The subject of Architecton, a new documentary, is ostensibly architecture. But unlike Brady Corbet’s recent psychological fantasy The Brutalist or Francis Ford Coppola’s lamentable fever dream Megalopolis, this film arrives with a pointed message about the problematic—and widespread—use of concrete, a virtually unrecyclable material. Instead, the film pleasingly unfolds as a lyrical, impressionistic journey more in the spirit of Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi trilogy. The title Architecton literally means “master builder” in Greek, and, for Russian filmmaker Victor Kossakovsky, “it’s another way of saying ‘master of the universe,’ right?” he recently told AN.

Kossakovsky was inspired by Kyiv-born avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935), who made “arkhitektons,” austere blocks arranged in complex combinations in what he called “architectural Suprematism,” after his Suprematist paintings (think Black Square [1915] or White on White [1918]). Kossakovsky is the director behind the acclaimed films Vivan las Antipodas! / Long Live the Antipodes! (2011)—which contrasts two cities located diametrically opposite each other on the earth’s surface—and Aquerela (2018), about the power and beauty of water. He has said that Architecton is the third and final film in this trilogy.

A producer advised him against using the title, but the director happened to read War and Peace and was amazed that Tolstoy employed the term “architecton” toward the end of the book to connote a god’s-eye point of view, shifting between characters’ perspectives, historical events during the Napoleonic Wars, and social customs, similar to cinematic storytelling modes that give readers total immersion in the story. This echoes the filmmaker’s ambitions to create a holistic approach to the depiction of the environment, natural and built.

Architecton’s scenes stage visuals of cities and landscapes, moments of beauty and banality, and the dichotomies of sustainability and waste. More than architecture, the film is really about creation and destruction.

To get the point across during its tidy, 97-minute run time, cinematographer Ben Bernhard employs high frame rates, slow-motion pans, and drone shots. The film opens with a prologue of bombed-out buildings in Ukraine, with tower blocks ripped apart, with the remnants of lives on display—although there are no signs of life. Kossakovsky, a Russian now living between Berlin and Barcelona, told AN that “Russia is making such a catastrophe. I feel such guilt. If you look [at] the ruins in Ukraine, you know who is guilty. It’s from Russia, and you see how they destroy residential buildings when people are sleeping.”

But the destruction doesn’t end there: “On top of everything, we have a war with nature. We cannot win. It’s something wrong with the architecture of the world we create.” He also incorporates footage of the devastation wrought by the Turkish earthquake in 2023.

Kossakovsky maintains there is much to be learned from ruins. In his view, we should incorporate those romantic sensibilities in new construction, both in aesthetics and material use. “Generally speaking, ruins are more important than any written document, because normally, written documents are written by winners,” he said. Kossakovsky admires Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–78), whose black-and-white etchings of ancient Rome, which Kossakovsky maintains are so accurate they are almost photographic, inspired the black-and-white sequences he shoots of exploding rock quarries that cascade boulders down like an avalanche. The director also lovingly films Cretto di Burri in B&W, a white-concrete landscape artwork by Alberto Burri (1915–95) begun in 1984 and built on the ruins of Gibellina, a Sicilian town leveled by an earthquake. It is “a concrete scar in the landscape,” as Kossakovsky called it, which mimics the original streetscape.

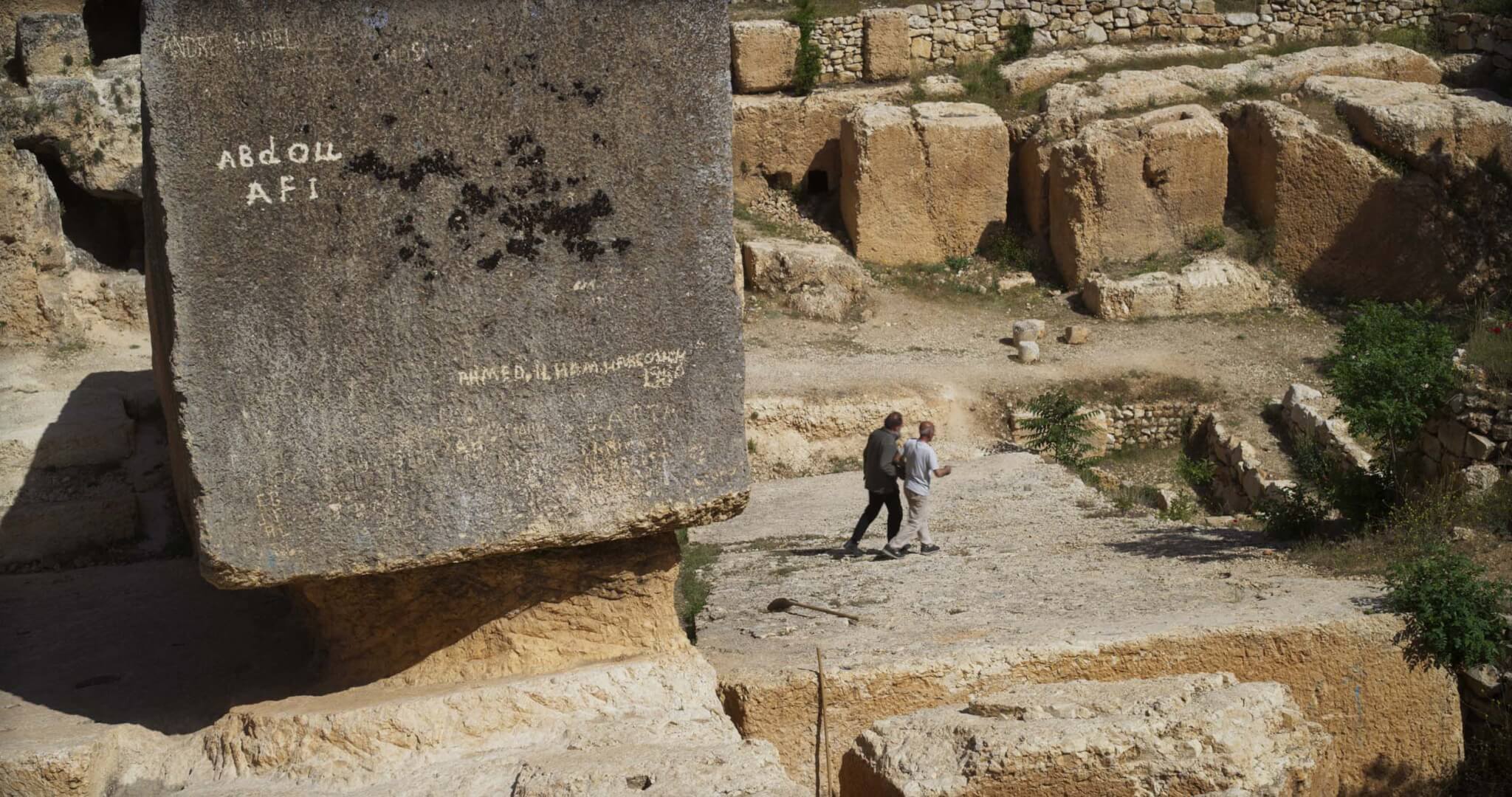

The only architect who appears on camera in Architecton is Michele De Lucchi, founder of AMDL CIRCLE. (Kossakovsky approached several others and ended up pairing with De Lucchi.) In the film, De Lucchi travels to the ancient ruins of Baalbek, the City of Cyclops, in Lebanon, where enormous pieces of stone were used to create temples—but no one can figure out how the stones were moved or how the temples were constructed. Kossakovsky wanted to show off “this part of the world that is just made [of] stone. In one way, I want to show how badly we treat stones and how we grind them for cement. But on the other side, it’s also enhancing how beautiful the stuff we did was in the past and how much stones are a witness to the ability of humans to create. So, it’s a way to accuse and a way to celebrate the human production of artifacts.”

De Lucchi returns home to his garden in Lombardy, where he oversees the creation of a perfect circle of stones; humans cannot enter, but animals can. It is then the site of a closing conversation between the filmmaker and the architect. In that exchange, Kossakovsky questions why a “people who knew how to make buildings which lasted thousands of years […] build buildings that only last 40 years? Why do we build ugly, boring buildings if we know how to build beautiful ones?”

De Lucchi offers a slant reply: “Everything that has no fertility inside is dead. And it’ll stay ugly forever. Everything that is fertile and grows and develops and comes back to a new life—that is what we need: to find a new idea of beauty.” Architecton offers lyrical images that pack an existential punch. De Lucchi continues: “Architecture is just a way to think about how we live, and how we behave. There is a famous sentence that we say: ‘When we design something we do not design only products, buildings, or spaces, but we design the behavior of people.’”

Susan Morris works across media—film, television, radio, exhibitions, public programs, print, digital media— specializing in the arts and culture with an emphasis on architecture and design.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper