The Many Lives of Nakagin Capsule Tower

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

New York

Through July 12, 2026

Whether one would want to live inside a Nakagin Capsule depends on a few critical factors: under what physical conditions and on who else lives in the building. The answer to the provocative question is as varied and complex as the many lives lived in—and lived by—the modern, now demolished icon designed by Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa in 1972 in an upscale district of Ginza in Tokyo. It is one of a few built works of architecture by the Metabolists, a group of avant-garde Japanese architects who sought to develop a mode of non-Western modern architecture. Visitors to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) can ponder this question at the recently opened exhibition The Many Lives of the Nakagin Capsule Tower.

The exhibition opened on July 10, just over three years after the building’s controversial demolition, which followed years of debate over its preservation. Twenty-three capsules were saved, one of which MoMA acquired for its collection and now exhibits in a street-facing gallery.

In “An obsolescent masculine dream,” my contribution to AN’s five-part series on the Nakagin Capsule Tower, written in remembrance of it in 2022, I posit that, at the time of its demolition, the building had reached obsolescence both culturally and physically. Seeing the exhibit and encountering the recent former residents at the show’s opening, I revisited my prior assertions. The exhibition led me to question if adaptation of the capsules saved the building from cultural obsolescence. I also wondered if the physical obsolescence helped to spawn a community of preservation activists, artists, and interlocutors for whom the architects had not designed.

There are roughly three generations of people that occupied the Tower: first, the elite salarymen for whom the architects designed; second, those who, after Japan’s economy bubble burst in the late 1980s, occupied the Tower for its convenient location and cheap rent; and finally, those who, at the end of the building’s life, were there for its striking appearance, cultural significance, and sense of community. Twelve former residents, mostly of the third generation, attended the exhibition opening, some of whom had participated in interviews featured in the display. Now, 53 years since the building opened, the first occupants of the capsules would be in their late-70s or older, if they are still alive. The members of the first two waves were not at the exhibition opening and their voices are not heard in the gallery, leaving us to wonder what they would have to say about the exhibition and their lives in the capsules.

A Futuristic Vision and the Lived Realities

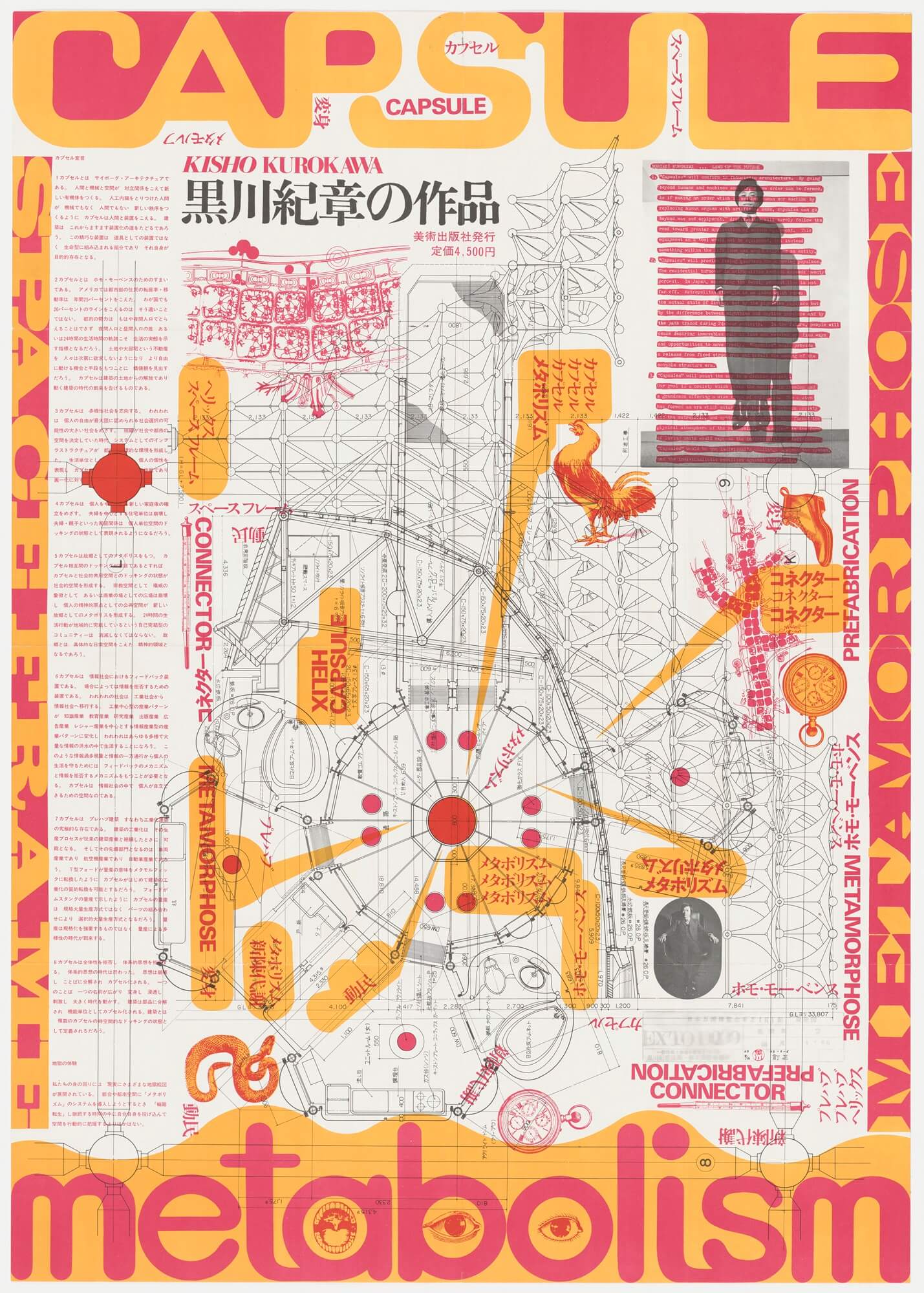

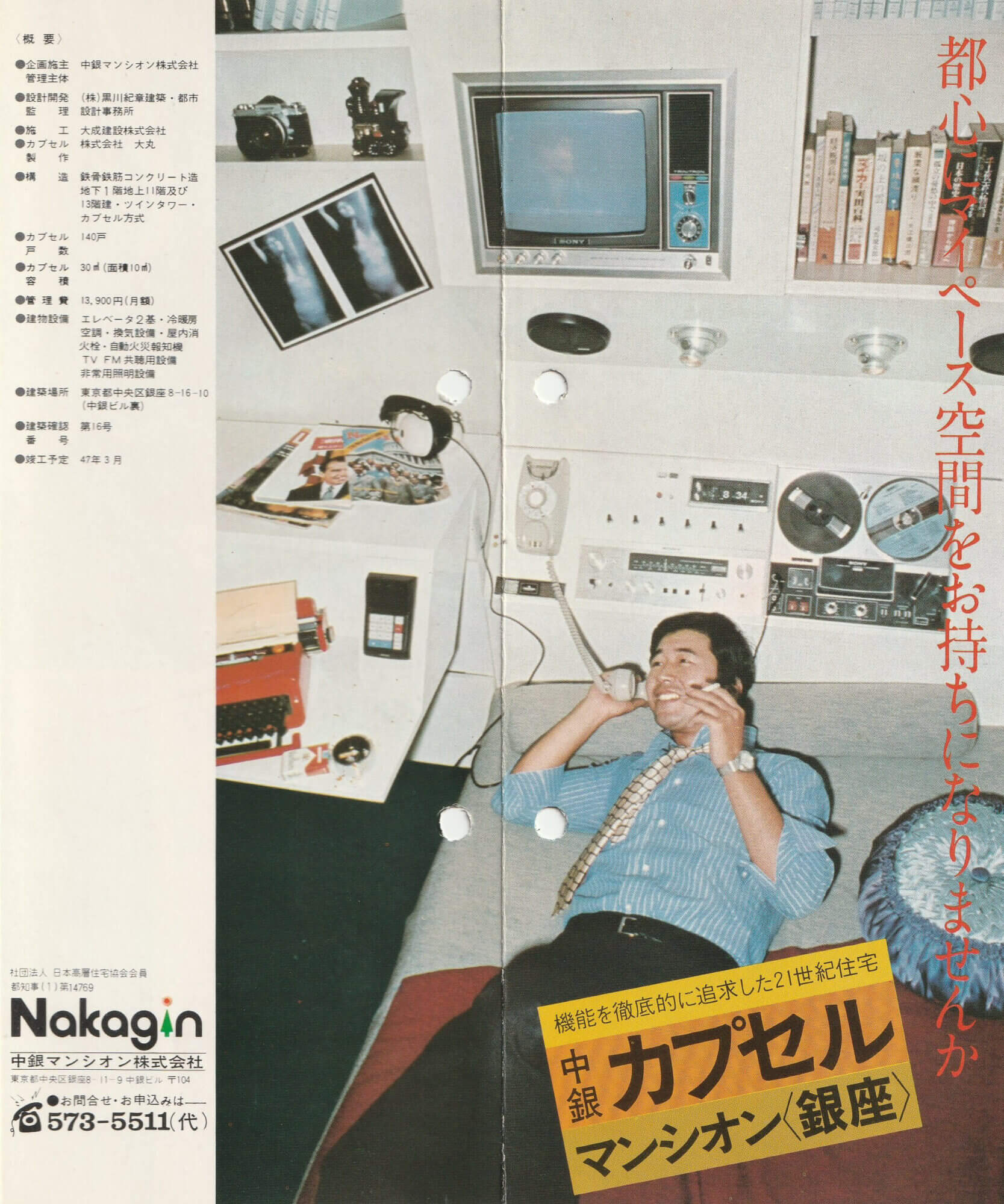

The first half of the gallery shows the building as the architect and the client (the real estate company Nakagin) presented to the public. In addition to the original drawings and models by the architect’s office, there is a poster, designed with fellow Metabolist Kiyoshi Awazu, visualizing Kurokawa’s manifesto on prefabrication, capsules, and spaceframe construction. The Japanese masculinity of the 1970s emanates from the original promotional materials exhibited adjacent to the drawings. A 1971 sales brochure by Nakagin Company features a salaryman with a tie lounging on bed while smoking and holding a telephone handset, surrounded by a built-in Sony stereo system, an Olivetti Valentine typewriter, and English magazines. In a marketing video by Taisei Construction Company, the architects—all men, wearing pressed business suits and with cigarettes in their hands—present their visionary ideas of capsule living and novel concrete and steel prefabrication methods.

In the second part of the gallery, the fully restored capsule unit A1305 takes center stage. Surrounding the capsule is a virtual tour of the building created with digital photogrammetry of the two concrete cores and the capsules; photographs of capsule interiors by Noritaka Minami; and videos of interviews with a few of the building’s last residents. In an interview with DJ “Koe-chan,” a mother who streamed music from the capsule between childcare tasks, she wonders how intriguing it would be to have people convert each of the 140 capsules for new uses, including those that are in ruins. Any curious visitor viewing the restored capsule, if asked if they would live here, may exclaim, “Yes!” The thrill of the futuristic vision and form is undeniable. However, it behooves the visitors to take note of the lived conditions of the building, which may lead them to other conclusions—the conditions may dissuade some, while enticing others.

Minami’s photographs and the 3D scans lay bare the lived-in states of the aging tower that unit A1305 cannot. Most capsules had rusted and deteriorated due to water leakage and the lack of maintenance. Over the past couple of decades, the Tower failed to meet basic needs, include hot water, air conditioning, heating, operable windows, and well-lit corridors. During my Airbnb stay in 2014, the very few people I saw in the building were all men, and majority of the capsules had been abandoned. At the time, the preservation activists had recently begun to purchase the capsules one by one, but a larger community of residents emerged in the years leading up to the demolition. In those final years, a DJ, designers, students, and preservation activists—over half of whom were women—found themselves at home in the Tower intended for men in pressed suits. They bonded over unexpected inconveniences, like an elevator outage and a signup-sheet for a shared prefabricated shower unit placed outside on the Tower’s podium and squeezed over a dozen people in a capsule for social gatherings.

The Possibility of Alternative Lives

These bonds among residents are not unlike those in communities that have formed around adaptive reuse of akiya, or empty houses that have become abundant across Japan due to its shrinking population. Rural homes in particular have attracted people escaping cities in Japan as well as those from abroad who buy for low prices and renovate them. In urban areas, post-war public mass-housing, or danchi, have recently been adapted to meet the current societal needs. In the last years of its life during Japan’s post-growth years, the Nakagin Capsule Tower participated of in metabolizing of abandoned homes.

The lives of the recent residents presented by the curators demonstrate that, although the building reached physical obsolescence—or because of its state of decay—it attracted a community with cultural ideals that counter those from the time of building’s inception. The residents adapted their capsules for a variety of uses not intended by the architect. While I maintain that 1970s Japanese masculinity that shaped the Nakagin Capsule Tower—which excluded women and family and denied of domesticity—is obsolete, the exhibition left me optimistic that alternate lives in the capsules are possible.

Aki Ishida is an architect, educator, and writer currently serving as Sam and Marilyn Fox Professor and Director of College of Architecture at Washington University in St. Louis. She was born and raised in Tokyo in the 1970s.

→ Continue reading at The Architect's Newspaper