City and federal officials say there’s no choice but to seek “creative” solutions to the New York City Housing Authority’s (NYCHA) alleged $78 billion funding deficit. Chief among them is RAD/PACT (Rental Assistance Demonstration/Permanent Affordability Commitment Together), a program that shifts the management of public housing into the hands of private or nonprofit developers. Supporters frame it as a lifeline. Critics say it’s privatization by design.

Nowhere is this tension more visible than in the proposed demolition and redevelopment of the Fulton, Elliott, and Chelsea Houses (FEC), a flagship RAD/PACT project in Manhattan’s West Chelsea neighborhood that dates back to 2019, and has since undergone myriad controversial revisions. The latest design—by Related Companies, Essence, Practice for Architecture and Urbanism (PAU), COOKFOX, and ILA—has ignited fierce backlash from residents, housing scholars, and community advocates.

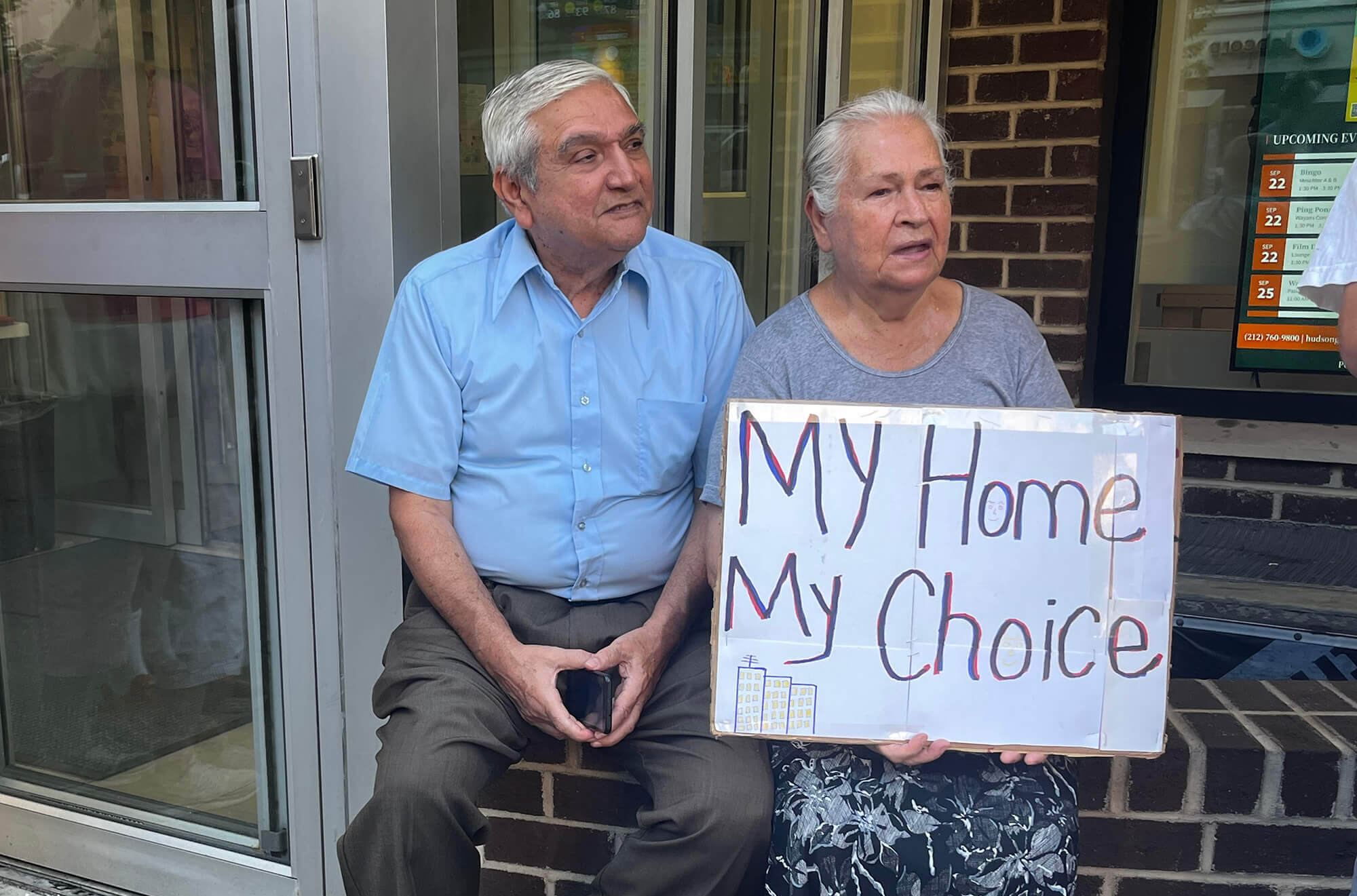

Renee Keitt, Elliott-Chelsea Houses Tenant Association president, and Layla Law-Gisiko, a district leader in Assembly District 75, recently spoke on NY1 about how elderly FEC residents have been issued 90-day notices to vacate their homes. With its soaring towers, full demolition of NYCHA buildings, and a unit mix dominated by market-rate apartments, the plan is seen by many as a top-down development strategy dressed up as revitalization.

According to the final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) shared this June, the penultimate FEC proposal touts 20 percent affordable housing, a staggering drop in relation to previous iterations, and towers that nearly double the heights of the original proposal. While officials point to upgrades, rent protections, and the promise of “right to return,” the underlying RAD/PACT structure tells another story—one of displacement, land extraction, and public-to-private transfer.

What is happening at Fulton, Elliott, and Chelsea is not just about three campuses, however. It’s about the future of public housing in New York—and by extension, the future of the city itself.

From Public Good to Private Asset

NYCHA is North America’s largest public housing system. It is home to nearly half a million, mostly low-income Black and Brown residents, and in the midst of a slow-motion crisis, shaped by decades of disinvestment, crumbling infrastructure, and mounting repair costs. It was once the pride of civic infrastructure, created to ensure safe, stable homes for working class New Yorkers. But decades of disinvestment, bureaucratic neglect, and political abandonment has left NYCHA in crisis. Today, more than 500,000 residents live in buildings plagued by mold, leaks, broken elevators, and decaying infrastructure.

What’s often presented as a technical or budgetary problem is, in truth, a political one. For years, federal support for public housing has steadily declined, beginning with the Reagan administration and continuing under both Republican and Democratic leadership. Adjusted for inflation, funding has dropped even as the need for affordable housing has skyrocketed.

That decades-long withdrawal has produced a $78 billion capital repair backlog—a figure that now functions as justification for privatization, mentioned above. Programs like RAD/PACT are pitched as solutions, shifting the management of public housing to private and nonprofit entities. In return, buildings are converted into Section 8 properties, often through complex webs of tax credits and financing.

But this isn’t just an administrative tweak—it’s a fundamental change in housing philosophy. Where once public housing was treated as essential infrastructure, it is now increasingly viewed as a liability to be “unlocked” for private capital.

The Land Beneath Our Feet

NYCHA owns over 2,400 acres of land across the city—much of it underbuilt compared to the surrounding neighborhoods. In a real estate market as aggressive as New York’s, this public land is seen less as a public resource and more as a development opportunity. But former Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s framing of ‘filling in’ the ‘empty spaces’ on NYCHA campuses as an innocuous urban strategy fails to recognize the critical social and environmental functions these spaces serve.

NYCHA campuses have much higher density than typical urban blocks, and the open spaces and trees on these sites provide essential green infrastructure. These areas not only mitigate the urban heat island effect but also offer residents limited but vital access to nature and recreational space, contributing to their physical and mental well-being.

By advocating for infill strategies—often promoted by firms such as Peterson Rich Office and PAU—this approach risks erasing spaces that are indispensable for the health and cohesion of already vulnerable communities. In prioritizing development over these open areas, such strategies overlook the long-term consequences of diminishing environmental equity and further marginalizing communities already struggling with scarce resources.

Through infill strategies and ground leases, NYCHA campuses are being opened up to private developers in exchange for promises: better buildings, greener designs, mixed-income units, and some level of affordability. But critics argue that what’s being offered is less a renewal and more a repackaging—a transfer of public land into private hands under the guise of modernization.

The PAU proposal for FEC makes that tension visible. Located just blocks from Hudson Yards and the High Line, the sites are among the most valuable properties NYCHA owns. In the proposed plan, luxury towers would fund repairs and upgrades, but also dramatically reshape the character of the neighborhood—and the lives of the people who currently live there.

Once demolished, these communities rarely come back the same, if at all, as was the case with Cabrini Green in Chicago. The social networks, tenant leadership, and cultural continuity that define them are fragile—and often lost in transition.

Participation Without Power

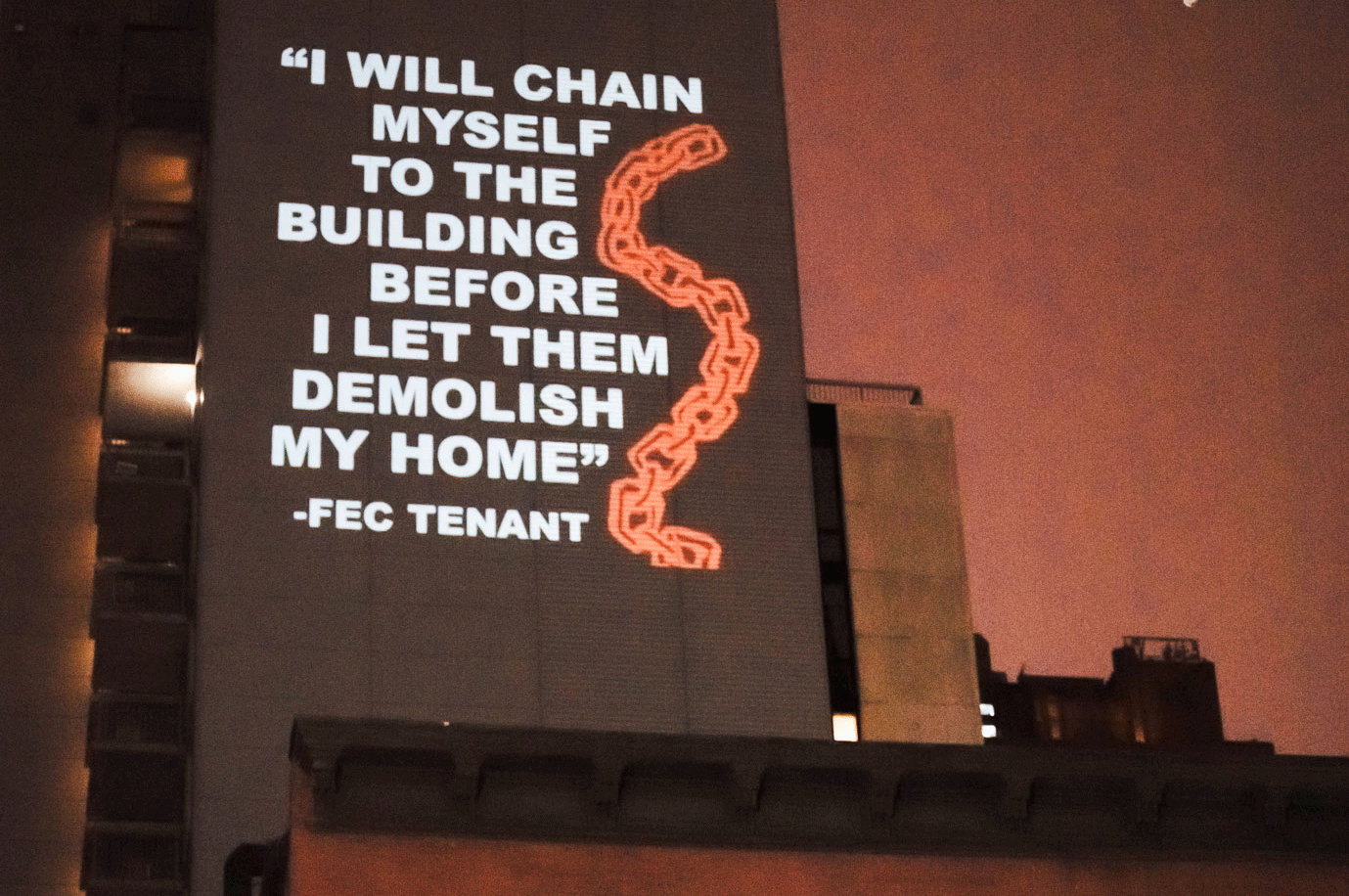

One of the most persistent criticisms of NYCHA’s redevelopment efforts is the lack of true resident engagement. Meetings are often framed as updates rather than forums for decision-making. In recent years, FEC residents who oppose demolition and privatization have in fact been barred entirely from these meetings. Tenant associations are sidelined, while key financial and architectural choices are made behind closed doors.

This is not just a communication problem—it’s a democratic one. Public housing residents are expected to accept plans that deeply affect their homes and futures without meaningful input. At best, they’re offered the right to return; at worst, they’re treated as obstacles to progress.

In Chelsea, grassroots groups like the Chelsea Coalition, Save Section 9, and Fight for NYCHA have pushed back, demanding tenant-majority oversight, full transparency, and long-term public ownership. Their message is clear: public housing should not be handed over to private interests in exchange for short-term fixes.

Despite decades of neglect, NYCHA still matters. It shelters hundreds of thousands of people. It keeps families in their neighborhoods. It offers something increasingly rare in New York City: housing that is not ruled by profit.

There Are Other Ways Forward

Alternatives to privatization exist, such as the Green New Deal for Public Housing and the Public Housing Preservation Trust. The Green New Deal proposes retrofitting and repairing NYCHA’s buildings through public investment and union labor, all while keeping public ownership intact. Similarly, the Public Housing Preservation Trust offers a mechanism for funding repairs without selling off public assets, thus ensuring continued public ownership and accountability.

However, these proposals have faced pushback from advocates like Louis Flores at Fight for NYCHA, who argue that such models, while seemingly protective of public housing, still risk weakening tenant control and accountability in the long run. Flores and other critics warn that these plans, while addressing physical repairs, might fail to address the systemic issues of governance and tenant engagement that are central to the sustainability of public housing.

These ideas start from a different premise: that housing is infrastructure. Like schools, libraries, and transit systems, it should be funded, maintained, and governed for public benefit—not financial return.

Will we continue down the path of market-based “solutions” that transfer public value to private hands? Or will we commit to rebuilding our housing system as a public good?

Design plays a central role in that decision. Architects and planners can choose to amplify the logic of displacement—or challenge it. City agencies can prioritize short-term deals—or invest in long-term public stewardship. Residents can be treated as clients—or empowered as co-authors of their communities.

The fight for NYCHA is more than a policy debate—it’s a question of who the city is for. And whether the spaces where we live will be shaped by profit, or by the people who call them home.

Viren Brahmbhatt is an architect and urban designer based in New York City. He is the founder of de.Sign Studio and an adjunct professor at CCNY’s Bernard and Anne Spitzer School of Architecture. He has also taught at Columbia GSAPP, Washington University’s Sam Fox School, and Pratt Institute. Previously, he contributed to the NYC Housing Authority’s Design Department.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper