Since 2005, the Portland Art Museum has occupied two buildings: its original, thrice-expanded Pietro Belluschi structure and a converted Masonic temple by Fred Fritsch one block to the north, both linked by a tunnel. This was no grand I. M. Pei–style National Gallery concourse; rather, it was an overlooked corridor lit by artificial light that visitors hastily scurried through.

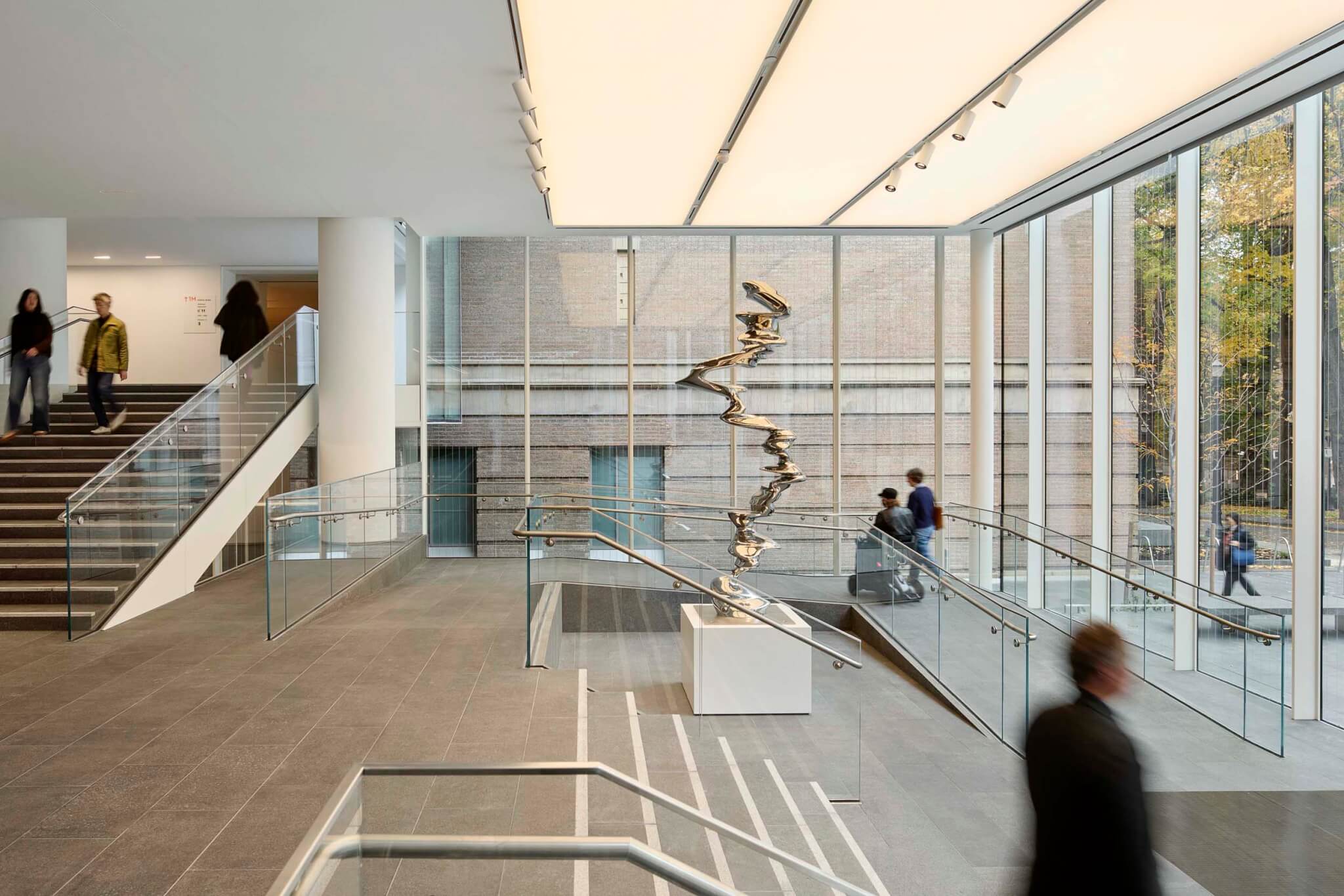

The museum has set out to change this with a new addition, the 21,881 square-foot Mark Rothko Pavilion designed in collaboration by Vinci Hamp Architects and Hennebery Eddy. Officially open to the public as of November 20, the expansion fills in the gap between the buildings, admirably knitting together its gallery spaces. They’ve also added on a new loading dock with a gallery above and repurposed a number of other spaces to bring the institution’s total square footage to nearly 100,000 square feet.

An Extended Welcome

Central to the design was the need to create accessibility and connectivity. The museum’s former director, Brian Ferriso, recalled in conversation with AN visiting the museum before he was hired and being warned a volunteer about the 1924 former Masonic Temple, subsequently known as the Mark Building, “Whatever you do, don’t go into the building because you’ll get lost.”

Tim Eddy, founding principal at Hennebery Eddy emphasized the same point, “You had to have a compass and a map to send somebody to the other part of the museum. A lot of people never made it over there and if they did, they didn’t know how to get back.” Masonic temples have never been known for their transparency. Its revamp for museum use by Ann Beha in 2005 introduced a single vertical pleat of windows, a commendable decision from a preservationist standpoint but one which left a rather dark space for viewing art.

For this addition, the architects chose glass for the material theme to provide visibility on the street-level and offer a contrast to the original masonry from the street level. Ferriso explained that passers-by were often unsure what was even inside the structure—it seemed inadequate for an art museum located in a vibrant downtown. Their resolve with the addition was as he explained, “to invite the city in” with a transparent volume that would connect the city’s west and east sides.

The existing pleat in the Mark Building provided clear logic for where to site the Rothko addition. Philip Hamp, president of Vinci Hamp explained, “That’s where we entered that building, mostly because we didn’t want to destroy any more of the facade.” Eddy continued, “Now when you’re standing in the North Wing you can see all the way almost to the end of the South Wing. That was the strong organizing element.”

A double-height space was carved out of the Mark Building just inside its link with the Rothko. On the other side, the Pavilion connects roughly at the junction point of the 1939 and 1969 Belluschi additions, enabling another circulatory fix. Ferriso explained, “The galleries in the [1969] Hoffman building [addition] were sort of sequestered. It was almost like you were going into a back alley. You’re now entering in a much more central way from the north-south corridor.”

Expanding on Belluschi’s Legacy

What is now known as the South Wing of the museum is an engrossing, block-spanning structure by Belluschi, the emigre engineer from Ancona, Italy, who would later become the foremost modernist of the Pacific Northwest. He designed the initial structure in 1932, after the death of his employer and the intended designer, Portland architect A. E. Doyle.

The museum was Belluschi’s first commission, but one in which he took a substantial turn toward the future. An initial neo-Georgian design offered a relatively easy opportunity to ford the stylistic river toward modernism, which he did by discarding the hipped roofs and trading the string courses and sash windows for ribbon windows. Bricks in Flemish bond from the local Willamina Clay Company and trim in travertine offer a material continuity with the design’s stylistic precedent.

Belluschi was never a modernist provocateur. Instead, his approach was that of a practical thinker, he argued in a 1931 memo to the chair of the museums building committee, “Let us not try to maim and twist the body to fit the suit but let us build a new suit consistent with the body.” One of his innovations was to implement monitor windows instead of the more popular skylight to shift illumination from the center of the galleries toward the walls containing art. He had support from a useful source. Frank Lloyd Wright wrote, “I think your plan simple and sensible and the exterior would mark an advance in culture for Portland.” The museum would become one of the first modern museums in the country, preceding MoMA by seven years.

Belluschi would prove a consistent steward to the building’s design across more than three decades. His first addition to his original 1932 design the Hirsch Wing, which doubled the museum gallery’s space and added a sculpture court. Then, in 1968, Belluschi was asked to construct an additional expansion, which would become the Hoffman Wing, which was completed in 1969 Here he acted with greater modern confidence, recessing a single strip of vertical windows on its western side and designing especially impressive fourth floor canted clerestories and skylights.

However the addition of the renovated Masonic temple in 2005 presented a counterpoint to Belluschi’s extended vision for the museum. With this new pavilion the architects were confronted a difficult task: the shotgun marriage of two elderly spouses. Hamp noted, “The Belluschi is kind of a streamlined Georgian and the Masonic Temple is almost movie palace architecture. You’ve got these two strong historic buildings that were never intended to be connected. How do we connect them and flatter both of those buildings?”

They’ve succeeded entirely at flattery. Volumetrically, the Rothko Pavilion is exceptionally polite, taking care to respect not only the Masonic temple but also the articulation of two different Belluschi portions with minimal alterations. And yet, deference can go too far; the Rothko Pavilion’s curtain wall does not provide all that great of an impression beyond channeling visitors from one building to another. It may be a tall order to compete with Belluschi, however a normal curtain wall can’t help but feel a bit wan next to his febrile work.

Form and Function

There is no question that the Portland Art Museum has been dramatically improved as a functional facility, however. The Rothko Pavilion elegantly addressed the plethora of obstacles and incongruities faced by the architects. Take, for example, the differing levels in the buildings (which ranged up to about a foot and a half), which were accommodated by a partial stair on the ground floor and slight ramps on other levels. Accessibility problems were resolved with two new elevators, one which is a defining glass-clad formal feature of the Pavilion and another that’s just inside the Belluschi volume. Siting these elevators was not easy due to existing underground infrastructure, including an auditorium retained from the 2005 iteration of the museum. Hamp compared it to “threading a needle.”

The site also presented its own challenges. The City of Portland remains justly possessive of its human-scaled downtown, which is composed of 200 feet by 200 feet blocks and objected to the formation of a superblock which would foil pedestrian access. The designers worked the pavilion over a pedestrian path accordingly. Touching down was as issue in other regards; the western facade is fairly flat but the sloping eastern side required ramps both inside and out to accomplish accessibility goals.

In spite of the constraints, the double-height second and third floor spaces of the Rothko Pavilion are genuinely very appealing, with diagonal dynamism wrought out of a kink in the mezzanine to link a column and the elevator bay. The knitting together of galleries makes for a very considerable number of ways to pass through ages both of art and architecture here.

With this expansion, the museum makes room for more art. The pavilion features a range of sculpture, glassworks, and ceramics from the likes of Alexander Calder and Tony Smith. Henry Moore and Barabara Hepworth pieces on an outdoor terrace offer a particularly impressive foreground for taking in the sum of these buildings. A new gallery will permanently display a rotation of the Pavilion’s namesake. Rothko, a Portland native, had his first exhibit here in 1933. Other notable Portland names like Carrie Mae Weems and Mark Tobey can be found nearby.

Currently on view at the Portland Art Museum there are also superb exhibits on lesser-known-but-great Pacific Northwest artist Mary Henry and Rick Bartow, and thoughtful surveys from diaspora artists who lived and worked on the West Coast. Notably, there is a refreshing meta-narrative look at the museum’s history of showing Native American art, which involves plenty of great art, especially by contemporary living artists, which offers a welcome contrast to the anthropological approach of many similar collections.

All of this becomes more accessible with the new addition and does fulfill, as it were, a Belluschi hope. In an interview from the early 1990s about the museum he mused, “I have a dream that they could enclose that part that is between the museum and the Masonic Temple and build wings.” They’ve done it, Pietro.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper