Steve Earle’s “Fifty Years of Songs and Stories” concert at Saratoga Springs’ Universal Preservation Hall Thursday, June 5 brought everything in its straightforward name: a joyous, yet often poignant, romp down Earle’s long, varied career, which has landed him three GRAMMY awards and culminated in his nomination to the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame and membership in the Grand Ole Opry last month.

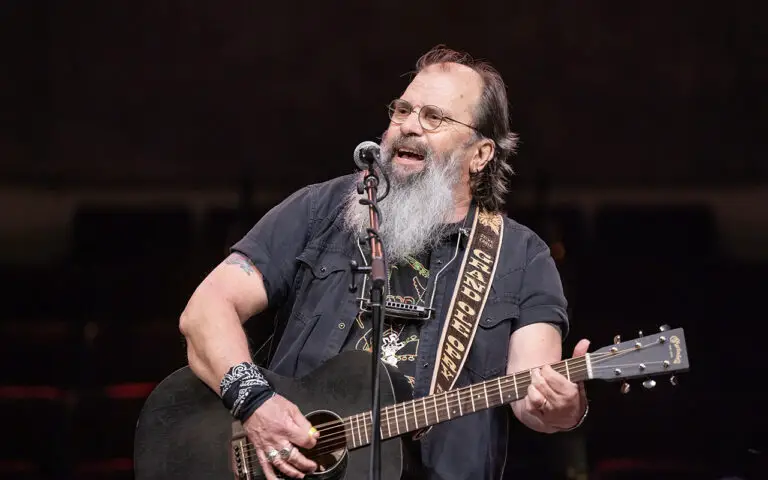

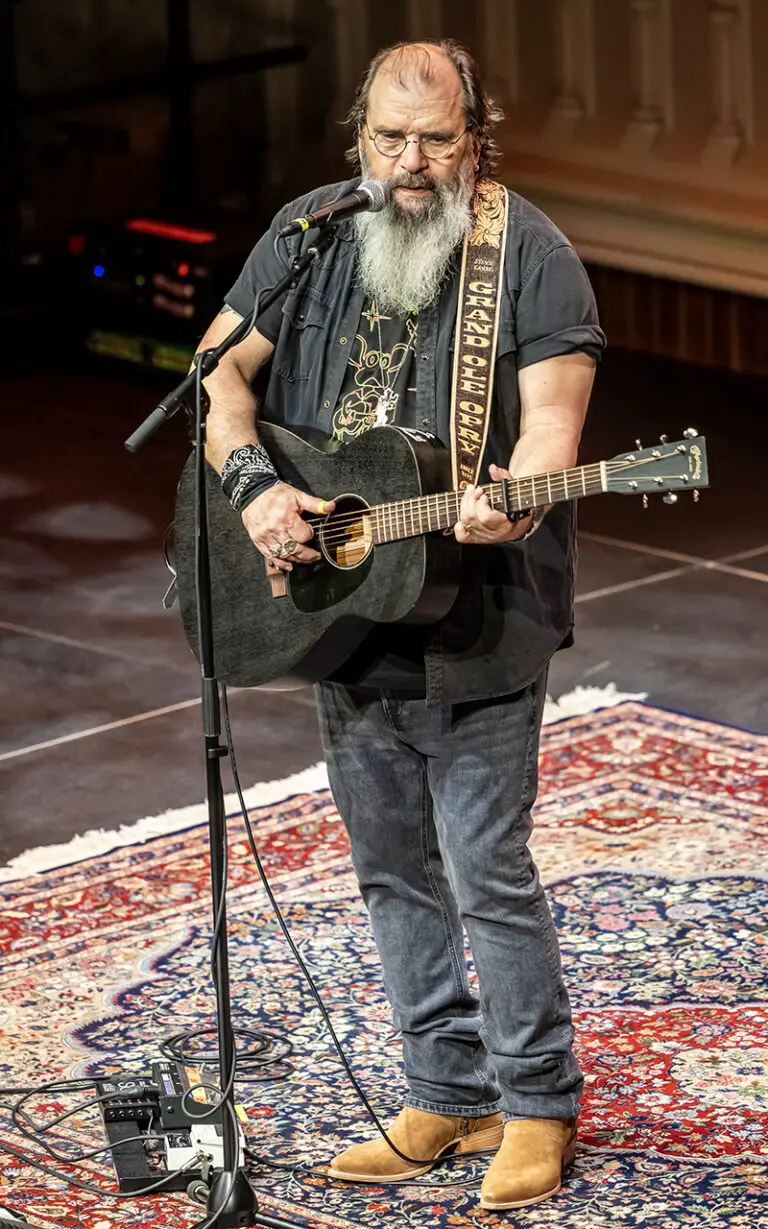

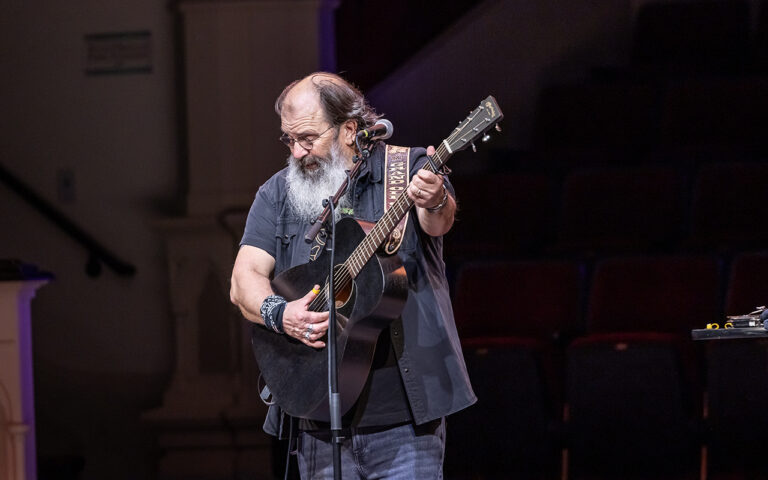

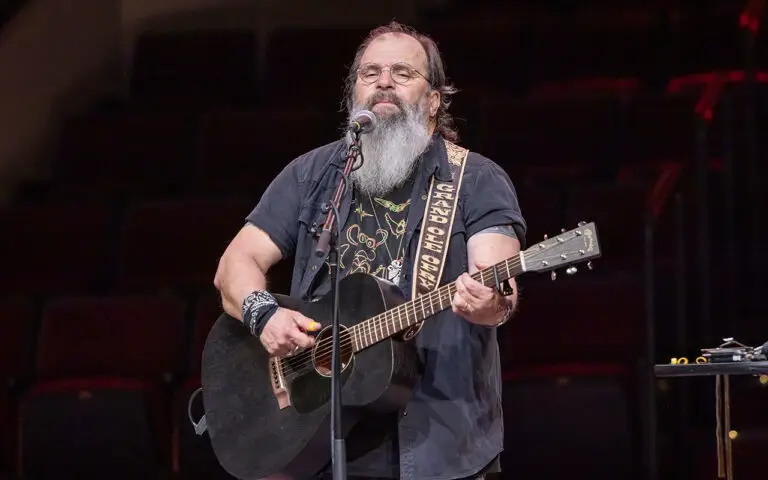

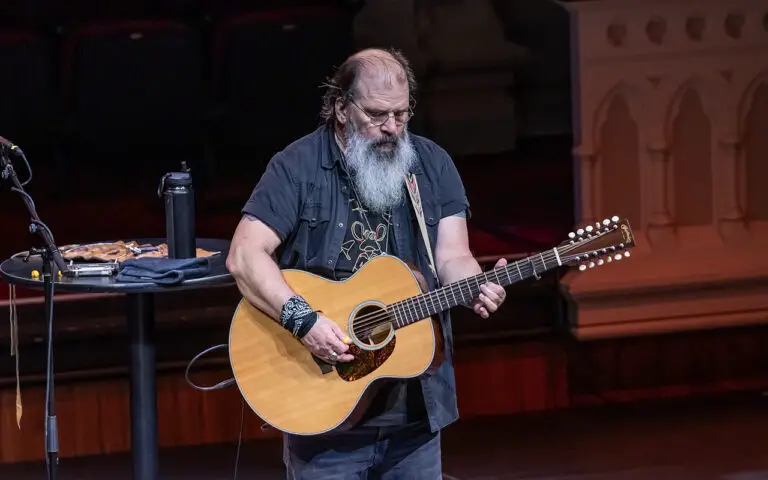

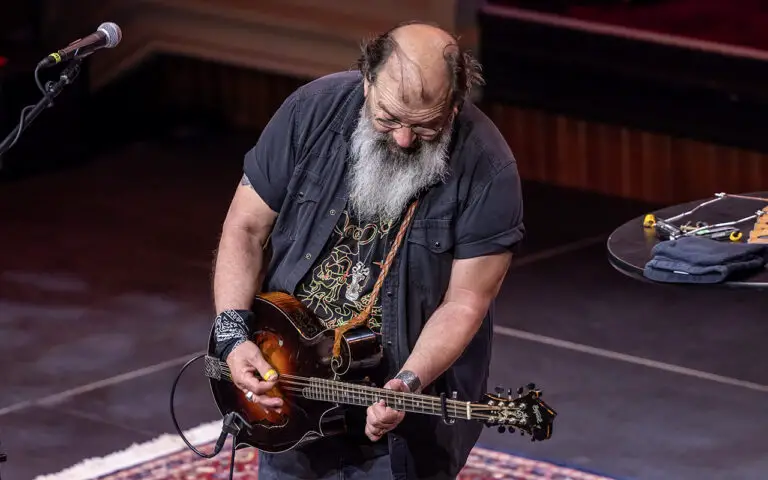

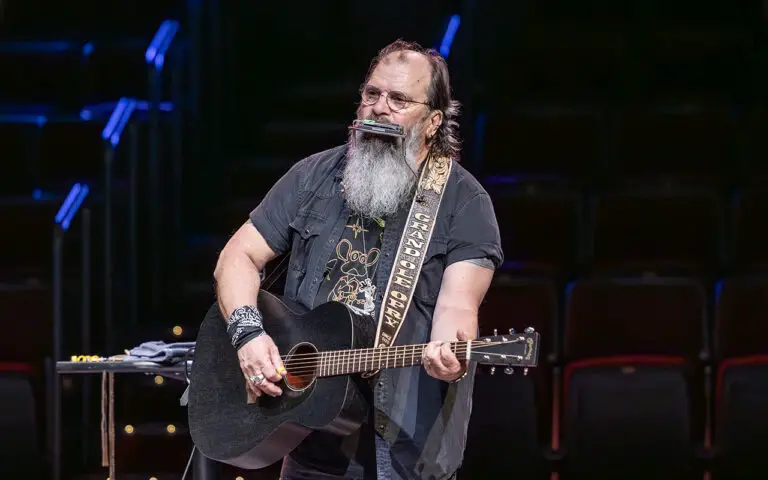

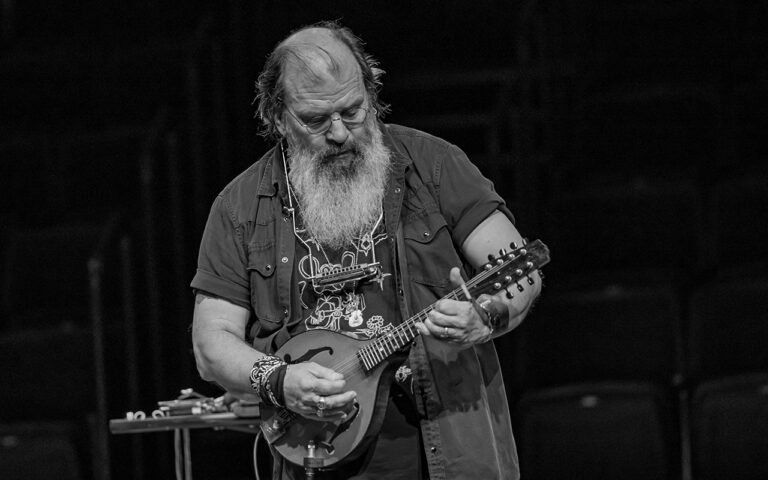

Dressed in faded black jeans and work shirt over a black tee and sporting a full white beard, Earle shared his raw, unfiltered storytelling from start to finish, silencing the audience during ballads, and rousing them to head-nodding, foot-tapping and clapping in time with blues, bluegrass and folk numbers.

As much a retrospective as a performance, the show sandwiched diverse musical styles and instrumentation with humor, lengthy anecdotes and back stories that prompted life changes or song inspirations as Earle traced the history of his youth in San Antonio, TX to his move to Nashville, the production of his albums, his drug addiction and recovery, the death of his son five years ago to fentanyl and his evolution as an artist.

At various points, Earle dropped industry names that had been influential, from the Oak Ridge Boys, Neil Young and blue grass mentor John Hartford to Bruce Springsteen and Shawn Colvin. Per one anecdote, Earle credited Springsteen with unknowingly helping his career when the Boss was caught buying Earle’s first album, Guitar Town, under the press’s watchful eye and the story went viral.

“That week I sold 35,000 records and was booked on the Tonight Show,” Earle said.

Relative newcomer Zandi Holup, who started her career with a TikTok following, opened for Earle and shared his gift for bittersweet yarn spinning, baring some of her personal struggles with substance abuse, loneliness, suppression and relationships, themes echoed by Earle in his stories and lyrics.

“I hope y’all like really, really sad songs,” Holup said, prefacing her 40-minute solo guitar performance in a white dress and bare feet and leading off with Gas Station Flowers, a lament about a precarious relationship rife with missteps and apologies.

“I’ll take you drunk, I’ll take you stoned, I’ll take you back as long as you come home,” Holup crooned. “These gas station flowers… are better than being alone.”

A similar thread of quiet desperation, backsliding and the search for redemption infused many of Holup’s songs, with lyrics such as “I could be your angel if you love these dirty wings” in her second number, “I found strength knowing I was weak,” a tale of getting sober; “I wish I was a preacher’s daughter…an angel dipped me in the water back in Tennessee. I wish I was a preacher’s daughter. I wouldn’t be like me”; and “I’m still in pieces, tryin’ everything from Jack to Jesus” or “Maybe I’m too broken, too cut wide open…too jaded…overmedicated…[There’s] a lot of things I don’t want to feel…I’ve hurt people, it’s true. I’m sorry if I’m hurting you.”

“Like everyone in this room, I have a past,” Holup confided at one point. “One I’m not completely proud of, but I’m trying to become a better version of myself.”

Holup wound down with “one happy song,’’ If I’m Too Much, Look for Less, a celebration of independence from the confining judgments of others. She closed to a standing ovation with “Wildflower,” a testimonial to freedom and her journey toward self-acceptance and personal

Holup, like Earle, commanded her inflections, tempo and volume to reel in her listeners, adding to the effectiveness of her storytelling. Strong lyrics with relatable messages were key in both performers’ repertoires as they alternated delivering powerful word images with robust, throaty vocals then soulful, hushed or even breathy tones when the time was right.

Earle opened strong with a gravelly rendition of Tom Ames’ Prayer, one of three songs he wrote in 1975 and still plays, he said, and followed up with Ben McCullough and its Civil War references.

In his third song, The Devil’s Right Hand, a trademark outlaw country number with a refrain of “Mama set a pistol in the Devil’s right hand,” Earle introduced harmonica. The lilting, simple repetitions were reminiscent of John Prine’s work.

Earle told the audience that he struggled with “being too commercial” early on in his career and was told “just write yourself an album,” He credits going to a Springsteen concert with a “light bulb going off” and the resulting in the title cut of Guitar Town in 1986.

“It took me 13 years to get a record deal and you earn something about storytelling,” Earle said during his two-hour set. “People don’t give a shit about what I feel or think. What they care about is what I think or feel that they can relate to. Empathy is what it’s all about.”

Consequently, Earle moved away from first-person narrative voice, experimenting with taking on the persona of another, as in the tale of Billy Austin, a death row inmate who had held up a filling station, shot a clerk and been condemned despite calling the police to report his crime. In the closing phrases, Earle, as Billy Austin, asks softly to the pastor giving last rites and the executioner, “Could you shave off all my hair…could you pull that switch, sir…then go home and tell yourself, sir, you’re better than I am?”

After a lengthy mid-set monologue about a high school friend in Texas, “Bubba,” with whom Earle claimed he would ride around “high enough to catch ducks with a rake,” Earle launched into No. 29, a tribute to the friend on LSD.

Copperhead Road, which followed, marked a shift from alternate country to rock in Earle’s style for his third album and it manifested Thursday night in more movement on the frets, faster rhythms and changeups.

“That record did OK, too,” Earle told an enthusiastic crowd, “But somehow I always found some way to f— things up when they were going well.”

Referring to a long battle with substance abuse, Earle noted he had “managed to keep recording after Copperhead Road, but things were looking dark for me.”

Earle related that following a global tour from Australia to the U.S. west coast, he “slipped off the face off the earth for four years” being jailed for possession of a “tenth of a gram of heroin” and sent for rehab in Lewis County, TN.

At the end of his treatment, he wrote Goodbye, a slow, contemplative apology for regrets, which he shared soulfully Thursday night, moving from a big gravelly voice to softer tones on the refrain: “I can’t remember if we said goodbye.”

A few songs later, after switching briefly to the lighter, Keb Mo-like Nashville Blues, Earle revisited the drug abuse theme in a powerful rendition of CCKMP, “Cocaine Cannot Kill My Pain,” with more complex instrumentals and vocal swings.

If the likes of Tom Ames’ Prayer, Ben McCulloch, Guitar Town and Copperhead Road were the ruddy, American beef in the evening’s performance sandwich, City of Immigrants was the pastrami, as Earle introduced the song with a tale of living over an Italian grocery in NYC that was later owned by a Korean.

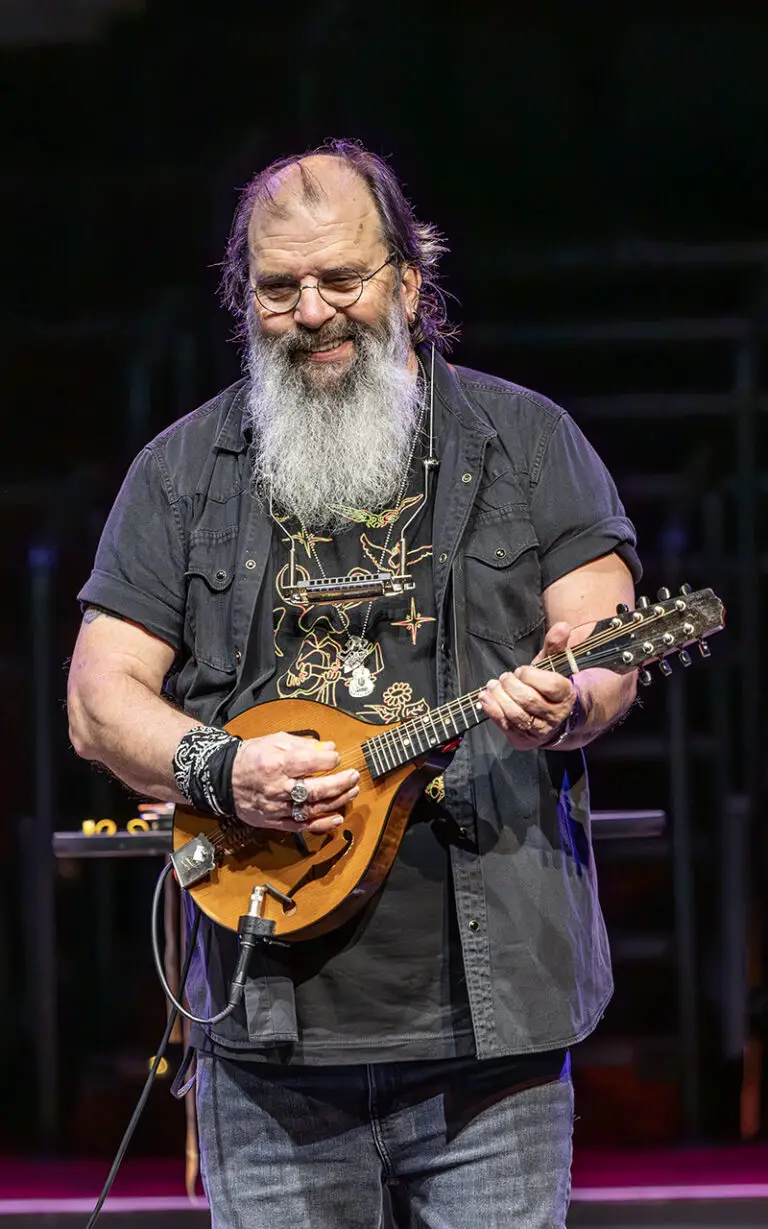

Playing on a bouzouki, a long-necked lute with a metallic sound like mandolin, but lower-pitched, Earle delivered the faster-paced, timely refrain with the audience’s help: “All of us are immigrants. Every daughter. Every son. Everyone is every one.

“All of us are immigrants,” Earle closed. “That’s the truth.”

It was one of several nuanced political comments, including some on gun control, that tinged the performance and topped out in Earle kiddingly ordering the audience to sing along with the chorus of Tell Moses, or “they’ll think you’re Republicans!”

Earle showcased his diversity as an instrumentalist when he switched guitars to share the Eastern-flavored, metallic plinking of “Transcendental Blues,” fourteenth on his set list, and demonstrated some sophisticated picking during a long guitar preamble.

He closed the main part of the show with The Mountain, a throaty sampling of blue grass, which he compared in musicianship to the complexities of bebop, and the haunting It’s About Blood, a narrative about a devastating coal mine explosion, which Earle wrote for a theatre production in New York City. Sung in the persona of Tommy Blue, a victim’s father talking to a reporter after the incident, Earle ended the song by naming each of the miners lost in the tragedy.

Encores included a duet, I’m Not Missing Anything But You, cowritten and sung with Zandi Holum, in bold male/female parts and soft duet harmonies; Tell Moses, written with Shawn Colvin, and The Galway Girl, an Irish ballad on the mandolin, which again demonstrated Earle’s diverse musical ability with faster, choppier rhythms, an occasional foot stomp, “A-aye-As” and hoots in homage to Irish tradition.

Having delivered a hours of music and 20 songs in just his set, Earle closed the show by giving a black bandana he’d worn around his wrist to an audience member.

→ Continue reading at NYS Music