If you want to look into the heart of contemporary architecture today, you are going to need a REAL ID. You will have to pack your bags and find your way to Northwest Arkansas, a wrinkled, rugged stretch of land. The trip is not convenient, but you will have a good time. This is Razorback country, a region that has exploded with growth thanks to the success of its hometown corporation, which keeps the rest of the country running: 90 percent of Americans live within 10 miles of a Walmart. History here is still being written, with an expanding art museum and a new medical school, plus highways under construction, open gashes where rusty soil shouts against emerald fields.

It’s here, in Fayetteville, along a busy arterial street opposite a Walmart, where the Anthony Timberlands Center (ATC), a new building for the Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design at the University of Arkansas designed by Grafton Architects with modus studio, has risen like a roadside attraction or a wayside shrine. Those who visit and look closely may come away with a sense of a powerful—and benevolent—contemporary sensibility for how to make architecture.

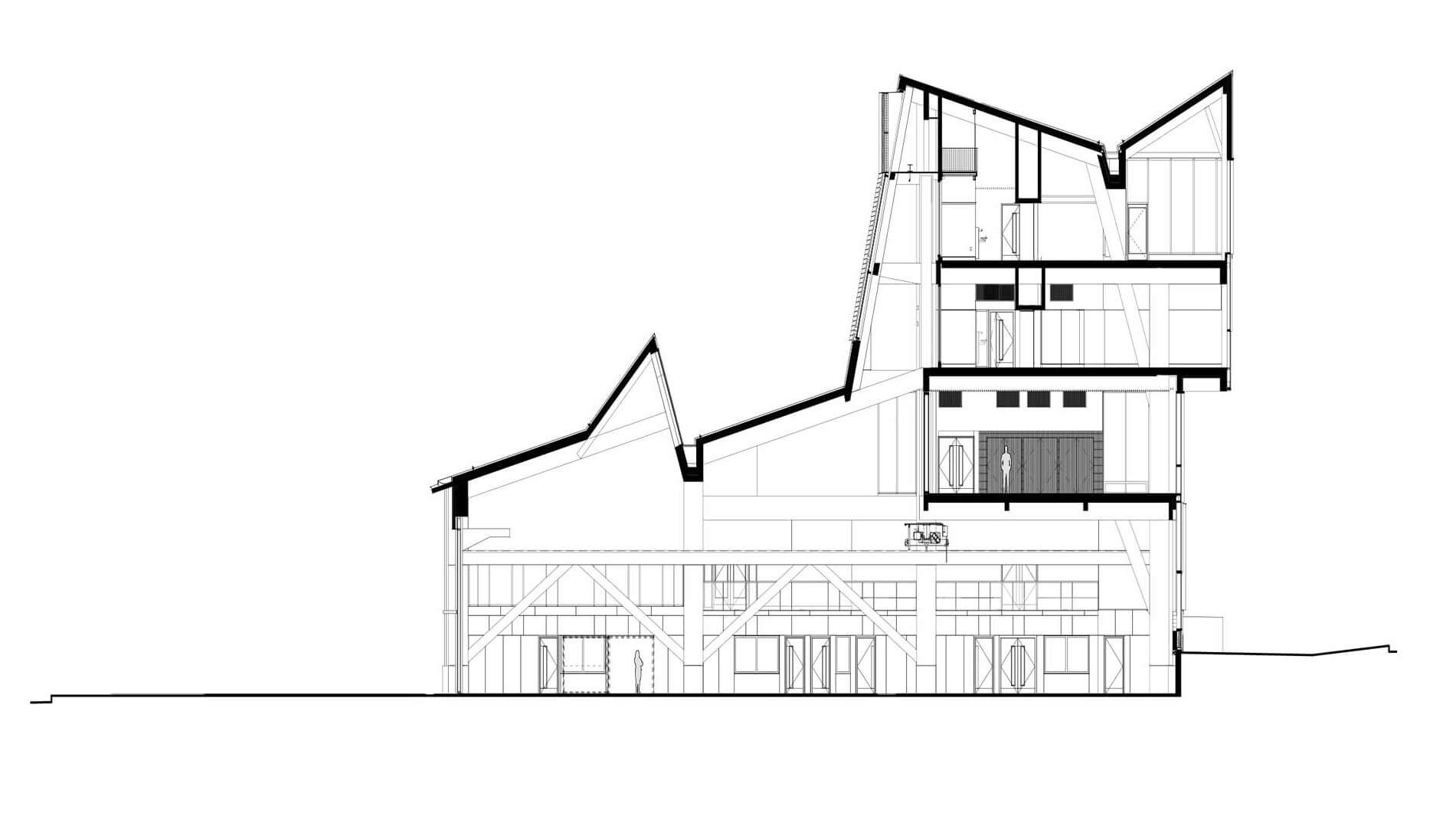

From the start, the directive for the building was that the ATC ought to be a “storybook of timber” to celebrate Arkansas’s forests and forest products. A prominent competition led to the selection of the Dublin, Ireland–based Grafton Architects, headed by Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara, in February 2020. A week later, they won the Pritzker Prize. The next month, the COVID-19 pandemic landed. The project proceeded, with some shrinkage: Originally proposed to be 6 stories, it is 4 stories tall but retains the spiky sectional play that is the core of its formal thesis. After interviewing the architects in 2022, I followed its progress with anticipation. When I visited for the opening at the end of August, the semester was already underway, with sketches on chalkboards and lumber piling up.

Timber on Top

The building’s sawtooth profile tops two programmatic zones: A stack of classrooms, studios, and seminar and conference spaces sit atop a double-height, 11,000-square-foot floor that houses a fabrication and design-build shop. The upper studio floors have windows that overlook the shop, and passersby on the street can peer down into it, a move that centralizes 1:1 construction as a key part of the school’s pedagogy.

The ATC, funded by a naming gift from the state’s largest privately owned timberlands and wood products company, is part of the growth of the University of Arkansas. When Dean Peter MacKeith arrived in 2014 and embarked on this building project in 2016, the Fay Jones School had 425 students. Today, enrollment numbers around 1,100. The main university campus is largely built out, which spurred the creation of the Windgate Art and Design District, a satellite area that houses art and design programs. The ATC is one of three buildings on here that will support art and design: HGA’s Windgate Studio + Design Center is on the other end of the block, and in between, a university art gallery designed by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects is under construction. Anthony’s Way, a parklet designed by Ground Control, offers a landscaped buffer between the ATC and its neighbor. While this trio of new buildings is a 20-minute walk from the main university campus, it’s also adjacent to Fayetteville’s Cultural Arts Corridor, bridging the university with the burgeoning local art scene.

The ATC is more intimate in person than you might expect from the photographs. At 42,000 square feet, it’s smaller than some of the country’s largest homes. (But its cost, $43 million, gives it a price tag of about $1,024 dollars per square foot.) Its flattened north elevation holds the street edge along a sloping site: One enters on the second floor, with the shop largely below grade, but on the opposite side of the shop level, a second entrance opens up with a large hangar door for easy load-in and access. The main entry is custom fabricated by local artisan Rachel McClintock, with a cast-metal door handle from Juhani Pallasmaa. Farrell is pleased with the frontage’s presence; she told me she thinks it “sits proudly, and not in an arrogant way. It says, ‘We’re a university timber building: Come all ye and have a look.’”

As foretold, the ATC is an advertisement for the possibilities of timber construction. Its massive structure—made from spruce, pine, and fir fabricated by Binderholz in Austria—is unavoidably present, and satisfyingly stocky. The eight columns that hold everything up are about 4 feet square and solid. The frames are pleasingly dotted with wooden plugs that conceal the bolted connections between pieces. The experience peaks when one is looking across through the upper areas, where the members of the queen post truss branch out to grab the roof. Above, the building is enclosed with domestic CLT panels from Mercer Mass Timber in Conway, Arkansas. The wood idea continues in the wall finishes and stairwells; even the glass guardrails are topped with cherry caps.

Outside, the taller zone is lined in a thermally treated southern yellow pine, in part as a response to a building-code requirement for noncombustible cladding above 40 feet, modus studio’s Jason Wright explained. A lattice of western red cedar lines the longer, lower elevations, spanning over windows, and a silver metal panel similar to the roof is used above. The top floor has covered porches on both ends, which open to views of the Ouachita Mountains, and the east elevation has the nicest exterior fire stair I’ve seen in years. The adventurous expression refutes the typical norms of wood construction; McNamara said she didn’t think they could construct a building like this in Ireland, the U.K., or France because of the exterior cladding.

A Place in the Making

The didactic structure is a fusion of the school’s messaging—both for its philosophy of hands-on making and the public university’s goal of supporting Arkansas’s economy—and the interests of Grafton Architects. In this, the architects’ first built work in the United States and the first to use mass timber, visitors can see a clear dedication to structural expression, as well as an appreciation of light and rhythm, which is nestled throughout the spaces within. Across their career together, McNamara said, the duo has been “combating the effect of mass production, because it very often takes the life out of the material.” Here, she’s delighted that the finished building feels like a “big chunk of timber.”

This formal interest is balanced by the firm’s empathetic, relational approach. For being world-class architects, McNamara and Farrell, along with their directors and project architects, are remarkably personable. They keep their atelier small—38 people, with 37 architects, McNamara told me—so that they can maintain personal connections to each project. And they have a keen interest in a wide range of cultural topics. They began their opening lecture with mention of the first architecture competition—in Greece in 448 BC, for a monument to commemorate a war victory—and continued on to discuss the Ogham stones, ancient rocks inscribed with the earliest forms of the Irish language.

As the school settles in over the semester, Farrell said, “we hope the students love it and make interesting things here.” The interior has exposed (but expertly coordinated) mechanical and electrical systems, which help it feel like an unfinished warehouse where emerging designers can make a mess in an unselfconscious manner, particularly in the shop, which is well equipped and spanned by a linear gantry crane.

Upstairs after the building’s dedication, I spoke with Trey Melton, a fifth-year undergraduate architecture major who had landed a corner desk. He praised the lighting before directing my attention to the tables, which were designed and made by the students. Despite the day’s festivities, he was already at work on an assignment in John Folan’s studio, which is researching the use of WLT, or wave-layered timber, a Finnish product that combines ruffled wood pieces without using glue. (Folan’s work through the Urban Design Build Studio with the technology is its first licensed use in the U.S.)

A Cornucopia of References

If Frank Gehry’s work owes a debt to fish, then Grafton’s nods to dinosaurs, though more to the creatures’ reassembled skeletons than their CGI-animated reproductions.The ATC is rich enough in form and idea to handle any referential projection. It has a Roman quality, as Oliver Wainwright noted. Early inspiration also came in part from the framing of historic Ozark barns. Robert McCarter, in an essay prepared for the opening, compared its two-part arrangement to a train hall paired with a train shed.

After a previous interview with the firm, I wrote that it looked like Giovanni Michelucci’s San Giovanni Battista or Theo Jansen’s strandbeests, but in person it is something like a billboard building. Wright said the profile was an “Ozark cross section” endemic of the Ozark Plateau, a region where, as historian Brooks Blevins describes it, “our hills aren’t high, but our hollers sure are deep.” Farrell also alluded to Fay Jones’s own work with wood like at Thorncrown Chapel, but perhaps the Arkansas architect’s own home, located near the campus, is a better analogy. It was built in 1956 with the idea of “the cave and the tree house,” as faculty member Gregory Herman explained during a tour of the residence, which the university now owns and maintains. At the ATC, the shop is the cave, and the studios are the tree house.

How sustainable is the ATC really? While the classroom floors are conditioned, the shop is heated but not cooled. Instead, the tall, enclosed area is topped with equipment to pull air up and out of the building. Plus the canoe-like beams shed water into bioswales for reuse. While there was carbon modeling, Wright said that in the end the math “doesn’t matter” because the building speaks for itself. (The project is targeting LEED Gold certification.) The more enduring point is the political message about the state economy, which overshadows metrics. ATC summons a lesson played out everywhere: The most sustainable building is the one that is beloved by its community.

Shaping the Future of Architecture Education

The ATC is cause for collective pride. Here is a building that you should go see on your own dime. Here is a building that demonstrates what is possible with timber construction. Here is a building that stands to make an impact on generations of students. Here is a building that will turn drivers’ eyes as they careen down MLK Jr. Boulevard and distract Great Value–laden shoppers exiting Walmart.

In a town whose name was lifted from Fayetteville, Tennessee, and for an institution whose first building, Old Main, was copied from the University of Illinois, Grafton Architects has delivered a remarkably original masterpiece, heroic and ordinary at once. Still, the founding spirit remains similar. Like the ATC, Old Main, the university’s oldest building, was built of local materials, including “wood milled from Ozark forests.” Both were dedicated on hot days in August, though with Old Main it was in 1875, 150 years ago. None of us will be here 150 years from now, but the ATC will be. Who knows what activities it will host then. Vita brevis, architectura longa.

Given its elephantine nature, architecture as a discipline is profoundly mismatched with the unhealthy speed of today’s brain-rotted cultural discourse. This slowness gives it the ability to resist and serve as a refuge. “Architecture is a silent language that speaks,” Farrell intoned during her opening lecture with McNamara. Also: “Architecture is an act of hope and belief.” This aligns with the optimism embedded in higher education, despite current attacks, as a venue where the wisdom of experience transfers to ambitious youth who will make tomorrow better than today. That’s the goal, at least. As Farrell said, “Education is the biggest gift you can give to the future.”

Project Specifications

This text contains homages to Herbert Muschamp’s review of Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao which was published in The New York Times on September 7, 1997.

A version of this story was published in the October/November 2025 print issue of The Architect’s Newspaper.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper