales, or native grasslands, which can be found in a variety of permutations, from steep serpentine slopes with slender grama, or coastal shores featuring saltgrass,” Angell continued. “There is a deep sense of pride in these indigenous landscapes; many are imperiled through forces including development, climate change, and incursion of invasive Guinea Grass.”

Other Easter eggs Angell called attention to included accessories woven using Puerto Rican hat palm, or sabal causiarum. “Displayed behind surprise guest artist Ricky Martin were tall, proud stalks of Musa x paradisiaca, or plantanos,” Angell added. “Though not native, platanos are a staple and an important feature of Puerto Rican cuisine. In times of scarcity it was a respite from famine and was a primary food source for those enslaved on plantanal (plantations). Now, it is a symbol of resilience and hope in the face of adversity.”

Garcia and Frankowski had similar sentiments: “The performance traced a visual and symbolic arc from the brutality of the sugar plantation in Borikén, to the forced Puerto Rican diasporas of Nueva Yol, to the rebellious perreo of racialized and queer bodies, and finally to the denunciation of Puerto Rico’s crumbling electrical grid—a symptom of colonial austerity measures imposed under Obama’s Fiscal Control Board, established by PROMESA, cynically, the ‘Promise’ Act.”

Personal and Cultural Connections

Set design and architecture has long been integral to Bad Bunny’s artistry. Dominican-American photograpaher Renell Medrano collaborated with Bad Bunny last year on the NUEVAYoL music video, which featured a quinceañera inside Bronx Community College’s Meister Hall, designed by Marcel Breuer. The Statue of Liberty scene in NUEVAYoL by Medrano is an homage to a very real occupation that happened there on October 25, 1977, when Puerto Rican nationalists, led by Fernando Ponce Laspina, held court at the Statue of Liberty for eight hours to protest U.S. settler-colonialism.

Lopez Font told AN the more recent Super Bowl halftime show was “a visceral moment to witness as a Puerto Rican designer,” before affirming: “It reflected my own lived experience and the current social landscape with authenticity, creating a deep sense of personal and cultural connection. The set design translated cultural memory into built form through familiar textures, landscape references, and layered symbolism that acknowledged ongoing struggles while framing collective pride as an act of resilience.”

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper