The Upper Canada College (UCC) Lindsay Boathouse occupies a stretch of Toronto’s Outer Harbour—a reclaimed, rugged peninsula that feels remote despite its proximity to the city. Designed by VJAA with Toronto’s RDHA as architect of record, the 9,400-square-foot building occupies a peninsula with both ecological sensitivity and public significance. This part of the Outer Harbour was formed through decades of lake-filling using construction rubble and dredged material.

The school—a 196-year-old institution that is a pillar of Toronto’s elite—has a long tradition of rowing. Its team trained for decades out of a nearby facility in two Quonset huts.

For the new facility UCC reached out to Minneapolis-based VJAA, which had previously completed three rowing clubhouses, including one for the Minneapolis Rowing Club in 1999. “So many architects are involved in the sport, and we realized that it has aesthetic aspects that are aligned with architecture,” said VJAA principal/CEO Jennifer Yoos. “The equipment is beautiful. The rowers work together in rhythm.” Racing boats, known as “shells,” are traditionally made of wood; their long profiles and exposed structure of bent wood provide an easy analogy to a building, particularly early–20th century factories. Yoos notes that the boatbuilding analogy extends to joinery and material efficiency—every element serves a structural purpose, with minimal superfluous mass.

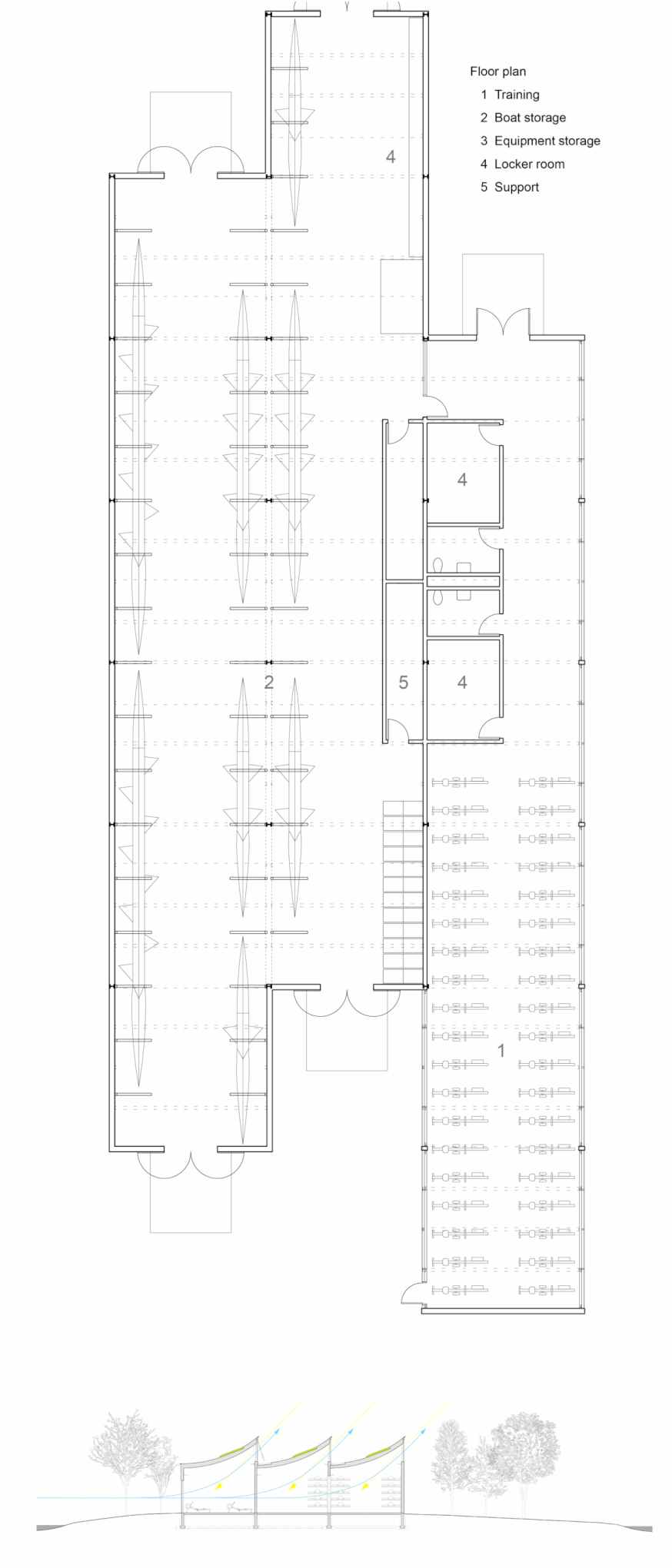

The Lindsay Boathouse, named after a donor, wields that symbolic language with quiet precision. It encompasses three black bar-shaped forms that slide past each other like boats racing toward a finish line. Two of these are connected and provide storage, while the third, on the south side, houses a training gym and office space for the team’s coach.

Just as today’s shells are made of fiberglass and carbon fiber, the building takes a strategic approach to structure. Piles are driven deep into the soil, which is peppered with large chunks of concrete and masonry rubble, remnants of the site’s landfill past. A structural concrete slab supports a light steel frame, while panels of cross-laminated timber form the walls, their knotty, textured surfaces left proudly exposed. On top, a wood roof deck curves into three concave arcs that cradle north-facing clerestory windows. The storage zone houses approximately 40 boats on bespoke racks, their hulls stretching out lengthwise beneath the curves of the roof. Widely spaced columns allow even 12-seater boats to be moved comfortably in and out.

The building also welcomes natural light through a south-facing wall of glazing along the workout zone. These windows frame views across a small bay toward Toronto’s downtown skyline. At the west end, where the boathouse reaches toward the launch, the structure opens up with glass on two sides, providing natural ventilation as well as immersing occupants in the shifting light and breeze of the waterfront.

The entire building relies on passive heating and cooling, part of the school’s deliberate effort to minimize the project’s footprint. The site rests within a delicate ecosystem that is gradually occupying the shoreline here, much of which is artificial. (Tommy Thompson Park, an entirely man-made peninsula that has become an important sanctuary for migrating birds, is nearby.) And yet the building sits less than a mile from where the $1 billion USD reconstruction of the Don River was recently completed, opening the way for future development of the port area.

The site is publicly owned, and municipal agencies plan to expand an existing network of pedestrian and cycle trails into this area. The boathouse leaves space along the shoreline for these future additions. Its foot- print and siting were coordinated with the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority to maintain a buffer for vegetation and potential fish habitat improvements. The docks were aligned to avoid disturbing aquatic vegetation that serves as spawning grounds for native fish species.

For now, the boathouse remains a quiet outpost—an escape for UCC’s students and, in summer, for day campers bused in from downtown public schools. Its low profile, warm timber walls, and operable windows reinforce a tactile connection to nature.

“Having natural ventilation pass through the building is sustainable,” said VJAA project architect Nate Steuerwald, “but it’s also about connecting yourself physically to the landscape—not just looking through a window but feeling the air move.”

Alex Bozikovic is the architecture critic of the Globe and Mail and the author of books including 305 Lost Buildings of Canada.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper