New York 2020: Architecture and Urbanism at the Beginning of a New Century by Robert A. M. Stern, David Fishman, and Jacob Tilove | The Monacelli Press | $150

It is difficult to resist the temptation to locate your past lives within New York 2020: Architecture and Urbanism at the Beginning of a New Century, especially for those who lived in the city between September 11, 2001 and the onset of COVID—arguably one of the most intense periods of building activity and compressive change in New York’s history. These two decades encompassed extraordinary leaps as well as profound ruptures: civic trauma and memorialization; economic collapse and speculative recovery; technological acceleration, climatic catastrophe; and a steady erosion of professional, political, and institutional certainty. This final installment in the six-volume series, completed by Robert A. M. Stern (and published just before he passed away) with co-authors David Fishman and Jacob Tilove, presents an unexpected, obsessively detailed, intentionally depersonalized 10.5-pound encyclopedia of buildings—and of the events, barriers, and administrations that shaped them.

Rising Above

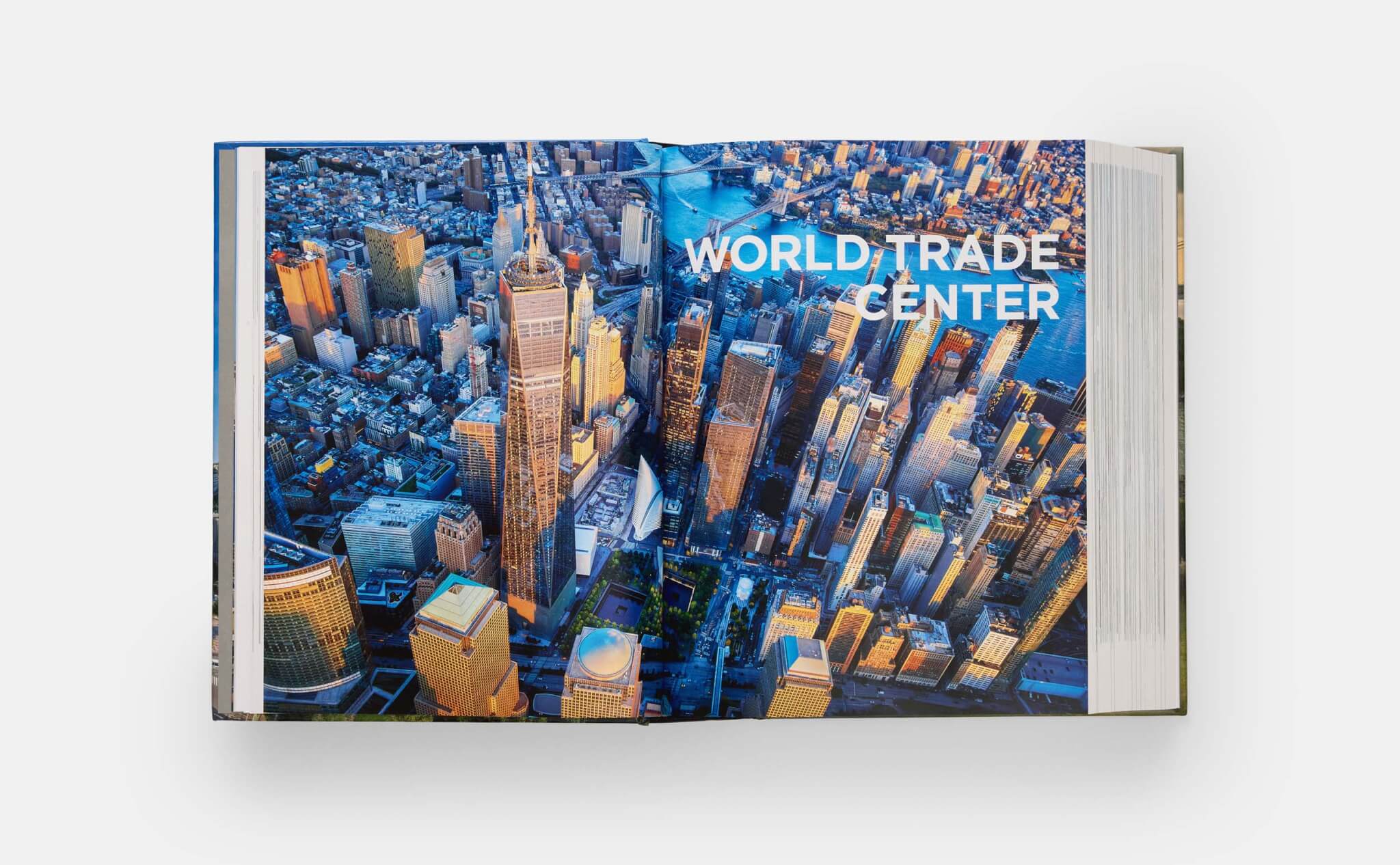

After the 90-page Introduction’s grounding, this 1,500-page mastiff documenting more than 3,000 projects across the five boroughs, leads, inevitably, with September 11, 2001 in “World Trade Center.” The event reset the city’s psychological baseline and reorganized its spatial, political, and security priorities while thrusting cultural memory and absence into public discourse. It examines in mythological detail, the Libeskind master plan, memorial competition, formation of the LMDC, completion of David Childs’s Freedom Tower, and the charged undertaking of building the National September 11 Memorial and Museum, its flanking towers, maintenance buildings, new PATH station and supporting sub-grade infrastructure concurrently. Much of New York 2020 is conveyed through the lens of “contemporary media.” The voices of professional critics, architects, and urbanists echo in familiar tones throughout, inspiring sometimes painful recollections, rearview catharsis in ten chapters rolled out by geography.

A period of extraordinary municipal confidence followed the post-9/11 environment under the Bloomberg administration, whose governance and wave of rezonings fundamentally reshaped the city’s physical and economic landscapes. Waterfronts were reimagined, former industrial districts were converted into high-density mixed-use zones, and public–private partnerships became the dominant mode of doing business. New York reasserted itself as a trend-setting global city in his 12-year run, attracting foreign capital at an unprecedented scale—while inadvertently accelerating inequality and displacement in ways architecture alone could not resolve. The book’s photographs, restrained in scale and largely confined to a two-column layout (with exceptions), thumbnail buildings and their champions all too well. Significant advances in digital design, visualization, and an increasingly virtualized attention economy made architecture more accessible. This period marks the emergence of “smart” buildings shaped by high performance, efficiency, and environmental responsiveness, conveying a distinction in the building stock and its connective tissue.

The 2008 global financial crisis arrested momentum after 9/11, exposing fragility beneath apparent prosperity as projects stalled and ambition adjusted—the result of a “nationwide burst of a housing bubble” that lasted through the second half of 2011. Development returned thereafter with intensity, increasingly shaped by global wealth, financial abstraction, and real estate as a hedge against market volatility. The city would continue to become taller and more polarized—nowhere more visibly than along Billionaires’ Row.

Few projects communicate renewal more clearly than the High Line. Conceived as adaptive reuse and a civic gesture, it became a global prototype for design-led urban regeneration. In New York 2020, the High Line reads less as a singular achievement than as a pivot point, marking the moment when design excellence became inseparable from accelerated development and value extraction. By the 2010s, financial abstraction found its most extreme expression in the rise of the supertall. Enabled by zoning loopholes, air-rights aggregation, and engineering innovation, these slender structures recast housing as a swaying global asset class. The skyline grew more dramatic as the social contract beneath thinned.

If finance reshaped the city vertically, Superstorm Sandy reoriented it horizontally—forcing climate vulnerability and infrastructural exposure into the mainstream. Neighborhoods flooded, transit systems failed, and 20th-century systems met 21st-century climate reality. Resilience planning moved from the margins to the center of architectural discourse, reframing practice as a form of adaptation. Remapping the floodplain introduced new pressures on building morphology and further destabilized the notion of a solid ground. This change continues to unlock opportunities for more resilient public space and sectional connectivity.

Private Versus Public

The Mayor de Blasio years attempted to counterbalance inequity through affordability. New York 2020 captures a persistent tension between progressive policy ambition and the mechanics of development. Architecture during this period navigates an increasingly constrained terrain—caught between public aspiration, private capital, and regulatory compromise. Running parallel to civic and economic shifts is a quieter but equally consequential narrative: the erosion of architectural agency itself. Even amid one of the largest building booms in the city’s history, the profession contended with fee compression, consolidation, design–build delivery and diminishing authorship. Starchitecture receded—not because spectacle disappeared, but because its cultural authority fractured.

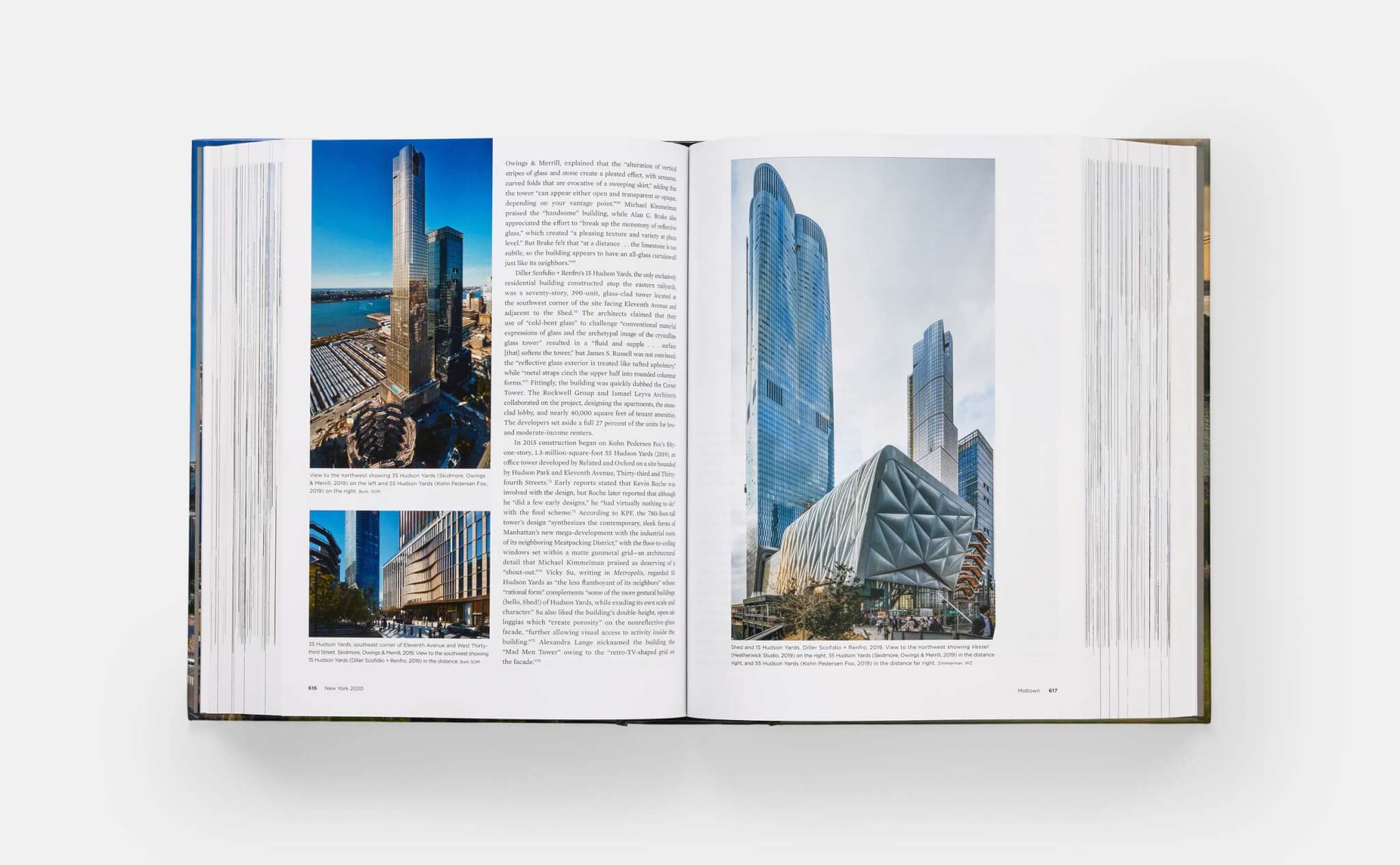

True to its editorial position, the book resists foregrounding individual authorship. Still, a constellation of architects represent the era: SHoP Architects, Renzo Piano Building Workshop, Ateliers Jean Nouvel, Zaha Hadid Architects, Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), Weiss/Manfredi, COOKFOX, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Snøhetta, KPF, Tod Williams Billie Tsien, FXCollaborative, Studio Gang, OMA, Grimshaw, Heatherwick Studio, SANAA, Morphosis, Gehry Partners, SOM, and Selldorf Architects, among others. Across their canon runs a shared recalibration: data-informed design, complex geometries, new structural and envelope logics, renewables, offsets, and deep entanglement with technology, policy, and delivery systems. Emerging minority and women-owned practices, architects-of-record, interdisciplinary collaborators, construction managers and trades people supporting the canon often ensured realization without recognition. What ultimately endures is not individual genius but an evolving collective intelligence: collaborative authorship increasingly oriented toward public space, environmental sensitivity, shared civic ground and a redistribution of risk.

The New Ecosystem

The book’s temporal arc closes with the arrival of COVID in March 2020—an event that emptied offices, halted construction, and called into question long-held assumptions about urban density and human proximity. Like September 11, the pandemic functions as another massive rupture with far-reaching implications.

New York 2020 reads as a comprehensive urban ledger. Its exhaustive “allness” reflects not only the scale of transformation over 20 years but also the contradictions that fueled it: commercial confidence paired with institutional fragility, spectacle coinciding with diminished agency, prosperity shadowed by loss. The volume unfortunately falters in its Afterword. After devoting most of its narrative weight to Manhattan and Brooklyn, the remaining boroughs’ treatment feels light, and the pandemic on some level receives only cursory treatment. One wishes for a fuller coda—an acknowledgment that COVID marked not an ending, but another inflection point responsible for reshaping the AEC, accelerating New York’s role as an inclusive technology and innovation hub, and redirecting investment toward the housing crisis, future-forward infrastructure and climate resilience. That this next phase remains unexamined feels like a missed opportunity though one must recognize that there is a 2020 cutoff. In this sense, New York 2020 stands as a reckoning—an inventory of a city propelled forward that is best visualized in Milton Glaser’s 2001 reworking of his famous 1975 advertising campaign: I Love NY More Than Ever. Bones and all.

Allan Horton is a Brooklyn-based architect and regular contributor to The Architect’s Newspaper.

This post contains affiliate links. AN may have a commission if you make a purchase through these links.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper